Black Kids Camp, Too...Don't They?: Embracing "Wildness" in Picture Books

My mother was a Girl Scout leader, my father was a Boy Scout leader, and my brother was a Tiger Cub in the Boy Scouts. Practically from the time I could walk, I tagged along with family to scout meetings and events.

My mother was a Girl Scout leader, my father was a Boy Scout leader, and my brother was a Tiger Cub in the Boy Scouts. Practically from the time I could walk, I tagged along with family to scout meetings and events. When I became a Girl Scout, and eventually earned the Gold Award (the highest award in Girl Scouting), I took advantage of every opportunity to get out into the woods. Though an English major, I took almost enough physical education classes at the College of William and Mary to minor in PE. Afterward, to my amazement, I found that outdoor education programs existed that would actually pay me to teach kids in the woods.

My mother was a Girl Scout leader, my father was a Boy Scout leader, and my brother was a Tiger Cub in the Boy Scouts. Practically from the time I could walk, I tagged along with family to scout meetings and events. When I became a Girl Scout, and eventually earned the Gold Award (the highest award in Girl Scouting), I took advantage of every opportunity to get out into the woods. Though an English major, I took almost enough physical education classes at the College of William and Mary to minor in PE. Afterward, to my amazement, I found that outdoor education programs existed that would actually pay me to teach kids in the woods.

This is how I came to spend 1988–1990 working with sixth graders at the Clemmie Gill School of Science and Conservation (SCICON), a residential outdoor education school in Central California near Sequoia National Forest, where for two years I taught outdoor lessons in aquatics, astronomy, animals, conservation, and more. Since I had attended mostly white national Girl Scout events for more than a decade, it came as no surprise that I was the only African American at SCICON and, usually, one of very few people of color at statewide or regional outdoor education gatherings. When I called my mother before deciding to intern at SCICON, she said, “Michelle, what are you doing going into the woods? Black people have been trying to get out of the woods for generations!” A third-generation Girl Scout, I was surprised by her response, but I also knew that she had grown up in the Jim Crow South, where she had to use segregated water fountains and restrooms and where “the woods” were often locales for the lynching of African Americans, and therefore places to be avoided rather than embraced.

Richard Louv argues in Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (2005) that “Well-meaning public school systems, media, and parents are effectively scaring children straight out of the woods and fields.” He posits that because of overzealous parental concerns for children’s safety, the rise of technologies that entertain children and keep them indoors, and the decrease in leisure time for American families as compared with a generation or two ago, children spend little time out in nature, to their detriment. Louv cites a growing body of research that links “mental, physical, and spiritual health” and associates the lack of outdoor time with maladies like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obesity, heart disease, and high blood pressure. While Louv offers a convincing argument for the need for children to spend more time outdoors, the child he writes about (and remembers somewhat nostalgically) is in most cases white and usually middle class. Of course we know that race and socioeconomic status can matter a great deal when addressing the question of what conditions need to be favorable for children and families to spend more time outdoors; and given the limited portrayal of minoritized children having immersive experiences outdoors in children’s picture books, this genre has fallen into the same trap.

* * *

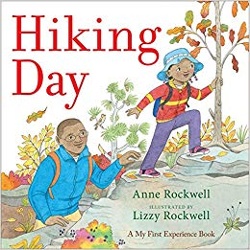

I became acutely aware of this lack when I encountered Anne and Lizzy Rockwell’s 2018 picture book Hiking Day, in which a girl and her family take a day hike in the woods. Along the way, they see a woodpecker, a porcupine, a deer, and some other animals, and though they get a little lost at one point, they spend the day enjoying nature and all it has to offer. What’s so extraordinary about that? Nothing. Or it would have been nothing if this were a white family. But they aren’t. They are African American. I am fifty-three years old and have been studying children’s literature for nearly thirty years — I know a lot of books! But I had read so few books featuring a nature-loving Black kid that Hiking Day felt like something special despite not even being an #OwnVoices picture book; those are even harder to find.

I became acutely aware of this lack when I encountered Anne and Lizzy Rockwell’s 2018 picture book Hiking Day, in which a girl and her family take a day hike in the woods. Along the way, they see a woodpecker, a porcupine, a deer, and some other animals, and though they get a little lost at one point, they spend the day enjoying nature and all it has to offer. What’s so extraordinary about that? Nothing. Or it would have been nothing if this were a white family. But they aren’t. They are African American. I am fifty-three years old and have been studying children’s literature for nearly thirty years — I know a lot of books! But I had read so few books featuring a nature-loving Black kid that Hiking Day felt like something special despite not even being an #OwnVoices picture book; those are even harder to find.

To be sure, many picture books have been published that show Black kids enjoying the outdoors. These include gardening books, such as Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw’s Lola Plants a Garden; and swimming books, including Gaia Cornwall’s Jabari Jumps (an important category since, according to a 2017 study, nearly sixty-four percent of African American children cannot swim, a fact to which I can anecdotally attest as a water safety instructor for over twenty-five years). I have found books about urban play, which often involve Black children finding unlikely critters in the city, as in Mark Pett’s Lizard from the Park; books about farming, like Harvey Potter’s Balloon Farm by Jerdine Nolan and Mark Buehner, in which a Black girl learns to “farm” balloons from a mysterious neighbor; beach stories such as Tom Booth’s Day at the Beach, the tale of a boy who builds amazing sandcastles but realizes that family time might be more important; stories of kids who have a magical relationship with nature, as in Ketch Secor and Higgins Bond’s Lorraine: The Girl Who Sang the Storm Away; and “Goin’ on a Bear Hunt” tales, as in Peter Huggins and Mary Ann Casey’s Thibodeaux and the Fish, a marvelously illustrated story about a boy who sets out on the Louisiana Bayou to catch Pantagruel, the oldest, wiliest catfish in the swamp.

While all of these books include African American children outdoors, nature is the backdrop but not the point of the stories. Those tales therefore don’t reflect the immersive enjoyment of the woods that I reveled in as a child — an experience I am calling “wildness,” a term I gleaned from J. Drew Lanham’s The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature (2016).Lanham writes: “To be wild is to be colorful, and in the claims of colorfulness there’s an embracing and a self-acceptance…Wildness means living in the unknown.” As a scientist, Lanham’s impulse is to identify everything he sees, but he describes “wildness” as a type of immersion that moves outside of an intellectual understanding of the outdoors; it’s a different kind of knowing. Thus far, I have found only three picture books besides Hiking Day that embrace such wildness: the classic The Snowy Day (though set in the more curated “wild” space of a city) and the more recent We Are Brothers and Where’s Rodney?

While most Horn Book readers know Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day and understand its importance as the first Caldecott winner starring a Black child, it’s also significant for its portrayal of the protagonist having an immersive outdoor experience. In many of the images, as Peter smacks a snow-covered branch, drags a stick, and turns his toes this way and that to make different kinds of tracks, it would be easy for readers to forget he is in the city. On some pages, this outdoor encounter involves other kids; on others, it doesn’t. But it’s clear by the end of the story — when Peter peers out from inside — that he longs to be back out in the snow. The Snowy Day paints a picture of a Black kid immersed in his enjoyment of the outdoors long before other white writers and illustrators of Keats’s time saw a need for this portrayal.

We Are Brothers by Canadian author Yves Nadon and French illustrator Jean Claverie tells a lushly illustrated story of two brothers visiting their family’s summer house in the woods. Every year, the older brother leaps from “the rock” into the water, and this summer it’s the younger brother’s turn. He considers his big brother’s leap a thing of beauty: “He is cat. He is bird. He is fish.” The younger brother carefully climbs to the top of the promontory but then stands there terrified and thinks: “What if I slip? What if I miss? What if I die?” But when he sees his big brother’s expectant gaze, he plucks up the courage to jump: “I am cat…I am bird…I am fish…” a metaphorical transformation reflected in a stunningly evocative illustrative sequence. The 2018 Kirkus review of this book notes: “In choosing to make the protagonists black while never explicitly referring to their race, the author and illustrator enable all young readers to understand and experience the transformative power of nature without resorting to preaching.” Claverie has been criticized for a few somewhat stereotyped images of the boys’ faces, but this is an otherwise splendid picture book, notable for its embrace of wildness.

We Are Brothers by Canadian author Yves Nadon and French illustrator Jean Claverie tells a lushly illustrated story of two brothers visiting their family’s summer house in the woods. Every year, the older brother leaps from “the rock” into the water, and this summer it’s the younger brother’s turn. He considers his big brother’s leap a thing of beauty: “He is cat. He is bird. He is fish.” The younger brother carefully climbs to the top of the promontory but then stands there terrified and thinks: “What if I slip? What if I miss? What if I die?” But when he sees his big brother’s expectant gaze, he plucks up the courage to jump: “I am cat…I am bird…I am fish…” a metaphorical transformation reflected in a stunningly evocative illustrative sequence. The 2018 Kirkus review of this book notes: “In choosing to make the protagonists black while never explicitly referring to their race, the author and illustrator enable all young readers to understand and experience the transformative power of nature without resorting to preaching.” Claverie has been criticized for a few somewhat stereotyped images of the boys’ faces, but this is an otherwise splendid picture book, notable for its embrace of wildness.

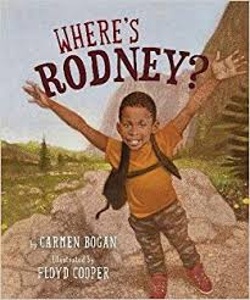

Where’s Rodney? by Carmen Bogan, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, was published by Yosemite Conservancy and Dream On Publishing in 2017, a nod to the hundredth anniversary of the National Park Service (in 2016). Bogan and Cooper portray a common American statistic: an African American boy in the city with a female teacher who does not appear to come from his racial background. Furthermore, she seems not to have established a positive enough relationship with him to figure out why he’s acting out; instead, she threatens him with missing out on the upcoming field trip to “the park” if he continues to misbehave. Since Rodney passes by an unspectacular (city) park regularly, he considers this an idle threat. On the day of the field trip (which he is able to attend), Rodney discovers a park like none he has ever known: a national park. Rodney’s amazement clearly shows in his facial expressions and body language, and in the narrator’s comparisons: “At the park, he was higher. He was lower. He was bigger. He was smaller. He was louder. He was quieter. He was faster. He was slower.” This book’s breathtaking images illustrate the expansiveness of Yosemite and the immersive wildness city kids like Rodney can experience in this national park and others.

Of these few picture books that portray African American children enjoying wild spaces, Where’s Rodney? is the only one with an #OwnVoices author and illustrator. This suggests that much work still needs to be done to provide mirror books (in Rudine Sims Bishop’s words) that are #OwnVoices, for Black children who love the outdoors and want to spend time getting to know more of the secrets nature holds. If we are to avoid raising a new generation of children with “Nature-Deficit Disorder,” then I would suggest that publishers make a positive contribution to these efforts, because #WeNeedDiverseOutdoorBooks.

Of these few picture books that portray African American children enjoying wild spaces, Where’s Rodney? is the only one with an #OwnVoices author and illustrator. This suggests that much work still needs to be done to provide mirror books (in Rudine Sims Bishop’s words) that are #OwnVoices, for Black children who love the outdoors and want to spend time getting to know more of the secrets nature holds. If we are to avoid raising a new generation of children with “Nature-Deficit Disorder,” then I would suggest that publishers make a positive contribution to these efforts, because #WeNeedDiverseOutdoorBooks.

The author would like to thank J. Elizabeth Mills for assistance with this project. See also Michelle H. Martin's May/June 2018 Horn Book Magazine article "Field Notes: Camp Read-a-Rama: Learning to 'Live Books'" and The Atlantic article “Where Is the Black Blueberries for Sal?” by Ashley Fetters (May 2019).

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Alicia Carroll

Thank-you for posting these resources!Posted : Oct 08, 2019 03:45

Michele Prom

As I am seeking to make sure my collection is more diverse, I found this article with its book suggestions helpful. I love the author Donald Crews, and highlight his picture books during the year. I love the story, Big Mamma's, because the children get out of the city and enjoy doing outdoors activities at their grandparents home; swimming and fishing in the pond, drinking water from the well, checking on the chickens, and running past the pear tree where the turkeys roost at night. I enjoy this book because of the connection it makes with family and nature. Michele PromPosted : Sep 23, 2019 01:57