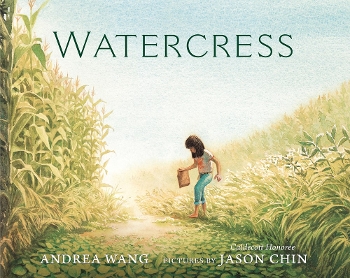

Watercress is a powerful story about how memory flows between generations through the stories we tell and the experiences we share. Andrea Wang’s artfully restrained text serves the story well, evoking both the suppressed memories of the parents’ generation and the complex emotions roiling within their daughter. This gives illustrator Jason Chin a lot of space to work with — and his artwork delivers.

Watercress is a powerful story about how memory flows between generations through the stories we tell and the experiences we share. Andrea Wang’s artfully restrained text serves the story well, evoking both the suppressed memories of the parents’ generation and the complex emotions roiling within their daughter. This gives illustrator Jason Chin a lot of space to work with — and his artwork delivers.

Watercress is a powerful story about how memory flows between generations through the stories we tell and the experiences we share. Andrea Wang’s artfully restrained text serves the story well, evoking both the suppressed memories of the parents’ generation and the complex emotions roiling within their daughter. This gives illustrator Jason Chin a lot of space to work with — and his artwork delivers.

As with any great picture book collaboration, the art and text work hand-in-hand to create a cohesive vision. Chin’s artist’s note in the back matter shows how even his initial choices embody the multicultural themes from Wang’s text. He chose watercolors because “it’s common to both Chinese and western art”; used both Chinese and western brushes; and employed techniques and colors from traditional Chinese painting. These choices infuse each brush stroke with meaning, adding depth to every page.

There is much to process in this book, but I thought the best approach would be to dig into a few of my favorite illustrations.

The book opens with a family’s Pontiac hurtling down a road cutting through American farmland. The bright red car stands out against the green and yellow expanse of crops. Cars are typically symbols of speed and progress, but when this car slows down, we notice rust on the fenders and chipping paint on the exterior. The wear and tear in Chin’s illustrations push back against the iconography of “car as progress,” subtly showing that when we stop and take a closer look, progress isn’t always as smooth as we thought.

This attention to detail pervades the book's illustrations (small tears in the dining room furniture, tattered and mended clothes), and it gives each scene a lived-in weariness that thoughtfully reinforces the story.

Let's highlight another spread. The family has pulled over to the side of the road. (As an aside, if the Caldecott could be awarded based on one spread alone, Watercress would handily win for this one particularly masterful scene.) On the left page, the parents dig into the car’s trunk:

“From the depths of the trunk,

They unearth

A brown paper bag,

Rusty scissors,”

…and the sentence then pauses and hangs there for a moment as the reader’s eye drifts to the right and into a field of tall cornstalks. The corn then transforms into bamboo as we find ourselves in a flashback to a sepia-toned past. On the right-hand page we now see two young children in ragged clothing and the nostalgic ending to the sentence hovering overhead:

“and a longing for

China.”

A technical aspect that makes this spread stand out for me is Chin’s use of the gutter. Typically in a double-page illustration, the book’s gutter is an inconvenience — an unnatural break in the image and the reader’s concentration. Here, Chin uses the gutter as he moves from the present to the past, leading us into a cornfield (which disappears into the dark gutter of the book), only to reemerge seamlessly into a forest of bamboo on the next page. The effect is like a movie dissolving into a flashback. Chin takes what should be a distraction and incorporates it into the visual language of the scene, even weaponizing the gutter to enhance the experience for the reader. It’s a brilliant example of visual storytelling and shows a mastery of the picture book format.

Another notable spread takes place during a flashback to the mother’s childhood in China. On the left-hand page we see a family of four sitting around a small table during a famine, forced to eat “anything we could find.”

The scene repeats on the right-hand page but now with an empty seat where the young brother used to sit. The text simply says, “but it was still not enough.” The words stop short of naming the tragedy (you feel how the brother’s death is still too painful to put into words), so the illustrations carry the burden of showing what happened. Though the family is still seated at the same table, whereas before they were huddled together, now they are emotionally wounded and distant, their trauma carried in their bodies. The father stares blankly into the distance; the mother leans back with her eyes and mouth cinched shut; the sister is hunched over, shoulders slumped and arms hugging her midriff. The family is both together and alone, bound by a grief that is also pushing them apart. Other environmental details accentuate the tragic scene: four empty bowls have become three; rain pours down outside, and the plants outside the door, which had previously been lush with leaves, are now bare. You often hear writing advice about the need to “show not tell,” and this spread is a master class in that.

I’ll wrap up with a quick look at a final illustration, which shows the modern-day family in America sitting together around their dining room table. This final scene shows the main character taking in new information about her family’s tragic past and recontextualizing her own experience. Her problems are still real, but new perspective and context leads to a shift in attitude. The girl who had been so resistant to the free roadside watercress now reaches into the serving bowl to help herself. On the right hand page, the text reads:

“Together,

we eat it

all

and make a

new memory of

watercress.”

The page then fades into a quiet off-white, leaving a blank space waiting to be filled with those new memories.

I’ve keyed in on just a few spreads here, but each page of this book deserves to be pored over. Just as the family’s history slowly reveals new layers over time, these illustrations contain subtlety and depth that are revealed through repeated readings. And when it comes to a visual feast like this one, I know that generations of readers (and hopefully this year’s Caldecott committee) will keep returning for multiple helpings of Watercress.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Watercress here.]

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!