2021 Caldecott Medal Acceptance by Michaela Goade

Lingít x’éináx yéi xat duwasáakw Sheit.een, Dleit káa x'éináx ku.aa Michaela Goade. Kiks.ádix xat sitee. Shdéen Hít yóo duwasáakw haa naakahídi. Ax éesh hás Kaagwaantaan. Sheet’káa yéi xat yatee.

In Tlingit my name is Sheit.een, and in English my name is Michaela Goade. I am of the Kiks.ádi clan. Our clan house is called the Steel House. My father’s people are the Kaagwaantaan. I live in Sheet’ká, or what is now known as Sitka, Alaska.

Lingít x’éináx yéi xat duwasáakw Sheit.een, Dleit káa x'éináx ku.aa Michaela Goade. Kiks.ádix xat sitee. Shdéen Hít yóo duwasáakw haa naakahídi. Ax éesh hás Kaagwaantaan. Sheet’káa yéi xat yatee.

In Tlingit my name is Sheit.een, and in English my name is Michaela Goade. I am of the Kiks.ádi clan. Our clan house is called the Steel House. My father’s people are the Kaagwaantaan. I live in Sheet’ká, or what is now known as Sitka, Alaska.

I am speaking to you all from the same lands my ancestors have stewarded since time immemorial, and I am honored to be addressing you.

It is a daunting thing, to be called upon to put into words what I normally choose to communicate through art. There is so much to say, and so much I want to get just right. Over the last couple months as I’ve fretted over this most public of acceptances, I’ve repeatedly asked myself, “Where do I even begin?”

As Tlingit people, our way of life is based upon our relationship to haa aaní, our land. Where we come from, who our ancestors are, which animals we claim kinship with, our foods, our language, stories, cosmology, traditions — it is all intricately tied to the land.

I grew up in Southeast Alaska, the traditional territories of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Nations. It is a labyrinth of over one thousand islands, endless waterways, and wild, rugged coastlines nestled between the mountains of Canada and the Pacific Ocean. It is a place of ethereal and mercurial beauty, abundant in its gifts yet unforgiving in what it occasionally takes. It is a misty, mountainous, temperate rainforest, where sea blends into sky until your childhood memories are a blue-green blur tinged with salt spray. It is rain country, a wonderland dripping in golden moss and lacy lichen. It is home to a dizzying array of flora, fauna, and many animal relatives. It is a kaleidoscope of glaciers and fjords, rivers and waterfalls, lakes, bogs, wetlands, bays, channels, coves, inlets, sounds…I think you get the idea. And as is often the case around these parts, everything has a way of eventually leading to the sea. After all, as Lingít people, we are People of the Tides.

This is the land that anchors us. This is the water that “runs through my veins. / Runs through my people’s veins,” as Carole Lindstrom so eloquently wrote. It is why, when I first read her manuscript for We Are Water Protectors, I got goosebumps. Immediately I thought, “Where do I sign?” I hadn’t yet learned how rare that burst of clarity can be. The language was poetic yet spare, powerful in its message. The space around that text was vast. I could envision stretching out and making myself at home, layering a world that might flow around and within Carole’s story and maybe, just maybe, create something special.

This is the land that anchors us. This is the water that “runs through my veins. / Runs through my people’s veins,” as Carole Lindstrom so eloquently wrote. It is why, when I first read her manuscript for We Are Water Protectors, I got goosebumps. Immediately I thought, “Where do I sign?” I hadn’t yet learned how rare that burst of clarity can be. The language was poetic yet spare, powerful in its message. The space around that text was vast. I could envision stretching out and making myself at home, layering a world that might flow around and within Carole’s story and maybe, just maybe, create something special.

Everything has spirit. We are all connected. Yáa at wooné, respect for all things. Although I didn’t know the particulars, I knew that I wanted the art to sing with that truth. If I could communicate this, if the art could deepen a reader’s understanding of what it means to be in relationship with the land, or nourish the spirit of a future water protector, I thought I could do the story justice.

Still, I didn’t dive in lightly. As I do with every story that crosses my path, I asked myself if I was the right artist for the job. Does my own lived experience resonate with the story? Will I be able to authentically center Indigenous children? Ultimately, will I do harm by taking this story on? These are important questions I’ve learned to ask, at times the hard way. To be Indigenous is to know injustice, erasure, and misrepresentation. Many people assume that to be Native is to belong to a monolith. But there are over five hundred federally recognized Native Nations across our country, and hundreds more beyond that. Each Nation has its own land, language, traditions, history, sovereignty. I’d never presume to know what it’s like to be an Ojibwe woman like Carole or a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation. I wasn’t on the ground in 2016 at the Sacred Stone Camp, opposing construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Additionally, I am Tlingit and also Norwegian, with an extra tangling of Northern European and Japanese roots. This often calls for a heightened sensitivity to the privileges I carry into this work.

However, I do feel that there is a kinship commonly felt between Native peoples, especially where themes of environmental justice and land stewardship are concerned. Before journeying into the story, and unbeknownst to our editor, Mekisha Telfer, Carole and I hopped on the phone. I needed to learn about Carole’s people, the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe, her inspiration, her hopes, and her connection to Standing Rock. Carole emphasized that although her story was in essence a love letter to the Standing Rock Water Protectors, it was truly meant for all.

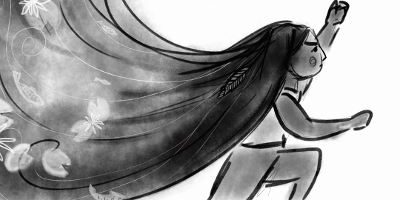

While I chose to root the visual narrative in Carole’s Ojibwe culture, I took this universal message to heart. By leaning into cosmic imagery that carried spirit, emotion, and connection, I hoped the book might speak to all. At the same time, I honored Carole’s people while providing a framework for layers of symbolism. Whether it was the floral motifs paying homage to the traditional Anishinaabe woodland style, the animals that reflected clans or traditional teachings, or the seven ancestors around the fire representing the Seven Fires prophecy, I aimed to deepen the reading experience and thus the representation. My hope was that an Ojibwe reader might one day spot the backs of the turtles popping out of the water and understand that small reference to Turtle Island, or that a water protector might recognize the subtle likeness of Josephine Mandamin, an Anishinaabe elder and one of the founders of the water protectors movement, gazing out from the water. I hoped that Indigenous children everywhere would see our young hero changing into her traditional ribbon skirt as she rallies her people and understand the power of that moment as she embraces tradition while looking toward the future.

I also set out to paint a rich tapestry of contemporary Indigenous peoples’ lives. The 2016 gathering at Standing Rock was historic. Thousands of water protectors, both Native and non-Native, congregated in solidarity at the Sacred Stone Camp. It became the largest intertribal alliance in documented history. I wanted the art to highlight this significant diversity within the unity: different skin colors, a range of ages, and a wide array of traditional regalia and contemporary clothing.

I wanted so badly to make the Standing Rock Water Protectors proud, but I feared a misstep. I worried I might misrepresent, exclude, or unintentionally offend. So, I researched, and then I researched some more. I contemplated how sorrow, frustration, and anger wove together with courage, resiliency, and hope, and how the art might speak to this gravity. I would need to create a visual narrative grounded in tradition and history yet respect different living, thriving cultures. Furthermore, I needed the story to feel timeless, for Standing Rock was not an isolated event. In our country, there is a long, dark legacy of land theft and broken treaties, of colonialism and its systematic attempts to eliminate every remnant of our existence. But there is also a long legacy of Indigenous resistance, of Indigenous-led movements to protect our lands and ways of life. Many are still ongoing: the fights against Coastal GasLink, Keystone XL, Line 3 pipelines, and more.

Today, there are many young folks who are at the forefront of environmental justice issues. They will inherit this world. In all the books I work on, I hope that Indigenous children leave the story feeling seen and celebrated, because they are so often told the opposite in our world. Additionally, it’s vital that non-Native children see these stories centering Native peoples in a multitude of experiences. In this book, it was especially crucial that all children, Native and non-Native alike, came away from the experience feeling autonomous and empowered.

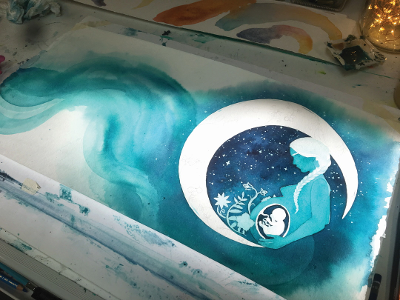

When We Are Water Protectors was on my painting table, my partner and I had the great fortune of living in a tiny cabin tucked away in the forest next to the sea, with an even tinier shed-studio just down the path. I was wildly over the moon about every humpback whale that woke us up with its bubble feeding and smacking tail, every exciting storm that rolled down the channel, every bit of precious rainwater that collected in the large tank below the cabin. It was an entirely magical world, and it informed the making of this book in a very real way. I always knew that I wanted water to be a main character in this book, to encourage readers to ask themselves not what is water, but who. After all, as Carole writes: “Water has its own spirit… / Water is alive.” I attempted to fill the pages with that reverence and respect. I never know what the final art will look like, and that’s part of the fun. Painting becomes a conversation between me and Mother Earth. It becomes another way in which I get to be in relationship with the land, perhaps helping her speak in a way she cannot. It is a way of giving back.

From the beginning, this project often felt like it was much, much bigger than me, an odd feeling to reconcile when you’re working alone in intense isolation, in your pajamas, in a little studio by the sea. It felt so much bigger than me that at times I struggled to take credit or talk about it as a personal achievement. I was, and am, greatly honored to have helped bring this book to life and am proud of what we all created together. It is affirming to know we helped raise awareness of environmental injustice and Indigenous rights. But in some ways it has felt like my role was that of a translator. And now I find myself here, in front of you all, a recipient of the Caldecott Medal, and I am still struggling to speak to these feelings.

To receive this Caldecott Medal is truly an honor, and apart from it being a personal achievement that I am still processing, I am the first Indigenous person and BIPOC woman to receive this award in its eighty-three-year history. Over the last couple of months, I have often been asked what that feels like. The answer is hard to pin down. It’s important to acknowledge this fact, to reflect on the significance. I have so much gratitude for my elders who have helped make this happen by creating opportunities and lifting the next generations up. I am one among many Native bookmakers contributing to a growing canon of Native children’s literature, and that is incredibly encouraging. I am heartened to know that other BIPOC artists and children may see themselves in this recognition and feel proud and affirmed in their path, knowing their stories are powerful and needed. I firmly believe that Indigenous wisdom can help change the world. It is inspiring to feel that the world is listening. This historic honor makes me look to the horizon, to the artists of today and tomorrow, and I am filled with hope knowing that I won’t be the last.

To my fellow awardees, it is a privilege to be in your company. Congratulations! And to the many brilliant books published last year that did not receive recognition, your work matters. I am inspired by you.

Gunalchéesh, Carole. My dear friend, your words were a gift and they inspired me every day. Mekisha, gunalchéesh for your vision and guidance. You saw what this book could be. And to the rest of the Roaring Brook team, thank you for believing in us and providing so much support during these last tumultuous and exciting months.

To my agent and friend, Kirsten Hall, thank you for helping me sail these publishing seas. It has been infinitely smoother and ever more delightful with you by my side. And to Susan Rich, who took a chance on me as my first editor, I am so lucky to call you a friend and mentor.

To the Standing Rock Water Protectors and water protectors everywhere, gunalchéesh for your resilience and courage to fight for Mother Earth in the face of injustice, apathy, and violence. You are fighting for all of us, so that we have a collective future on this planet. I’ll keep working to honor the fight.

And to the 2021 Caldecott committee, aatlein gunalchéesh. Thank you so much. You truly saw everything that went into this book, and it’s still a wonder to think of you all considering it so closely. It’s more than I ever dared to dream. Please know that you have my infinite gratitude.

As the river leads to the ocean, we too steered this book toward the wide, wild world and wished it well. Books find their true purpose in the hands of you, dear readers. Books are magic: they can be a first step toward awareness, they can be a call to action. They can help turn the tide. There is always the hope that the ones we get to work on do some good in the world. You embraced our book so warmly, championed it so passionately, and for that I am grateful. You talked to the children in your life about environmental justice, Indigenous rights and how to be in deeper relationship with the sacred waters and land, and how we are all connected. My dream is that this book will encourage those conversations far into the future and ripple out to sea, growing into wave upon wave of action. What more could this saltwater soul of mine hope for? After all, mni wiconi. Water is life. Gunalchéesh.

Michaela Goade is the winner of the 2021 Caldecott Medal for We Are Water Protectors, written by Carole Lindstrom and published by Roaring Brook, an imprint of Macmillan Children's Publishing Group. Her acceptance speech was delivered at the virtual American Library Association Book Award Celebration, on June 27, 2021. From the July/August 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2021.

Michaela Goade is the winner of the 2021 Caldecott Medal for We Are Water Protectors, written by Carole Lindstrom and published by Roaring Brook, an imprint of Macmillan Children's Publishing Group. Her acceptance speech was delivered at the virtual American Library Association Book Award Celebration, on June 27, 2021. From the July/August 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2021.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Kristy South

Administrative Coordinator, The Horn Book

Phone 888-282-5852 | Fax 614-733-7269

ksouth@juniorlibraryguild.com

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!