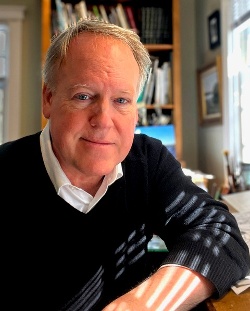

Brian Lies Talks with Roger

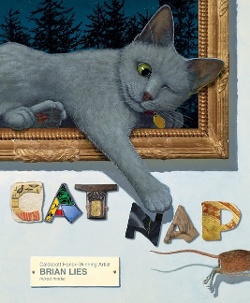

A Cat Nap turns into a fantastical museum tour for the titular feline and for child readers. Brian Lies uses “colored glass, lead, gold leaf, ink, graphite and colored pencil, plaster, wood, goatskin parchment, twine, and clay” to (re)create works of art from different cultures and eras, incorporating Kitten into each one.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

A Cat Nap turns into a fantastical museum tour for the titular feline and for child readers. Brian Lies uses “colored glass, lead, gold leaf, ink, graphite and colored pencil, plaster, wood, goatskin parchment, twine, and clay” to (re)create works of art from different cultures and eras, incorporating Kitten into each one.

Roger Sutton: Let’s talk about Cat Nap. You know, the book made me wonder if as an artist, even if you do primarily one kind of art — like, you only do watercolors, you only do oil paints, you only do sculpture — what skills transfer when you go to use another medium you're not familiar with?

Roger Sutton: Let’s talk about Cat Nap. You know, the book made me wonder if as an artist, even if you do primarily one kind of art — like, you only do watercolors, you only do oil paints, you only do sculpture — what skills transfer when you go to use another medium you're not familiar with?

Brian Lies: Well, I think it depends on life experience, because I'm somebody who's always made things. I've done woodworking. I cook — which is making something from something else. I've always been engaged with materials, and so for me that wasn't really a leap. All the different media I used for Cat Nap were tangential to things that I’ve done before. Maybe not in my books but in my daily life. It was kind of like an amoeba breaking out of its membrane and spilling into something a little bit more. For instance, I had done stained glass in high school. But it was the very standard beginner kind of stained glass, and for this book I had to learn how to truly paint on glass, and that was a different thing because I wanted to use not just cheap paint that is going to flake off, but real vitreous paint. The stuff you bake into the glass. That meant I had to learn the techniques. That meant I had to get a kiln. I took a course through YouTube University on glass painting, had a couple of trial-and-error things in the kiln, and then I had a new technique. I’m very much one of those people who believe that you can learn how to do anything if you set your mind to it.

RS: What inspired you to do a book using so many different techniques?

BL: Well, the whole idea for the story came from our real-life cat Dylan. I know it’s a cliche to say, “My cat did something, so I’m going to write a book about it.” But Dylan disappeared. (And we only have indoor cats.) He couldn’t be found anywhere, and we searched the whole house. The basement, the attic, any kind of crawl space, the dryer — just in case he had managed to jump in and somebody had shut the door on him. We couldn't find him anywhere, and after several worried hours he sauntered into the living room with his whiskers coated with cobwebs. And our thought was, Where the heck have you been? My wife and I talked about it, and we figured he had probably found a wormhole in space and time, and then the cat came back. From there it evolved into the idea that perhaps he had traveled back to ancient Egypt where cats were revered, and so I started thinking, Wait a second, that's a story. Wouldn't it be fun to have a cat who somehow goes back in time to ancient Egypt and interacts with all these different things — papyrus paintings and carvings and little bronze statuettes and things like that? That was what the original story was going to be, him simply going to ancient Egypt. But as I started thinking about that, I really wanted to broaden it. It felt too limited in terms of one culture. I thought about how to make this thing really fun. For me, this was a self-dare, a challenge to myself. How big could I blow this up into all kinds of different source countries and materials? So at this point it's morphed into, Well, this has to be about art in general. Let's make it as crazy as we can. As ambitious as we can. And so that's when I felt that the cat had to be going not just to ancient Egypt but leaping among artworks in a museum somewhere. I live outside of Boston, on the South Shore, so my first thought was the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I absolutely adore the MFA. I went to the Museum School, so at lunchtimes I would hang out at the MFA, and I fell in love with all kinds of pieces of art there. But as I was thinking about this book’s location, I also started thinking about one of my favorite books as a kid, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. As a kid, if you are a reader, you love your favorite books. You bring them in. They are part of you. So part of me is always in the fountain picking up change with those two kids, hanging out at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. And that became my own personal relationship with the Met. From there, obviously, I had to choose pieces of art. I made several research trips to New York and just wandered around the Met with a completely open mind: What about this piece? Could I have Kitten interacting with this? Would it be weird if Kitten dealt with this one? Just many, many hours of wandering through the museum, throwing my heart out into the artworks, thinking, What about this? Well, that’s too grown up. That’s not really child friendly.

BL: Well, the whole idea for the story came from our real-life cat Dylan. I know it’s a cliche to say, “My cat did something, so I’m going to write a book about it.” But Dylan disappeared. (And we only have indoor cats.) He couldn’t be found anywhere, and we searched the whole house. The basement, the attic, any kind of crawl space, the dryer — just in case he had managed to jump in and somebody had shut the door on him. We couldn't find him anywhere, and after several worried hours he sauntered into the living room with his whiskers coated with cobwebs. And our thought was, Where the heck have you been? My wife and I talked about it, and we figured he had probably found a wormhole in space and time, and then the cat came back. From there it evolved into the idea that perhaps he had traveled back to ancient Egypt where cats were revered, and so I started thinking, Wait a second, that's a story. Wouldn't it be fun to have a cat who somehow goes back in time to ancient Egypt and interacts with all these different things — papyrus paintings and carvings and little bronze statuettes and things like that? That was what the original story was going to be, him simply going to ancient Egypt. But as I started thinking about that, I really wanted to broaden it. It felt too limited in terms of one culture. I thought about how to make this thing really fun. For me, this was a self-dare, a challenge to myself. How big could I blow this up into all kinds of different source countries and materials? So at this point it's morphed into, Well, this has to be about art in general. Let's make it as crazy as we can. As ambitious as we can. And so that's when I felt that the cat had to be going not just to ancient Egypt but leaping among artworks in a museum somewhere. I live outside of Boston, on the South Shore, so my first thought was the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I absolutely adore the MFA. I went to the Museum School, so at lunchtimes I would hang out at the MFA, and I fell in love with all kinds of pieces of art there. But as I was thinking about this book’s location, I also started thinking about one of my favorite books as a kid, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. As a kid, if you are a reader, you love your favorite books. You bring them in. They are part of you. So part of me is always in the fountain picking up change with those two kids, hanging out at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. And that became my own personal relationship with the Met. From there, obviously, I had to choose pieces of art. I made several research trips to New York and just wandered around the Met with a completely open mind: What about this piece? Could I have Kitten interacting with this? Would it be weird if Kitten dealt with this one? Just many, many hours of wandering through the museum, throwing my heart out into the artworks, thinking, What about this? Well, that’s too grown up. That’s not really child friendly.

RS: I loved that you didn’t go with any of the usual suspects. It does seem very personal.

BL: Well, that’s the thing. At one point I was thinking, If you want the book to be as relatable to people as much as possible, maybe you should have all the pieces be recognizable ones. I had selected a beautiful painting by Goya where there are all these cats surrounding a little child who has a bird on a string. That one was in the book for a while. Then I thought, No, it’s too familiar. Because then at that point it started to feel more like the book was going to be a parody of the pieces rather than a real appreciation. So I did purposely choose things that most people probably don't know. And part of that also is because of the exploration. For me it was exploration to experience new pieces of art, the ones that you don't see on a T-shirt everywhere. And also my hope that kids who are reading the book may discover something new and feel that art is not just a dead person in a frame on a wall, but it is all these different media, different colors, palettes, and experiences. For me that was really the fun and the challenge — trying to get as many different forms of art into a picture book as possible.

RS: And although all the art is from the Met, it’s not a “let’s visit the museum, kids" kind of book. Do you remember Laurene Krasny Brown and Marc Brown's book about the Metropolitan Museum? It was a how-to on going to an art museum. And I don't see that here at all. I see it as an exploration of the different genres and kinds of art.

BL: I don't like coming to a book from the point of view of a lesson. It’s what my wife and I call a broccoli book. If you are going to dinner at someone’s house and they’re cooking broccoli, you can smell it the second you walk through the door. And for me, a broccoli book is one that is purpose- or lesson-forward. My hope is ultimately that you end up with an engaging story that may have positive things behind it. If people take out of this, “Gosh, I’ve never seen these things at the Met before and I live in New York City, I wonder if I could find them,” if somebody wants to do a scavenger hunt, I think that's marvelous, but that really wasn't the purpose.

RS: Well, you've got that there-and-back-again story, like Where the Wild Things Are, right? The cat leaves home, has adventures, and comes back again.

BL: I'm very drawn to home-adventure-home stories because at their heart, to me, they're very much a child experience. You know, we as kids have our home. We go out and we do exciting things and we come back. Looking back on it, I was thinking about that with this book. A lot of my stories are home-adventure-home stories. My bat books — Bats at the Beach, Bats at the Library — are very much exactly the same thing. I think in my soul I need to feel that we have returned back to the safe and comfortable place that is home.

RS: I agree. Now I want to get into the “old men yelling at cloud” part of the discussion, which is your insistence on creating all the art by hand. That there was no computer manipulation. No AI used in creating this. Yeah, it bothers me too.

BL: AI?

RS: Yep.

BL: The six-fingered kid holding a fox made out of matchsticks and the caption saying, “Nobody has congratulated my six-year-old nephew for making this beautiful piece.” And all the people who go, “Oh my gosh, he’s so talented!” They don’t realize that the kid has got six fingers on each hand. To me, authenticity is really important. And it’s too easy somehow to do things on a computer. I haven’t exactly figured out all my feelings about this yet. I think that’s something a lot of us are struggling with right now. But why is something made by hand valued more than something made by computer? One of the analogies I’ve thought about is a magician; watching a magician do amazing tricks. We can even see a video of a magician and say, “That’s incredible. How did she do that?” Magic is the fact that we know something is impossible, yet we witness it. And the thing is, if you have an AI magician show, who cares? You know that the laws of nature don’t apply when you’re talking about something created on a computer, so it loses all its magic. And I don’t think that we’re going to find a lot of kids running home with a piece of computer-generated art going, “Look at this, look what I made!” to the family.

RS: Or maybe we will, and that’s even more terrifying.

BL: It would have been so much easier to do this book on a computer. But again, to me, the challenge, what made it fun, was the attempt. I do a lot of school visits, and sometimes I’ll ask kids if they’ve ever done something that was really easy and felt super proud. And a couple of kids will raise their hands and then look around to go, “Oh wait, no, that wasn’t the right answer.” And then I’ll say, “Well, wait, if you’ve ever done something that’s really, really hard, raise your hand if you felt pride.” And those hands all shoot up. Kids know the difference. But yeah, again, my interest was in authenticity. And in terms of my own feelings about the book, I care for it so much more knowing that I actually went through the steps to do the things the way they’re supposed to be done.

|

RS: Do you think it would be possible, maybe in a year or two, given how AI is chugging, racing along, that someone could make essentially the book that you made using entirely computer techniques? What would the difference be in the finished output? Which is what a child, of course, sees when they read the book. BL: Well, that’s what worries me about AI. If you have people who don't really understand the difference, I think people will probably accept it. And it'll be perfectly pleasant in its way, and who knows, we may not be able to tell the difference at all. In a picture book, the ultimate thing is the child’s experience with the story. What scares me as somebody who makes things for real is that as long as we're providing kids with good stories and not just pablum, we're not just grinding out thousands of pages of terrible stuff, un-nutritious awful stories, they’ll eat it up and say, “Well, what’s the difference?” If we are creating good stuff with AI, I’m not sure I have an answer. It worries me. For me, authenticity was my strike against the oncoming of AI, doing what my wife calls “Authentic Illustration AI” versus something simply put together by a computer. I did a couple of image prompts for “Russian blue cat on red sofa in late afternoon” and ended up with the most bizarre images in return. Cats with two heads coming out of their shoulders and too many paws and things like that. Those are going to be great to show in school visits this coming year when I am talking about Cat Nap, but I don’t know. The future is an exciting and scary place, and I just hope that we’re able to stay ahead of AI enough that we don’t lose some essential part of our humanity. RS: You're talking about the effort and skill and craft that goes into each one of those paintings that you did, and in the book’s afterword you talk about creating stuff as a kid and not being satisfied with it. I remember a discussion I once had with a reviewer. We were looking at a book that was done in a sort of faux-childlike style, and she said to me — and I’ve never forgotten it — “You know, kids hate that they draw like that. They make stick figures and they know it’s not what’s in their head. But they don’t yet have the skill to do something more.” And skill is all over this book. BL: Thank you. That’s one thing I think is important to get across to kids, which is that it’s not about any kind of super genius. People will say, “Oh, you're so talented.” But for me, I'm thinking about the many, many years of not being able to do things the way I saw them in my head, as you said. As a boy, I was profoundly aware of how childlike my stuff was. I would build things and they would fall apart, or I would get done with something and be like, “It kind of has the shape of what I was looking for, but it's so cheesy.” Again, going back to AI, it’s so easy to not put in the work and not actually develop the real skill base. But to me, the exciting part is getting to the point where more and more starts to look like what I had imagined. I didn’t reach that point until my last four or five books, quite honestly. I’m one of those people who's got a severe case of fraud complex, and I’ve got a very, very severe internal editor. So I’m rarely satisfied with anything I’ve created. And I think it goes back to that childhood place of “Oh man, that looks like it was made by a kid.” As a kid, I always wanted to create something that looked like it had been made by an adult, a professional artist. That dissatisfaction has been running through my entire career: “No, it still looks like it was made by me.”

|

|

BL: It's not that I'm trying to emulate any other authors and illustrators in my regular books. I think what has happened over time is a kind of gentling of that internal editor. The first time somebody said to me, “I can tell that was done by you. That looks like a Brian Lies book,” I was like, “Really? What does that mean?” When I’m working with kids, they'll ask me, “How do you develop a style?” My feeling is that a style basically comes when all the emulation boils away. In some ways, it’s what you do naturally because you’ve developed certain habits of working and ways of applying paint, ways of drawing things, angles, and things like that. The stuff you can't get away from and that you repeat over and over again becomes your style. RS: I think what you're saying is that the craft that you learn, the skills that you develop, allow that style to come clear. Is that right? BL: Yeah, I think that's true. I mean, there are things that you do over and over again because you just like the effect. To me, that’s a burst of dopamine. And of course we want that burst of dopamine again and again. So, yeah. You pare away the things that you feel you’re the least successful at and you focus on the things that you think make the strongest image. Ultimately, they all stick together and create that thing that looks like your work. RS: “...that looks like your work.” How would you characterize a Brian Lies book, the look of it? BL: Detail is something I've always come back to, and that's partly because of my love for Richard Scarry's Best Word Book Ever. I always wish when people ask me if I had a favorite book from childhood that I could name something more esoteric. But for me it was Best Word Book Ever because it was the book where I learned to read. It was the book where I realized that those little black squiggles next to all of the objects in the pictures were actually the word of the thing. But also, those images in that book are so full of little things happening. Each image is what I call a fifteen-minute illustration versus a five-second illustration. You can look at it again and again and again and never be entirely sure that you’ve seen everything that’s in it. And I like that, personally, because I find it more interesting. But also, from a reading perspective I think it’s more interesting because it’s more likely that parents are going to want to read that book more than once too. I’ve had lots of parents who’ve talked to me, or written to me, to say, “My kid likes your book.” And that’s really great. And the parent says, “I realized that I’ve read the book eighteen times and it’s only now that I saw that the little bottle in Bats at the Beach says bain de lune (i.e., moon-tan lotion) on it instead of bain de soleil (suntan lotion).” And I think what happens if a book speaks to the adult who's reading it to the child as well, then you’re going to read it more often, but also that transmits an enjoyment to the child, a love of reading to the child. I think it does a better job of turning a kid into a reader. If you have a kid bring a book to the parent and the parent goes, “Oh, lord, not that one again,” the child knows that that's a rejection of sorts. But if an adult says, “Yeah, let's read that,” that means that this is our together time, uncritical. It creates a kind of parental/child “reading equals love” thing that happens. I still have fond memories of leaning into my mother's side as a little boy, a book on her lap, my older sister on the other side, enjoying this experience together. So to me, book equals love. RS: And the same book read over and over again equals love. Which we lose, I think, as we grow older. The pleasures of reading something over and over and over again. Kids really need that, and picture books are perfect for that because it's developing both their language skills and their visual acuity. BL: And if a book has enough in it to survive that repeated experience, that book becomes a safe place and a joyful place as well as whatever adventure is waiting for you inside. I guess I crowd my pictures with things partly because I feel a need to do it and partly because of my childhood memories of the experience. RS: To keep them coming back for more. BL: To keep them coming back for more, but to make it as rich an experience as possible. We've all seen the cliché of the apple-cheeked children and the intolerable story with the finger-wagging lesson behind it. That just doesn't respect children. And it doesn't respect their curiosity or their complexity. I always think of kids as being basically adults with a more limited vocabulary. Because they have extremely rich inner lives if you are willing to take the time to get to know them and to ask them things rather than what a lot of grownups do, which is bend over and coo, “Oh, you’re so big now.” Every kid hates that. I remember my parents had one or two friends who actually talked to me: “Hey, how are you doing? What’s going on in your life?” I respected that so much because they didn’t do the baby talk, the talking down to me. I think it’s really important to respect kids, where they’re coming from, and give them nutrition, not just sugary cereal. RS: It’s not just giving them nutrition, it’s also giving them — here’s a word I never allowed in book reviews — agency in how they approach a book. Too many books today, even if they’re not cooing to children as you describe, are directing children. “This is what I’m about,” says the book. But we don’t know how kids are going to approach a book. I feel like Cat Nap allows kids to make their own decisions about what they’re going to find in that story, what they’re going to enjoy. BL: Well, that’s my hope. The goal is to allow as many entry points into a story as possible for a reader. I mean, as you say, if you give somebody a roadmap and there’s only this one way into a story, then there are going to be some people who adhere to it and some people who bounce off of it. In Cat Nap I tried to provide many points of entry. For instance, the question of how Kitten actually moves between the pieces of art. I decided that I wanted there to be a little bit of openness to that, for people to go like, “Well, I don’t know. Is he actually jumping off of the wall of a museum and landing in another piece? Is he scuttling somehow behind the wall into something else?” To me, that doesn’t need to be explained. I think kids will use their own imaginations about that. And is Kitten really chasing a mouse? Or is he not? There’s a bit of vagueness there. I know what I think. But I don’t really want to say, because if I do then I am creating that one single entryway into the story. And again, I think it makes things a little stickier and makes people want to return to things again a little bit more if you don’t answer everything. RS: If you find everything the first time through the book, who wants to look back at it? BL: Exactly. That’s what I meant earlier about a five-second illustration. If you look at it and you know the answer, you move on and you’re satisfied. But if you make things a little mysterious, there is that “Well, am I entirely right? Did I see everything there? Did I get it all?” It does make you want to go back. But I think it’s also just that we love mystery. And, going back to magic tricks, we love being fooled. I think it’s boring to know everything as an absolute equation. If there are various entry points to Cat Nap, that delights me. |

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

And the other thing about creating sort of a near-forgery is that in some ways it brings you closer to the artist who created it. You aren’t having the same experience, because you’re coming from a different era, different background knowledge, and different materials knowledge, but to be making something and feeling like you’re sort of in the same space as the person who originally created it is an almost-inexpressible feeling. It was so engaging to be working on these pieces, whether it was stained glass or gilding, learning how to use gold leaf, things like that. It really brings you more of an appreciation for what actually goes into things, rather than just looking at something and going, “Okay, that’s nifty.” And to me, the appreciation of how something was done has always been a personal obsession. If we go out to dinner, I’ll have a certain look in my eye, and my wife will say, “You’re just about to say, ‘I wonder if I could make this at home.’” And she’s right. Anyway, it’s always been interesting to me, the process and how people accomplish things.

And the other thing about creating sort of a near-forgery is that in some ways it brings you closer to the artist who created it. You aren’t having the same experience, because you’re coming from a different era, different background knowledge, and different materials knowledge, but to be making something and feeling like you’re sort of in the same space as the person who originally created it is an almost-inexpressible feeling. It was so engaging to be working on these pieces, whether it was stained glass or gilding, learning how to use gold leaf, things like that. It really brings you more of an appreciation for what actually goes into things, rather than just looking at something and going, “Okay, that’s nifty.” And to me, the appreciation of how something was done has always been a personal obsession. If we go out to dinner, I’ll have a certain look in my eye, and my wife will say, “You’re just about to say, ‘I wonder if I could make this at home.’” And she’s right. Anyway, it’s always been interesting to me, the process and how people accomplish things.  RS: That's an interesting tell right there though, Brian. “Still looks like it was made by me rather than still looks like it was made…” You want it to look like...what? That it's by somebody else?

RS: That's an interesting tell right there though, Brian. “Still looks like it was made by me rather than still looks like it was made…” You want it to look like...what? That it's by somebody else?

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!