"The Caldecott criteria that first comes to mind for Imogen is Yuko Shimizu’s 'appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme, or concept.'” Shelley Isaacson discusses Yuko Shimizu's illustrations for Imogen: The Life and Work of Imogen Cunningham, written by Elizabeth Partridge.

The refrain “something was missing” drives Elizabeth Partridge’s narrative about her grandmother, photographer Imogen Cunningham, until Imogen discovers photography, specifically the ability to develop her own film — and then, “Nothing was missing.”

The refrain “something was missing” drives Elizabeth Partridge’s narrative about her grandmother, photographer Imogen Cunningham, until Imogen discovers photography, specifically the ability to develop her own film — and then, “Nothing was missing.”

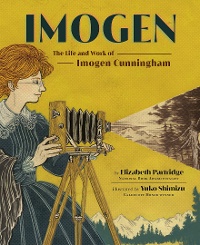

The Caldecott criteria that first comes to mind for Imogen is Yuko Shimizu’s “appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme, or concept.” Shimizu creates illustrations that feel like photographs through her sepia-toned, monochromatic palette and the application of tiny dots that suggest halftones. Although the book is printed using modern reproduction techniques, Shimizu nods to the traditional printing methods and black-and white photography Imogen perfected for much of her career. Of course, the illustrations are not photographs. Rather, as the copyright page notes, they are "created in black ink on watercolor paper, then scanned and colored using Adobe Photoshop." Like Imogen’s photographs, Shimizu’s black-and-white drawings are “developed” in a “photo shop” of sorts with assistive technology, colored digitally, not chemically, but technologically, nonetheless.

The Caldecott criteria also specify that medal-worthy illustrations should demonstrate "delineation of plot, theme, characters, setting, mood or information through the pictures." Most notable is Shimizu’s narrative use of color. The front cover illustration, awash in amber, depicts Imogen and her wooden camera and sets the book in its late-nineteenth/early twentieth-century milieu. In the early page openings, Shimizu punctuates her illustrations with red highlights–the crowns of chickens, a book Imogen’s father reads to her, red watercolors in her paintbox. When Imogen’s father builds the darkroom where she first develops her own photographs, Shimizu fills the room with red light. In this recto illustration, Shimizu contains the darkroom's red glow, framed by the grainy planks and shingles of the woodshed, and she washes Imogen's father in pink, flush from the red light. At the page turn, Partridge writes, “There it was, right in the photographs, all the soft cadence of the poetry, all the beauty, all the feelings she carried deep inside her. Nothing was missing.” Shimizu illuminates this pivotal moment with an explosion of red, coloring the once amber landscape in joyful shades ranging from Imogen’s pink-tinted skin, to the bright red flame of her lantern, to the landscape turned deep red-black. The book’s cohesive design likewise celebrates this climatic moment. When my students discover the narrative possibilities of endpapers, they are often disappointed when they find solid-colored endpapers. This book’s red endpapers, though, beckon readers into Imogen’s darkroom and into her life-changing discoveries. Shimizu further harnesses red to connect Imogen to her father through their shared red hair, a mix of the book’s overall amber hue and the deep red of the darkroom.

Shimizu also delineates Imogen’s insatiable creative impulse. In the final page opening, a crowd gathers around Imogen, her art displayed on an endless maze of gallery walls. Partridge writes that when people asked Imogen which is her favorite photo, she always replied, “The one I’m going to take next.” Here, a row of Imogen's portraits mimics the actual photos that comprise the timeline in the backmatter. Shimizu cuts off the portrait on the edge of the recto, a visual nod, perhaps, to another photo, yet to be taken.

Shimizu does all this while demonstrating "excellence of execution in the artistic technique employed," essential for any Caldecott winner. Shimizu demonstrated her versatility as she recreates Imogen's eight-year-old sketches and her early watercolor paintings; reproduces an article from the May 1901 issue of The Ladies’ Home Journal; and reimagines Imogen’s photographs — each form is distinct yet connected to the book’s cohesive aesthetic. The genius of Shimizu’s art is how she pays homage to Imogen’s work, through well-researched illustrations, while expressing her own creative flair. Just as Imogen’s photographs are artistic interpretations of reality, so are Shimizu’s illustrations artistic interpretation of Imogen’s photographs. Several inspired moments throughout elevate Shimizu’s art. She depicts the moment when Imogen photographs her father, for example, in a page opening that captures the essence of Imogen’s photograph. But she doesn’t merely reproduce the original. On the verso, she superimposes a camera lens over the portrait of Imogen’s father. On the recto, layered on top of the image of Imogen snapping the photograph, are the wing-like hands from another of Imogen’s photos, “Hands with Aloe Plicatilis, 1960.” Readers can see the actual photographs in the backmatter and appreciate Imogen’s photographic talents, and they can marvel at Shimizu’s creative interpretations that invite them to ponder photography as art.

Importantly, Shimizu demonstrates “excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience,” a Caldecott criteria important for all medal-worthy books, but perhaps especially for nonfiction books, often unfortunately presumed less interesting to children. Throughout the book, Shimizu renders the love shared between Imogen and her father palpable — when he gazes into her newborn eyes, when they share an embrace while reading a book, when they squeeze a closed-eyes hug when he gives Imogen her first paint set, and in the penultimate page opening when she shoots her father’s portrait. Partridge writes, and Shimizu illuminates, that Imogen’s life’s work is rooted in love.

Shimizu also invites the child reader to imagine themself in the story, as Imogen. When Imogen reads about “the Foremost Women Photographers of America,” the reader’s hands overlap with Imogen’s as they both examine the newspaper. When Imogen takes her first photograph, and Partridge writes, “Click went the shutter as she captured the image,” Shimizu manipulates the viewer’s perspective so that they gaze directly at Imogen and at the triangular projection from the camera lens that represents the captured image, beyond the scene depicted on the page opening. When Imogen’s father builds the darkroom, the reader shares Imogen’s point of view, and her curiosity, from outside the darkroom peering in. At the page turn, the reader shares her delight, too, at the results of her developed images.

There’s nothing missing from Imogen: The Life and Work of Imogen Cunningham. Except perhaps, a gold sticker.

[Read The Horn Book Magazine review of Imogen]

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!