Caterpillar Man: Remembering Eric Carle

The news of Eric Carle’s (1929–2021) death last May sparked a worldwide outpouring of affection from four generations of readers who were moved to recall the joy his books had given them over the years.

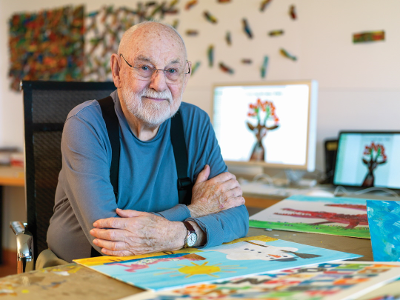

The artist in his studio, circa 2015.

Photo (c) The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

The news of Eric Carle’s (1929–2021) death last May sparked a worldwide outpouring of affection from four generations of readers who were moved to recall the joy his books had given them over the years. Eric always seemed a little puzzled by the outsized success of his picture books and would sometimes quote a sardonic old German proverb — “The dumbest peasant grows the biggest potatoes” — by way of suggesting that perhaps sheer luck had had something to do with it. In more reflective moments, he attributed the popularity of his best-known picture book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, to the fact that children everywhere seemed to find the same message of hope in its story. Paraphrasing that message, he said: “You — little insignificant caterpillar — can grow up into a beautiful butterfly and fly into the world with your talent.”

When his longtime editor Ann Beneduce was asked to explain the Eric Carle phenomenon, she pointed first to the originality of his art and then to Eric’s deep concern for the “emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual growth of children.” As she noted, “That seems like a heavy burden to deliver in a simple picture book, but that is what makes his books so distinctive.” Like Maria Montessori, Eric knew that “play is the work of the child.” He saw the picture book as a kind of playground for learning, and he approached his work as an artist and storyteller with a rare talent for meeting children at eye level on the page.

Eric belonged to the postwar generation of graphic artists who believed that harmonious design had an important role to play in people’s everyday lives — a life-enhancing role with the potential to elevate and inspire, and perhaps even to increase the chances for a more peaceful world. The International Youth Library, IBBY, and the Bologna Children’s Book Fair all had their origins in this hopeful impulse and movement. Among Eric’s design-world mentors and peers were Bruno Munari, Leo Lionni, Dick Bruna, Ivan Chermayeff, and Paul Rand. Like them, Eric embraced the ideal of pithy, smart, deceptively simple graphics as a worthy contribution to the postwar effort to reassert democratic values and establish a common visual language with which to unite people across generations and cultures. With their concern for the future, it is no wonder that each of these great innovators embraced the picture book as an art form.

Eric thought of art and nature as twin realities: art was alive and nature endlessly expressive. He traced his love of nature to the field and woodland walks he took with his father as a child, first in upstate New York, where he was born, and later in Germany, where he was raised and educated. The elder Erich Carle would spot a ladybug or a snake or spider on the ground, take it in hand, and tell his son a story about it. The creature was never detained for long and was handled with the same sense of wonder and respect that Eric later conveyed in his picture books. Often the animal subjects he chose for his books were not the obvious ones but rather creatures that others might easily overlook or, as in the case of the “very busy spider,” misjudge as a nuisance or even a threat. Eric loved these animals for their own sake but also for the ways in which they and humans resemble one another. A sloth is a slowpoke, and so are many of us. A spider has work to do, just like most first- and second-grade schoolchildren.

Eric’s introduction to art happened to him as a five-year-old, in a sun-splashed kindergarten classroom in Syracuse, New York. It was there that a kindly and perceptive teacher gave him his first brushes and paints, praised all his efforts, and privately urged his mother to nurture her young son’s talent. Not long after that, in a first-grade schoolroom in Stuttgart, Germany, Eric came face to face with a very different idea of education — one based on strict discipline, rote learning, and callous indifference to the child’s point of view. It was enough, he later recalled, to turn him off to learning for the next ten years. “Could it be,” he wondered, looking back decades later, “that my cheerful caterpillars, ladybugs, roosters, and spiders have been created to paint over, or even scratch out” those bad memories of stifled creativity and education gone terribly wrong?

He often told a story from his German grade-school years about the day when his art teacher, Herr Krauss, invited Eric into his home and, in direct defiance of the law, showed him reproductions of Expressionist artworks like the ones the Nazi regime had banned as “degenerate.” Eric remained grateful to that teacher for having risked his life for his student’s benefit, and for having opened young Eric’s eyes wide at such a formative time.

At the Academy of Art and Design in Stuttgart, Eric received a rigorous graphic design education. His professor Ernst Schneidler was famously astute about sizing up his students’ talents and soon had Eric pegged as a poster artist. Among Schneidler’s goals was to teach his students not to be precious about their work; with that in mind he required them each to produce a collage in class every day as a kind of five-finger exercise and then, after he had commented on it, to tear their work up and toss it in the trash. The important thing, this exercise was meant to convey, was to do your best work, not rest on your laurels, and keep pushing forward.

Schneidler introduced Eric to his lifelong practice of hand-painting sheets of tissue paper. Papers like these were useful for the daily collage assignments, and Eric found that preparing a new batch was an intensely pleasurable experience — a meditation of sorts and a chance to play freely with color and pattern. Years later, his caterpillar, firefly, and other characters emerged from bits and pieces of these papers. Some hand-painted sheets became the endpapers of his picture books; others became gifts. Occasionally a friend would receive an envelope in the mail. When the envelope was opened, out would pour a radiant Eric Carle rainbow of tissue paper remnants. Eric regarded his hoard of papers as a kind of a treasure and stored them by color in a massive bank of flat files in his studio. If another caterpillar leg or firefly wing was needed, he always knew where to go for it.

Eric was not all idealism, of course. When he returned to the U.S. in 1952, it was with hopes of finding the financial security that had eluded his parents, and he began his professional life in New York as a commercial artist, with pharmaceutical advertising as his specialty. From this sales-oriented work he learned invaluable lessons about branding that later carried over to his picture books, which he designed to resemble one another and to be instantly recognizable as his. Eric’s spry block-letter signature became a trademark, his caterpillar character an icon recognizable around the globe.

As a high-powered art director, Eric did indeed get his wish for security, but commercial work came to seem less and less artistically rewarding. Then, in his late thirties, a chance encounter with the writer Bill Martin Jr pointed him in a different direction. Not too long after that, Eric was searching at his drawing table for a novel way to alter some blank sheets of paper and reached for a hole puncher. The experiment was enough to suggest an amusing tale about a worm worming its way from page to page in a book. Eric called the story “A Week with Willi Worm” and prepared a dummy for Ann Beneduce, then editor in chief of children’s books at World Publishing. Soft-spoken but decisive, Beneduce suggested that readers might have a hard time loving a worm and asked, “How about, say, a caterpillar?” To which Eric replied, “A butterfly!” As the old saying goes, “Well begun is half done” — and with that, The Very Hungry Caterpillar was on its way.

In the 1960s, a picture book with die-cut holes and different-sized pages was a rarity, and the manufacture of such a book posed potentially insurmountable problems. What happened next was an early sign of the coming transformation of children’s book publishing into a global enterprise. Beneduce had been planning to take her vacation in Japan that year. While in Tokyo, she visited a publisher friend who agreed to find a printer there who could do the job. It took a year of experimenting.

The Very Hungry Caterpillar appeared in June of 1969, and the New York Times named it one of the year’s best picture books. But the librarians who led the critical conversation about children’s books in the United States, and who controlled the biggest slice of the American market, did not immediately take to it. Some librarians resisted any picture book with toy-like elements. Some were unsure what to make of a book with so few words and with illustrations that appeared to be so simple.

But Eric’s timing was fortunate in other ways. By the 1960s, a growing number of American parents had taken a college course or two in psychology and were beginning to understand the critical importance of the first years of life to a child’s emotional and intellectual development. Partly in response to this broadly based new public awareness, preschools and day-care centers were popping up everywhere, and Eric’s books were quickly recognized as just right for the children and caregivers they served. His picture books were also embraced by Head Start, a bold government program designed to prepare children in low-income families for school.

* * *

Fast-forward to the late 1990s, when the problem of what to do with the thirty-year archive of his picture-book art and manuscripts began to gnaw at Eric. His initial thought was simply to convert an existing storefront on the main street of Northampton, Massachusetts, near where he lived, into a gallery space for small, rotating exhibitions, and to fill the back room with flat-file storage. In time, however, conversations with local friends, including architect and The Phantom Tollbooth author Norton Juster, prompted Eric and his wife, Bobbie, to think on a larger scale.

A visit to the Chihiro Art Museum in Azumino, Japan, was the turning point. Chihiro Iwasaki was a beloved Japanese picture-book artist of the postwar period. After her death, fans flocked to her home in Tokyo asking to see her paintings. In 1977, a museum in her memory was built on the site, becoming the world’s first museum devoted to children’s book art. Twenty years later, a second, larger museum outpost opened in Azumino. The new museum was designed to blend harmoniously into the surrounding landscape, and to have the broadened mission of exhibiting other illustrators’ artwork, too. The Carles’ visit showed them what might be possible to do in Massachusetts.

In the 1990s, American art museums rarely exhibited children’s book art, and museums for children, which were gaining in popularity, tended to resemble high-tech gaming arcades. Now Eric and Bobbie saw that a picture-book art museum could be a very different kind of children’s museum; that it could also be a center for the appreciation of a global art form; and that it could really be a museum for everybody — just as the best picture books are for everybody.

Now the airy white spaces of Eric’s elegant, open page designs morphed into the soaring white gallery spaces of a museum planned along classic Modernist principles. Eric was convinced that even small children would rise to the occasion and that everyone would come away from the experience with a fuller understanding of an art form that many still undervalued. In addition to the three galleries’ changing exhibitions, visitors would have a variety of other options as well: art and craft projects in the studio; films and live performances in the theater; storyhours in the library; nature walks in the apple orchard or garden just beyond the museum terrace.

Two weeks before the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art opened in November 2002, Eric brought four large sheets of Tyvek into his studio and spread them out flat on the floor. He poured paint into large tubs and, using a janitor’s broom as a brush, improvised four murals meant to suggest his hand-colored papers. The murals were hung side by side on a long white wall in the museum lobby as a foretaste of the galleries’ visual delights. But they were also designed to be seen at night from the approach road leading to the museum. The glass-walled lobby’s interior would be illuminated after dark, and from that distant vantage point the colorful murals and white wall would come together to suggest a page from an Eric Carle picture book. Eric, it seems, had thought of everything.

The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Photo: Paul Shoul. (c) The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

Eric met so many of his fans, and signed so many of their books, that in later years he liked to say that the truly rare copies of The Very Hungry Caterpillar were the ones he had not autographed. He periodically talked about retiring, only to latch onto some irresistible new book idea that once again put retirement on hold. He experimented in other creative directions, too: taking abstract photos of the traffic stripes and pavement cracks he observed during his walks and (on a grander scale) purchasing a house in Florida he did not especially like and immersing himself in its total redesign. He said he could not go out to a restaurant without mentally redesigning the menu or drive on the highway without critiquing the typography of the traffic signs.

Eric’s last major project was a series of angel collages assembled from found objects and inspired by one of his favorite artists, Paul Klee. Until then, Eric had made a point of working with archival materials, but these angel images, which the Carle Museum exhibited in 2020 alongside works by Klee, were to be different. They would degrade over time, he said, and that was what he wanted for them: art returning to a state of nature. It was a beautiful, bittersweet gesture that perfectly expressed Eric’s vision of art and nature entwined.

Some illustrators strive mainly to impress, but Eric cared more about spreading joy. Not that he did not wish his art to be noticed, as can be plainly seen in his audacious use of color, often in surprising combinations. It fascinated him that spiders and many insects, unlike humans, see ultraviolet light, and he may even have been a little bit jealous of them for that, because he would have preferred to see everything. But more than that, he wanted children to feel at ease in the world he imagined for them. Many in his young audience, Eric once observed, “have done collages at home or in their classrooms. In fact, some children have said to me, ‘Oh, I can do that.’” Eric added, “I consider that the highest compliment.”

From the November/December 2021 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!