Children's Books and Contradictions

In March 1888, New York City was in the midst of a legendary blizzard. The city had been caught off-guard, unprepared for a storm so late in the year. The trees were already blooming in Central Park, the birds were singing — and then the unexpected snow. For days, streetcars were silent and New Yorkers sheltered inside.

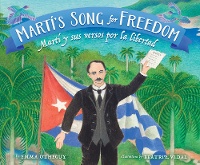

In March 1888, New York City was in the midst of a legendary blizzard. The city had been caught off-guard, unprepared for a storm so late in the year. The trees were already blooming in Central Park, the birds were singing — and then the unexpected snow. For days, streetcars were silent and New Yorkers sheltered inside. I know these details because José Martí, the Cuban poet and independence leader whose life was the subject of my first picture book, Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad (illustrated by Beatriz Vidal, with excerpts from Versos sencillos by José Martí, translated into Spanish by Adriana Domínguez), was living in New York City at the time and wrote about the blizzard. He wrote about the snow in Spanish, for a Latin American audience; he wrote about the halt of city life, the deaths of those who were stranded in the storm, and, with the tough pride of a New Yorker, he wrote about the comeback:

In March 1888, New York City was in the midst of a legendary blizzard. The city had been caught off-guard, unprepared for a storm so late in the year. The trees were already blooming in Central Park, the birds were singing — and then the unexpected snow. For days, streetcars were silent and New Yorkers sheltered inside. I know these details because José Martí, the Cuban poet and independence leader whose life was the subject of my first picture book, Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad (illustrated by Beatriz Vidal, with excerpts from Versos sencillos by José Martí, translated into Spanish by Adriana Domínguez), was living in New York City at the time and wrote about the blizzard. He wrote about the snow in Spanish, for a Latin American audience; he wrote about the halt of city life, the deaths of those who were stranded in the storm, and, with the tough pride of a New Yorker, he wrote about the comeback:

Pero, en cuanto afloja el ataque el enemigo, en cuanto la ventisca desahoga la primera furia, Nueva York, como ofendida, decide sacarse de encima su sudario.

When the enemy’s attack slackened, as soon as the blizzard lost its initial fury, New York, like a survivor offended by the mere mention of its defeat, threw off its shroud.

More than a hundred years later, in March 2020, I was at home in New York City, worrying as worldwide COVID-19 deaths began to climb and our local hospitals were concerned about being overburdened. It was another unexpected twist to an early New York spring, and four months later (as of this writing) we are all left wondering about the future of this city; a city I care deeply about both as my home and because of its literary culture: its publishers, bookstores, schools, and libraries. These institutions have been the basis of my professional life and filled my personal life with literature, but much more importantly, they have provided books to children.

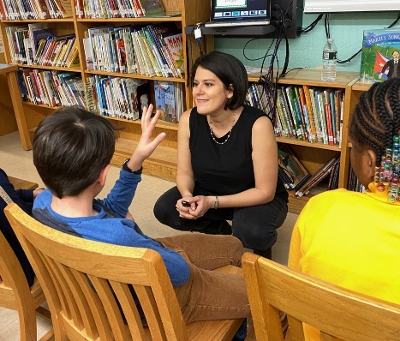

It wasn’t until my first book was published that I understood the degree to which children depend on public institutions such as schools and libraries for access to books. Relatively few children have large book collections at home, least of all new and culturally relevant titles, so most children have books to read only when local, state, and federal governments provide them through schools and libraries (and in some cases, through nonprofits or private foundations). Institutions, whether public or private, are also often responsible for bringing children meaningful literary experiences, including author visits. Personally, I am indebted to the New York Public Library and the Queens Public Library; organizations such as Behind the Book and Meet the Writers; and the teachers and librarians who have advocated for author visits.

I don’t think I have to convince the readers of this publication of why books and author visits are important to students — but suffice it to say that our governments are all too stingy when it comes to these essential educational tools. Budget cuts and shifting concerns have pushed books even lower down the list of priorities. During COVID-19, when many children have lost access to the books they relied on their schools and libraries to provide, and with the economic downturn, their schools and libraries are also losing funds for books and related services. When the public and private institutions that foster and finance literary culture are unable to make books available to kids, these children’s experiences are pushed to the margins of a place where their experiences should be front and center.

* * *

That we don’t prioritize books for children, whether in times of ease or in times of difficulty, is a reflection of the inequality that has plagued New York City (as it plagues other places), and limited the reach of its literary culture now and in the past. José Martí noted stark contrasts between rich and poor in New York City when he lived here during the Gilded Age, and these same extremes are present today. I observe these dynamics during author visits: in an ethnically diverse city like New York, in a city heavily influenced by Latinx and particularly Caribbean culture, it remains a surprise to most students, including those at schools with large Latinx populations, that a Latina might be a book author.

During these assemblies and readings, I try and emphasize the centrality of Latinx cultures and experiences to New York City life: I talk to kids about some of the themes that inspired my middle-grade novel Silver Meadows Summer — my family’s roots in Cuba and my trips to visit grandparents in Puerto Rico; my uncertainty about belonging in the Northeast as someone whose family is from the Caribbean. The students tell me about visiting their own grandparents in the Caribbean and other parts of the world, about the diverse languages they speak at home, and about their own struggles to find a sense of belonging where they are.

When I talk to them about Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad and they learn that José Martí, a figure so strongly associated with Latin America and the Spanish language, was himself a New Yorker, a man who spent a long exile in this, our town, I can feel something about the students’ understanding of New York shifting. They begin to realize that Latin America and the United States are intertwined; that the relationship between New York City and the world, particularly the Caribbean, is the rule and not the exception; and that they belong here, that there is space for them here.

When I talk to them about Martí’s Song for Freedom / Martí y sus versos por la libertad and they learn that José Martí, a figure so strongly associated with Latin America and the Spanish language, was himself a New Yorker, a man who spent a long exile in this, our town, I can feel something about the students’ understanding of New York shifting. They begin to realize that Latin America and the United States are intertwined; that the relationship between New York City and the world, particularly the Caribbean, is the rule and not the exception; and that they belong here, that there is space for them here.

Often after a school visit rich with discussion about the deep ties between Latin America and the United States, kids like to ask me about my favorite bit of poetry by José Martí, who they have now learned was a New Yorker like them. I share these short lines:

Yo vengo de todas partes

Y hacia todas partes voy:

Arte soy entre las artes,

En los montes, monte soy.

I come from every place,

And I’m on the road to everywhere:

I am art amid the arts,

And in the mountain chain, a link.

When I speak to very young children, I have them link their fingers together to represent a chain. Books are a type of link, connecting readers with worlds they otherwise couldn’t access, reminding us of ties we sometimes ignore, like the twining of Latin America and the United States or the interdependence of city and countryside. Schools and libraries are links, places where, for all of our failures as a society, we try to invest in what is good for all of us, connecting readers and resources and bridging the gaps so pernicious and persistent in city life. It may be true that they have done so very imperfectly, without providing enough books or enough diversity of representation to enough children; but in spite of these flaws, these institutions have been bright sources of books for young people.

The COVID-19 crisis has curtailed many kids’ access to books, and now, as New York prepares for its next comeback — the comeback of this century — I hope we will envision a society where children will have the books they need to learn and grow. May it be that New York City, as it did in the days after the Blizzard of 1888, will shake off its shroud, fight the enemies of inequality and segregation, and remain a place where publishing, bookstores, schools, and libraries act as links; a place where literature for children has the public — the whole public — at its heart.

From the September/October 2020 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!