Cynthia Leitich Smith and Rosemary Brosnan Talk with Roger

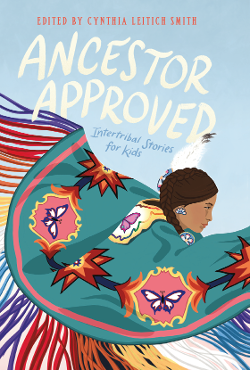

Author (and, just announced, winner of the 2020 Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature!) Cynthia Leitich Smith and veteran editor Rosemary Brosnan have joined forces to launch Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Children’s books devoted to books by and about Native Americans. Rosemary is the vice president and editorial director; Cyn is author/curator, as well as the editor of Ancestor Approved, an anthology of new work by Native authors, and as the author of Sisters of the Neversea, from which Peter Pan may never recover. Oh, just go read it. The list debuts January 2021.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Author (and, just announced, winner of the 2020 Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature!) Cynthia Leitich Smith and veteran editor Rosemary Brosnan have joined forces to launch Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Children’s books devoted to books by and about Native Americans. Rosemary is the vice president and editorial director; Cyn is author/curator, as well as the editor of Ancestor Approved, an anthology of new work by Native authors, and as the author of Sisters of the Neversea, from which Peter Pan may never recover. Oh, just go read it. The list debuts January 2021.

Roger Sutton: I hadn’t realized that you two met on Cyn’s first book, Jingle Dancer. How did that happen?

Cynthia Leitich Smith: Rosemary is my original children’s editor. I’d seen a notice on a children’s writing listserv, which was mostly oriented toward beginners, about an editor who was interested in contemporary stories about Native people. That caught my attention immediately, because one of the challenges at the time was moving past some of the traditional tales and historical fiction to be more inclusive of modern narrative.

Cynthia Leitich Smith: Rosemary is my original children’s editor. I’d seen a notice on a children’s writing listserv, which was mostly oriented toward beginners, about an editor who was interested in contemporary stories about Native people. That caught my attention immediately, because one of the challenges at the time was moving past some of the traditional tales and historical fiction to be more inclusive of modern narrative.

RS: You’re a very faithful editor, Rosemary! Do you remember what it was about that story that made you want to publish it?

Rosemary Brosnan: I do. It was such a long time ago, but I remember having loved it right away. I loved the writing, first of all. And I loved that Cynthia was writing about a contemporary Native girl, and the women around her, and that the women all did different things. There was the cousin who was an attorney — really, we hadn’t seen anything like this in children’s books. It was groundbreaking.

RS: Cyn, what is your recollection of the market at that time for a contemporary Indian book?

CLS: I was living in Chicago at the time, and I came across a couple of Joseph Bruchac’s books at a bookstore — Eagle Song and The Heart of a Chief. I remember taking them off the shelf and cradling them like they were puppies or kittens, very precious living things. It was a revelation. As a child, aside from Buffy Sainte-Marie on Sesame Street, nowhere else in popular culture had I seen contemporary depictions of Native people. As a writer, I was very much in that apprenticeship stage, where I was reading and studying books as mentor texts. I was really taken by Joe’s approach, and thought, Well, if there’s room for this voice, perhaps there’s room for more. So I started researching, and I found that there were some small-press books out there — that was encouraging. I noticed also that there were very few narratives that centered girls or women, so I thought that might be a place where I could make an additional contribution.

RS: How did this square up with your own childhood reading? Did you have a sense as a child of looking for books with Native Americans?

CLS: I tended to avoid books that hinted at any Native content whatsoever. I’ve since tried to unpack that in my mind. At some point as a kid did I come across something that turned me off? I’m genuinely not sure. I don’t have that memory, that linchpin; but I do remember doing it, to the point where my comfort book that I reread every summer was Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond. Right next to it on the shelf was The Sign of the Beaver, and yet I never picked that up. For some reason I just didn’t go there.

RS: Too close, maybe?

CLS: Maybe. I don’t know if it was a lack of trust. I just wasn’t drawn to it for some reason. And I was an avid reader! I actually won a library summer reading award between second and third grade. Growing up, I read all the Newbery and Caldecott books that I could. I actually thought the medals were corporate logos, like IZOD or Gloria Vanderbilt, which were big at the time! I thought, These are published by this Newbery book company, and they do some really good work, so I would look for more of those.

RS: Did you run into Laura Ingalls Wilder in this childhood reading?

CLS: I didn’t read any of the Little House books, but I had seen a handful of the TV episodes. I came to it late, so the only ones I remember were at the Laura-Almanzo stage, which I thought was actually rather romantic.

RS: The hot part.

CLS: Well, romantic. But a lot of it passed me by. I was reading From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler and Judy Blume. I was making other choices.

RS: Rosemary, what led you to actively seek out to publish what we now call diverse books?

RB: As a child I read voraciously, like Cynthia, and both my parents read a lot. My mom was Jewish, and she was very concerned with fairness, equality, and civil rights. I grew up with a strong sense that everyone should be given a chance. And then I married somebody who was from Colombia and we had two kids. But I started publishing diverse books before I even had kids. I published Rita Williams-Garcia’s first book, Blue Tights, and Lyll Becerra de Jenkins’s The Honorable Prison — those were some of my very first titles.

RS: Oh, that’s right. Way Back.

RB: 1988. They came out on the same list. I realized right from the beginning this was something I wanted to do, and that kids should be able to see themselves in books. And then when I had my own sons, who are Colombian and Jewish, they weren’t reflected in any of the books I was finding either, and that wasn’t fair — it goes back to that idea of fairness that I grew up with. I looked into this more, did research, read a lot. I looked at what Phyllis Fogelman had published and was still publishing at Dial at the time. She was a real pioneer in what she was doing, and I thought I want to do that.

RS: This is a devil’s advocate question — why, today in 2020, do we need an imprint devoted to Native American books?

CLS: It’s time to move the conversation forward with Native children’s and young adult literature. For a long time we had mostly books that were centering a non-Native audience. If you were a child of the particular tribe being reflected, you were very cognizant of this forced social studies layer, that the books were skewing a little bit closer to “medicine” than information and entertainment. By moving toward a real conversation and dialogue, we’re able to take that next step — to fully immerse young readers in the perspective, cultures, communities, of various Indigenous peoples, by an author and illustrator who are, for lack of a better term, “Native guides.” Consider the difference between being fully immersed and standing at a distance. I have studied abroad in Paris, studied the French legal system, learned how to speak with people on the street, and carry on a sophisticated argument. I’ve also been to the France Pavilion at Walt Disney World’s Epcot theme park. I’m looking for a little less Epcot and a more pure, authentic experience.

RS: How do you think having an imprint devoted to the theme, specifically, helps?

CLS: By bringing me in as curator of the imprint, I’m able to ask questions that wouldn’t necessarily occur to someone like Rosemary, who is certainly an extended community member — someone who’s been brought into the circle of Native people and our close non-Native friends — versus someone who has lived and walked in it for a long time. There are questions I can ask of Native writers, especially new writers, that they may not have thought of themselves. I can suggest other Native writers for them to read, if they’re trying out a technique or tapping into a particular vibe. Or we can talk through a shared life experience that they’re trying to put on the page. Every writer has that struggle — you have this idealized vision in your head of what you’re trying to say, and then somehow getting it onto the page is something else.

RS: That’s something we’re seeing in general in publishing now, with diverse publishing — you can’t just throw people in. Rosemary, I think we’re roughly the same age — we may share a whole host of assumptions from having worked in children’s books this many years. We take certain things for granted that someone outside the field might not have a clue about. But they’re going to know things that we don’t.

RB: Absolutely, and I would never have dreamed of doing this imprint without Cynthia. Cynthia is a teacher and mentor. She’s finding Native authors and working with them before their books are submitted. She’s part of the community, and she knows so much. I’m really an outsider, who has felt very welcomed into the community, but I don’t have anything near the kind of knowledge that Cynthia has. Her work is the foundation of everything at Heartdrum, and it’s been a dream working with her. I think we’ve signed up twenty-one books already, which are in various stages. We have built something that I feel very proud of. To answer your question about why it’s important to have an imprint — there’s a name on the books, and people know what to look for and what that means. For Native communities, Cynthia’s involvement gives the work credibility. She reviews all of the jacket copy, the catalog copy. We want to make sure we do everything right. It would be all too easy to make a mistake out of ignorance. A well-intentioned mistake, but a mistake nonetheless. From a publishing perspective, having an imprint is really important because you can market the books together. We did an event last week for the California Independent Booksellers Alliance introducing some of the Heartdrum authors — you can do things like that with an imprint that would be much harder if it didn’t have a name.

CLS: It also sends a signal to Native writers. When this idea first came up, one of the questions from different folks in the industry was: Are there enough great writers out there? I was somewhat taken aback by that, because there are, certainly — we’re signing them up, as Rosemary said! But I do believe that a lot of our best Native writers had been self-selecting out of children’s literature, on the assumption that it wasn’t a welcoming place for them. If they wanted to write children’s picture books, they ended up in adult poetry. If they wanted to do something based on their personal life or history, they went into adult memoir. It wasn’t considered a viable path. Whereas now, with this energy, the events around Heartdrum, the fact that it has generated conversation not just within publishing, but within tribal communities, newspapers, radio stations, etc., there is a growing awareness that this is a choice for literary and visual artists, who are already predisposed to writing, to story, to books, and to centering children in the work that they do.

RS: I think one of the most valuable things that the diverse books movement has done — if you look at books by authors who are non-white, or about subjects that are non-white, thirty years ago it was assumed that the “default audience” was white children. That’s something that has really been flipped nowadays. Of course, we still want white children to read The Hate U Give, for example, and they are reading The Hate U Give, but The Hate U Give assumes that its reader can be African American.

CLS: We can trust kids. White kids can make that leap — in some ways more readily than their grownups.

RS: Oh, yeah. I don’t think they notice it as much. How about selling these books? Are you finding different channels beyond trade bookstores, libraries, schools? I’m thinking of when Black independent publishers sold through barbershops. Cyn, are there “Native places” to buy books? Do you have booths at powwows?

CLS: There are book traders at powwows. It’s interesting, actually, that you ask that question, because my short story in our upcoming Ancestor Approved anthology features a couple of kids who are interacting with a powwow book trader. We’re new to connecting the books with readers — we’re more in the process of signing them up, announcing our first titles. But I can say, from acting as an ambassador for books like mine for over twenty years, that a lot of my books moved in those spaces. There are a number of museum gift shops that are particularly interested in books with Native characters and themes. Most of the tribal bookstores or gift stores will also have them. At a number of cultural events, books are featured. They’re integrated through the community, as they would be through the general society, plus.

CLS: There are book traders at powwows. It’s interesting, actually, that you ask that question, because my short story in our upcoming Ancestor Approved anthology features a couple of kids who are interacting with a powwow book trader. We’re new to connecting the books with readers — we’re more in the process of signing them up, announcing our first titles. But I can say, from acting as an ambassador for books like mine for over twenty years, that a lot of my books moved in those spaces. There are a number of museum gift shops that are particularly interested in books with Native characters and themes. Most of the tribal bookstores or gift stores will also have them. At a number of cultural events, books are featured. They’re integrated through the community, as they would be through the general society, plus.

RB: We’re hearing from a lot of the independent booksellers that they’re particularly interested, and also, of course, librarians and educators. Everybody wants to know about Heartdrum! There’s been a lot of excitement in-house in the sales and marketing and publicity departments — School and Library did a wonderful brochure — and there’s a lot of effort to get the word out, where maybe five, ten years ago, I don’t know that we could have really imagined doing this. It was a struggle to publish diverse books for many, many years. Rita Williams-Garcia tells the story about how she used to bring her knitting to conferences and would wait for people to come by and ask her to sign a book, and in the meanwhile she would knit and talk to me. This is how it was. Thank goodness things have changed. We still have a long way to go, but the excitement that we’re seeing—the books are great, the authors are great, we’re doing something new — and there’s also something going on in the larger society that’s making room for more authors and more stories.

CLS: And slightly different kinds of stories. Certainly we’re still seeing stories drawn from family history, personal experience, and cultural touchstones, but there used to be conversations — and there still are to an extent, particularly with BIPOC creators — where authors would struggle with: Can I get away with saying this? Will this alienate too much of the mainstream audience? Will the reviewer get it? There was that effort to navigate what’s sometimes called the white gaze. That has started to fall away, and the work is stronger because of it. When you go in with the idea that you’re going to be pulling punches or negotiating a dynamic that doesn’t ultimately serve the story, you’re automatically diluting the work.

RS: Right. You hope you can count on your editor to say, “This might be clear to you, but it’s not going to be clear to the reader.” Because that will come up, right?

CLS: Of course. And we also have to be cognizant that we’re writing for children. What I, myself, am familiar with today is not what I was familiar with when I was twelve years old, and is not necessarily true of any other Native child. The differences between kids who are in Oklahoma being raised in the Muscogee Nation, maybe they’ve been there all their lives — that’s a very different experience from a child who’s a member of the same tribe, but might be from a military family living clear across the country. Even within that narrow range, there’s still a lot of diversity of perspective, familiarity, and touchstones.

RS: How wide or narrow do you see the scope of the imprint’s books? I’m assuming that the author and illustrator need to be Native American — is that correct?

RB: Yes, that’s right. With Jingle Dancer we refreshed the cover in new type and we’re putting it out in paperback; the illustrators are not Native, but we retained the art because it’s really classic. But otherwise, yes, we are using Native illustrators for the covers of the novels, for illustrations in chapter books, for picture books, nonfiction, everything. And we’re building a database of Native illustrators who haven’t done children’s books. I’m lucky to be working with a wonderful design team who is happy to teach people who haven’t done books before how to create a picture book.

RS: Oh, that's great.

RB: That’s a whole other part of the community building we’re doing. The list has a wide scope — picture books, graphic novels, chapter books, fiction for all ages, nonfiction. But we’re really focusing on contemporary books that center Native kids and teens. There are a few exceptions — if something comes in that’s historical that we feel really fits with our mission, we’ll certainly consider it.

RS: What has been the steepest learning curve that each of you brought to this? Cynthia, you’re an author and a teacher, not a publisher. Rosemary, you’re not Native American. What kind of leaps have you each had to make to meet each other, professionally speaking?

CLS: It was interesting for me to discover that each Harper line has a personality, so to speak. With Heartdrum — it’s not only that we’re doing Native books, we’re really focusing on contemporary books, on page-turning reads that kids would gravitate to for fun. The books would all be welcome in the classroom, but that’s not the only reason to put them in a school library. They’re just as much about entertainment, and aimed at a wider range than we’ve traditionally seen in Native-themed children’s literature. As a writer, you tend to think, If the story is good enough, they’ll like it. But you can have a wonderful story that is, for one reason or another, not a fit with the specific conversation Rosemary and I are having under the more global umbrella of Native children’s literature.

RS: Can you unpack that last part of your sentence?

CLS: There could be a wonderful book that goes on to be very successful elsewhere and that I might dearly love personally, but isn’t in keeping with the particular dialogue that we are having at Heartdrum.

RS: Got it. What about you, Rosemary?

RB: I have so much to learn. You know me; I’m a big talker. I feel like here I need to be a big listener. We had a wonderful Native writers’ intensive workshop over four days in August. It was supposed to be in Austin, but it was virtual, and I actually think that was great, because it enabled people from all over to attend. I did a lot of listening. In my one-on-one meetings with writers — I’m always learning from writers, and from Cynthia, all the time. I’m grateful that people have embraced me and been so welcoming, because I feel as though I have a lot to learn, and I’m trying.

RS: Cyn, do you have a last word for us?

CLS: First, thank you. I’m very grateful for your interest and enthusiasm for this topic. We’re hoping that more readers come into our storytelling circle, that they take a look at Heartdrum books and share them with the children in their lives. And also, if they are new to Native topics or the Native literary traditions they’re seeing on the page, that they maybe take a step back, take a deep breath, and say, “Hey, this is something new to me. I’m going to look at this as an opportunity to grow."

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Danni Roundtree

loved this bookPosted : Sep 02, 2021 12:59