Cynthia Levinson and Evan Turk Talk with Roger

Author Cynthia Levinson (The Youngest Marcher; Fault Lines in the Constitution) and illustrator Evan Turk (Grandfather Gandhi; A Thousand Glass Flowers) bring to the picture book page a man who was a hero to both of them, artist-activist Ben Shahn in The People's Painter: How Ben Shahn Fought for Justice with Art.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Author Cynthia Levinson (The Youngest Marcher; Fault Lines in the Constitution) and illustrator Evan Turk (Grandfather Gandhi; A Thousand Glass Flowers) bring to the picture book page a man who was a hero to both of them, artist-activist Ben Shahn in The People's Painter: How Ben Shahn Fought for Justice with Art.

Roger Sutton: Cynthia, this is not your first biography, but it is your first biography of a painter. How did that happen?

Cynthia Levinson: I’ve loved Ben Shahn’s art for decades. Many Jewish people of my vintage are aware of him because of the amount of Jewish-themed artwork he produced — the Hebrew he incorporated into much of his work, the Haggadah he illustrated. A number of years ago, long before I started writing for kids, I met his second wife, Bernarda, and I was quite taken with her. She and I went to the same high school, about forty years apart. Her recollections sat with me when I started writing children’s books. It took me a long time to learn how to write picture books; I started with middle grade, and I find those easier. But I love the challenge of picture books. And when I felt I was ready, then I turned to Ben Shahn.

Cynthia Levinson: I’ve loved Ben Shahn’s art for decades. Many Jewish people of my vintage are aware of him because of the amount of Jewish-themed artwork he produced — the Hebrew he incorporated into much of his work, the Haggadah he illustrated. A number of years ago, long before I started writing for kids, I met his second wife, Bernarda, and I was quite taken with her. She and I went to the same high school, about forty years apart. Her recollections sat with me when I started writing children’s books. It took me a long time to learn how to write picture books; I started with middle grade, and I find those easier. But I love the challenge of picture books. And when I felt I was ready, then I turned to Ben Shahn.

RS: But wait, I thought picture books were “easy.” They’re so short!

CL: “There are hardly any words. What’s the problem?”

RS: There’s a strong theme of social justice in all your books, though, Cynthia, so he certainly fits right in.

CL: Yes, that’s absolutely right. There are many ways to write about many topics. As I say in the back matter for the book, he was an extremely varied artist. He produced in many media and on a number of different topics. But we authors — and perhaps Evan, too, as an illustrator — find certain topics and themes that we’re drawn to. I have to write the ones that call to me. My take on Ben Shahn, as the subtitle says, is his fight for justice with art.

RS: And Evan, how did you get into this project?

Evan Turk: I was contacted by editorial director Emma Ledbetter, who I had known from working on Grandfather Gandhi. I have always loved Ben Shahn’s work — I did a project on him when I was in fifth grade. He’s been in the back of my head for a while. I think a lot of illustrators really look up to Ben’s work. The public at large may not know it as well, but just mention him in a room full of illustrators! So when I read the manuscript, I was very eager to hop onboard. I loved the way that it was written, and the chance to spend more time with Ben’s work was exciting.

CL: And however excited Evan was to join the team, I was probably ten times as excited that he agreed to do it!

RS: Cynthia, what’s it like seeing a picture-book manuscript come to life with somebody else’s pictures? You didn’t know what it was going to look like when you wrote it, right?

RS: Cynthia, what’s it like seeing a picture-book manuscript come to life with somebody else’s pictures? You didn’t know what it was going to look like when you wrote it, right?

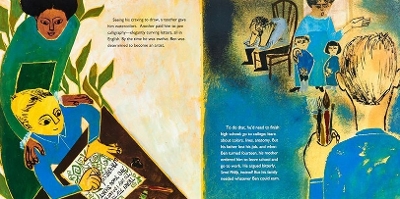

CL: That’s right, I didn’t. Honestly, Roger, I think Evan made this book. My words are only words on the page. Coincidentally, two reviews refer to my writing as “smooth.” I don’t know if I thought of it that way — I struggled over every single word and sentence, and it took me several years to get this as right as I could. But as soon as I saw Evan’s artwork, the whole book just came to life for me, as an experience for readers. Another review said something like “the perfect melding of politics and art,” and I think that’s right. Both the writing and the artwork convey Ben as a political artist. Every time I go through the book, I find more to love about Evan’s art. He and I are doing a launch together on April 28, and we’re going to ask each other questions. There’s so much I’d like to know about what I see in his illustrations — the sort of echoing of Hebrew calligraphy, in the shapes of the leaves, for instance; the way he incorporated Ben’s artwork in places, such as the Sacco and Vanzetti series. The triptych of the family arriving in New York that Evan so brilliantly conveyed in a wordless spread that I didn’t even have in my mind — I just love that spread, because it conveys so much about the immigrant experience. The startling and evocative portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., which I assume you pulled from the Time magazine cover — it’s so much like that portrait, but your own work. What first struck me when I saw the illustrations was that they’re disorienting. The collages, the juxtapositions of people, various points of view, even within one illustration. It matches the disorientation of the times that Ben lived through and responded to. It made the most perfect connection. I love that. And then there’s also the thing about the eyes and the hands...but I should stop talking and let Evan have a turn.

RS: Evan, can you sketch out for us your process of putting these pictures together?

ET: Thank you, Cynthia, for all the wonderful things you said about the artwork. For me, it always starts with the text and the author. Cynthia first had to find that thread, the larger story that she wanted to tell. Usually when I get a manuscript I like to do my own independent research to find my own way into the story. So I started reading about Ben and looking at more of his artwork. There’s the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the Jewish Museum on the Upper East Side. One of the things that really struck me, which related a lot to the way Cynthia had created the story, was his focus on letters and on writing. You could see how much the shapes of Hebrew letters influenced him, and when he had to learn a whole new alphabet, how the shape of the English letters influenced him, as an apprentice lithographer. So, that was one of the things I decided to do in the illustrations. Being a picture-book illustrator — you can only have so many words in a picture book, but in the illustrations, you can have as many different threads going on as you want. A reader can keep looking at them over and over again and notice new things as they go through. For me, it was about finding this way into Ben’s story through the research, but also figuring out what it was that I loved so much about his work, and how to put that into my own illustrations in a way that would make kids excited to learn about him. I think they will be, because even though he addresses death and a lot of heavy subjects, there’s always a lightness and a sense of humor that makes him really approachable.

RS: There’s also a lot of storytelling in his pictures, don’t you think?

CL: That’s another one of the threads, about how Ben wanted to tell stories through his artwork, despite his fuddy-duddy teachers.

RS: Picture-book biography — there are hundreds now. In the past twenty years, it has become a durable subgenre of both biography and picture book. Picture books about artists are a big part of that. Evan, how do you make pictures about an artist without copying that artist, but at the same time, conveying your own excitement about that artist’s work?

ET: No matter how much you try to copy an artist, the difference between that artist and whatever you produce is your own personality. I never felt the pressure to emulate his work, so much as tell a story visually about what his work is like. I’m working on another book right now, a biography of David Hockney, who has also influenced my art. I’ve looked at his and Ben’s art dozens of times; in that way, they’re already a part of my artwork. So it’s less a process of figuring out what the line was between my art and theirs, and more just letting myself relax a little and be like, “It’s all right if this looks like Ben Shahn’s work.” Sometimes there’s almost more of a pressure — I don’t want to look too much like one of my influences, but those books give a little room to say, “I’m going to draw that hand exactly the way that Ben Shahn would have drawn that hand."

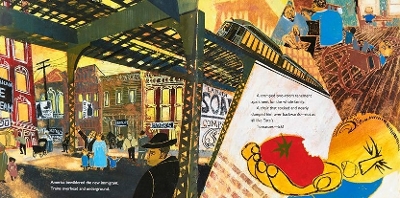

RS: I’m looking at the spread where on the left-hand side the text begins, “For this job, instead of painting on canvas, Ben borrowed a camera.” And then on the right side you see “Young cotton pickers in Arkansas. Impoverished families in Mississippi.” You’ve got this beautiful river of images that goes across the spread, starting with colorful paintings, and then paintings that are in black and white to resemble photographs. Who and how is the decision made for this kind of design?

ET: With this one and the preceding spread, I knew the text was covering a lot of ground in terms of what kind of work he was doing. Ben did several murals that had a montage-like effect, so I wanted to use that type of a design for these spreads. Because I wanted it to feel like he was traveling around the country, going to different places, I used that river shape that you’re mentioning to feel like a journey, with all those different snapshots then coming through.

RS: It’s quite brilliant, I have to say. You’ve made a book that to me doesn’t seem to have a distinct author and illustrator. The book seems so unified. How does that happen? Is that the mystery?

CL: It brings tears to my eyes to think that’s the case.

ET: That’s a great compliment, yeah.

RS: How does a book designer work with a book like this?

ET: I usually do a lot of collaboration with the art director, particularly in the sketch phase. I’ll submit rough sketches of how I think it will be laid out, and I’ll work back and forth with the art director, and they’ll give me suggestions of how it might flow better, or maybe say this page is feeling a little cramped; should we turn this into two spreads? We kind of work back and forth at the sketch stage to make sure that the storytelling is coming across. I did a lot of back and forth with this book, really working to make sure the story was being told. Cynthia mentioned the spread of Ben coming to New York. In the text he was leaving Lithuania, and then the next part of the text was him getting used to his new neighborhood. I talked with art director Pamela Notarantonio, and I think we talked with Cynthia as well, to figure out if we could do a wordless spread to show him arriving at Ellis Island where his family is reunited. So that was a case of, “Okay, maybe we need another spread in here to allow the pacing to make room for his immigration story."

RS: Cynthia, at that stage do you feel like you can just kind of relax, because it’s out of your hands, and you’re just offering opinions?

CL: When I get the advanced reader copies, I can’t read them. In fact, I can’t open a book once it’s between covers for weeks sometimes. And then when I do, I keep wanting to rewrite. There are sentences where I think, “Oh no, I should have used a different verb there.” So, no, I don’t feel relaxed at all. There’s not only the anxiety about how a book is going to be received. There’s also the thought of this sort of thing, being able to talk to you, Roger. Just before we got on the phone I made a video for the Los Angeles Book Festival, which is great fun, but the technicalities of that — I’m a total novice at making videos. Evan, I love the video you made for the American Library Association. For me, it’s anxiety-provoking, and then it gets to the point of exhilaration. “Okay, I can own this.” And also, it’s a great reminder of the team effort in producing a book like this and seeing it all come together.

RS: If you two had to pick somebody right now to do a book together on next, who would you pick?

ET: It’s not a specific person, but I think it would be interesting to do a book about Jewish papercutters, because that was something I wanted to incorporate in the illustrations but it didn’t really fit in. So if Cynthia ever wants to write a book about the tradition of Jewish papercuts, I’d love to illustrate it.

CL: Well, I will certainly think about that one. Roger, we may have to thank you greatly for this question. Of course, Evan, you’re a writer as well, so you could write and illustrate that book. I wouldn’t want to step on your author-toes. But I will certainly take that under consideration. As to another artist collaboration, I know nothing about Leonard Baskin, his personal life, his private life, anything. But I do love his artwork, his Haggadah, as well.

RS: He did some gorgeous children’s books.

CL: Yes, he did.

ET: He was friends with Ben Shahn as well, right?

RS: I smell a book coming up!

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!