Deborah Heiligman Talks with Roger

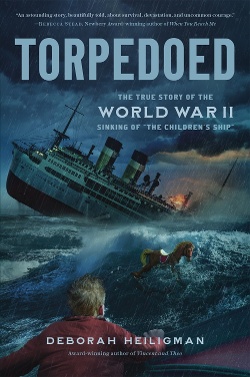

After two biographies about two people each (Charles and Emma [Darwin], Vincent and Theo [van Gogh]), Deborah Heiligman now writes about a cast of one hundred — the precise number of children aboard the SS City of Benares, sunk by a German submarine in 1940 — in Torpedoed: The True Story of the World War II Sinking of "The Children's Ship."

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

After two biographies about two people each (Charles and Emma [Darwin], Vincent and Theo [van Gogh]), Deborah Heiligman now writes about a cast of one hundred — the precise number of children aboard the SS City of Benares, sunk by a German submarine in 1940 — in Torpedoed: The True Story of the World War II Sinking of "The Children's Ship."

Roger Sutton: You said this story began when your editor Laura Godwin showed you a photograph of one of the life jackets worn by children on the City of Benares. What made Laura show that to you?

Deborah Heiligman: A couple of months after I turned in the first draft of Vincent and Theo, Laura said, "Let's have lunch." I had a feeling she was going to ask what I was working on next, so I started brainstorming ideas. I came up with some, but none were very good. Laura is a smart lady, so she didn't like any of the ideas.

Deborah Heiligman: A couple of months after I turned in the first draft of Vincent and Theo, Laura said, "Let's have lunch." I had a feeling she was going to ask what I was working on next, so I started brainstorming ideas. I came up with some, but none were very good. Laura is a smart lady, so she didn't like any of the ideas.

RS: How did she tell you that?

DH: She didn't say it straight out, but nothing made her sit up the way Vincent and Theo and Charles and Emma had. She went, "Oh, you know, um, maybe...but what's the story there?" I thought, okay, that's fine; I've been working really hard on Vincent and Theo, I'll go home and eat bonbons. She didn't like that idea either, I guess, because she said, "A few years ago, I saw an exhibit at the Imperial War Museum, and I can't get this image out of my head." She pulled out her phone and showed me the life jacket photograph and said it was from a ship carrying kids that was torpedoed. My first thought was something like, "It's not my story," but she said, "Why don't you go home and read about it and see what you think?" I took the subway home, opened my computer, typed in City of Benares, and realized, "Oh my God, I'm going to have to write this book."

RS: Why?

DH: It was such an incredible story. I could tell pretty quickly that there were primary sources, interviews from the survivors. I got drawn in, but I was also reluctant, because kids actually died. It was also a different kind of project for me, because it had so many characters. But I kept looking into it. Within a couple of days, a week, I thought, yeah, this is it. I told my agent about it. Laura and I talked about it, and we even talked about my doing it as fiction. She said, "Read War Horse. I'm thinking maybe something like War Horse." So I read War Horse, and I thought, that's great, but why would I do it as fiction? People have done it — Susan Hood's Lifeboat Twelve is a fictionalized version that was only published when I was almost done.

RS: And James Heneghan's Wish Me Luck — I read that some years ago.

DH: I don't mean this in any way against people who wrote about the event as fiction, but the more I read about it, the more I knew I had to write it as nonfiction. There's so much there.

RS: You're very careful in the beginning to say none of this is made up. There's no fictionalization of any kind going on.

DH: Correct. That's always very important to me. So then I wrote a proposal — there's a certain amount of BS in writing a proposal, because you don't really know what's going to happen. I wrote: "...and then I will pull away from one character, make it suspenseful, go to the next character," and in the back of my mind I'm thinking, "How am I going to do that? I have no idea." But it worked out. Writing the proposal was extremely helpful in figuring out what I knew, what I didn't know, what I had to find out. And then the finding stuff out was such a truly amazing journey.

RS: How did you manage to keep that trajectory, working with so many characters and such a tight time frame? You focused on, what, a week?

DH: I wanted the story to be up-close and personal. I wanted to do a lot of zooming in and out — getting really close at certain times, focusing on minute details, and then pulling back. I thought of it as a movie, cinematic.

RS: It does feel like we're going minute by minute, which makes it suspenseful. We're right there with those children in the boat.

DH: That's what I realized as I was working on it.

RS: How did you keep track of what was going on when? Some of it is simultaneous, too.

DH: Nobody was there documenting every minute, so we're not sure everything happened in exactly this order. I had lots of timelines and lots of index cards. My bulletin board for this project is still up, and it has pictures of all the main characters with notes on them. The timeline for lifeboat 12, the one that was lost at sea for eight days, was the hardest. I had primary sources who described what happened in slightly different ways — not disagreeing, exactly, but emphasizing different things and remembering things a little wrong. I really had to piece that one together.

DH: Nobody was there documenting every minute, so we're not sure everything happened in exactly this order. I had lots of timelines and lots of index cards. My bulletin board for this project is still up, and it has pictures of all the main characters with notes on them. The timeline for lifeboat 12, the one that was lost at sea for eight days, was the hardest. I had primary sources who described what happened in slightly different ways — not disagreeing, exactly, but emphasizing different things and remembering things a little wrong. I really had to piece that one together.

RS: At what point did you know that you were going to be so closely focused?

DH: Listening to interviews with the survivors — the Imperial War Museum has some interviews online — and reading memoirs. Just getting really close to the people themselves. I put myself in their shoes — or bare feet — and I was right there with, say, little Jack Keeley, who just kept falling into the water and bouncing back up. Or with Beth Cummings and Bess Walder, the two girls holding onto the overturned lifeboat. The source material was mostly from Bess's point of view, but I also found info from Beth on what it felt like to be holding on and being flung up and down. I knew that's what it had to feel like to the reader because that's how I felt when I was writing it.

RS: Does it feel like there is a definite line between, "Okay, now I'm done researching, and now I'm going to write"?

DH: I wish.

RS: So how do you know? Do you start essentially on the first page?

DH: I start on the first page, but usually that first page completely changes. I always spend more time researching than I probably should. But I didn't know much about World War II. What I knew about World War II was the Holocaust; I learned a lot about the Holocaust growing up, but not about World War II generally. I wanted to immerse myself in World War II, especially the beginning, especially in England. I read books, mostly novels. I watched movies. I wanted to feel what it was like to be a kid or a parent as the war was coming. I wanted to set it up so that readers could understand why parents would send their kids away. I'm researching until the very end, but there is a time when I know I have to start writing, mostly because I have to get it on paper. The book starts with Gussie Grimmond huddling in her family's air raid shelter. When I first read about this story — when I saw that there were five kids from one family who died — that almost stopped me from writing the book, because it was unbearably sad. For the first year and a half or two, I decided I was absolutely not going to write about them. And then I started waking up in the middle of the night with it nagging at me. You know you're going to have to write about those Grimmond kids. How else are you going to write this book? You have to write about them, because the reader's not going to appreciate the survivors unless you show the horrible deaths. You just can't do that.

RS: When you introduce those kids, you do give a little warning. You say something about how the mother wonders how long it will be before she sees them again, and then you say "She couldn't know that it was going to be much worse than that."

DH: Right, because I'm writing for middle-grade kids. But I also had this great primary source material, because the children had written those letters home, so they could tell the story. They could tell me what it was like on the ship. I realized at some point, "Oh my God, not only am I going to write about this family, but I have to start with them. I have to make the reader care about Gussie, so that when she dies, we care."

RS: It almost felt to me like you couldn't bear writing that. There was this sort of clipped "I'm going to announce this and get it over with."

DH: I learned this a little bit when writing the scenes in Charles and Emma where their daughter Annie died: you have to pull back. You don't want to feel the emotion for the reader. You want the reader to be able to feel the emotion. And with this story, it's so horrible. I don't want to give my readers nightmares, so I have to let them enter the story how they want to enter it. That's why I gave a little bit of warning. My friend [children's author] Barb Kerley read an early draft. She wrote in the notes "I love Gussie...Gussie's so great...Uh-oh."

RS: As a reader, you really feel everything pulled out from under you when that happens, because there are other characters you're paying attention to, like the lady who led the lifeboat that took forever to rescue.

DH: Mary Cornish.

RS: I'm thinking, "Is she going to make it? What's going to happen?"

DH: Right. You asked how I know when to start writing, and it's when I have enough facts and the story really takes over.

RS: Have you made a count of how many people are named in the narrative? It's a lot.

DH: It is a lot. When my son read an early draft, he said he was exhausted — it was too hard for him to keep track of the characters. That's really bad news. We decided to include a cast of characters because of that. In moments when I was worried the reader might have lost track of who somebody was, I made sure to give a little bit of information — not so much that the people who were not having trouble would be annoyed. And near the beginning, when I'm talking about the escorts, I say that there were so many children on board they couldn't know who everybody was.

RS: It's interesting how you answered my question — it's as if you thought I couldn't keep track of the characters, and I was going to say the opposite. I felt you were trying to honor as many of those kids as possible.

DH: Well, thank you for saying that. That is something I really tried to do, to honor those who died and those who lived. Of course I can't honor every single person by name within the narrative, but I do at the end. I get very attached to the people I write about. The ones that I couldn't know that well, because they didn't leave interviews or letters, that was a little bit harder, but the ones that I did know, I felt like they were my people. I had to tell their stories. I had no choice.

RS: There is, correctly, no sense of why this person lived and why that person died. The powers at work there seem so random. Some people who tried really hard still died. Some people managed pretty easily through the whole thing. So...wow.

DH: I know. And when you think about the siblings, only one set of siblings in the CORB group survived, Bess and her little brother Louis. So many others lost a sibling. In some cases, it did seem crazily random. I'm still in touch with John Baker, the youngest survivor. We FaceTime once a month. He still can't talk very much about the whole event, because his older brother died. I got very little information from him, and I spent hours with him, in person and on the phone. He's eighty-six — this happened seventy-nine years ago, and he still can't talk about it. Why did Bobby die and he live? Why did little Jack Keeley, who was this slip of a thing, survive having gone into the water twice and being pulled onto a raft? John Baker told me that Jack never got over his little sister, Joyce, dying — she was the one who kept crying because she was homesick for her mother. She didn't make it home. It's heartbreaking.

RS: What did writing this book do to your views about human nature?

DH: It actually improved them. With all the horrible crap that's going on in the world right now — I can barely look at the news headlines — this story was a refuge for me. There are so many stories of not only heroism and courage and bravery, but altruism and community. Michael Rennie, the escort who was going to come home and become a vicar, he dove into the water over and over again to rescue children, and then he died. Or Mary Cornish, who didn't sleep but kept those boys alive singlehandedly by telling them a story and making sure they didn't die in their sleep. People were so amazing, over and over again. When I think about working on this book, it gives me more faith in people, especially people in crisis.

More on Deborah Heiligman from The Horn Book

* "Not-So-Trivial Pursuits: Wooing the Secret Holders" by Deborah Heiligman

* The Book That Changed My Life: "A Lifelong Journey" by Deborah Heiligman

* Vincent and Theo: Deborah Heiligman's 2017 BGHB Nonfiction Award Speech

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

suzy2602@aol.com

This is a very difficult story but one all students should read. It is a perfect example of what did happen during World War Two. I am very proud to say that I am a cousin of Debbie's and she is a true artist. Thank you

Posted : Oct 08, 2019 06:56