2018 School Spending Survey Report

Earlier this season, Robin tackled the definition of a picture book (as contrasted with an illustrated book) and then went on to consider the proliferation of graphic novel elements in picture books.

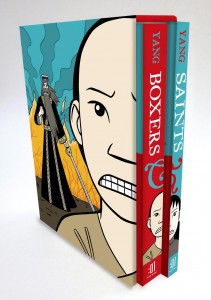

Earlier this season, Robin tackled the definition of a picture book (as contrasted with an illustrated book) and then went on to consider the proliferation of graphic novel elements in picture books. I'd like to revisit these issues, but this time in light of the fact that this year has produced the most amazing crop of graphic novels in recent memory. And for my money the best of the bunch are Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang and March: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. Why shouldn't these books contend for the Caldecott Medal? Because they're not picture books?!? Pshaw!

Earlier this season, Robin tackled the definition of a picture book (as contrasted with an illustrated book) and then went on to consider the proliferation of graphic novel elements in picture books. I'd like to revisit these issues, but this time in light of the fact that this year has produced the most amazing crop of graphic novels in recent memory. And for my money the best of the bunch are Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang and March: Book One by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. Why shouldn't these books contend for the Caldecott Medal? Because they're not picture books?!? Pshaw!Here's the problem with that line of thinking: it's a game of semantics. You don't get to glom on to your favorite definition of what a picture book is, whether it's what That Great Scholar said or This Great Illustrator said; Common Sense; Thirty-two Pages; or even what Most Picture Books Look Like. Rather, you have to go by the very broad definition listed in the Caldecott terms and criteria. It's like an algebra equation: x + 5, let x = 13. It doesn't matter if x in the previous ten equations was always 10. It doesn't matter if 7 is your favorite number. It doesn't matter if 0 makes it easier for you to solve. X=13. Period. End of discussion.

1. A “picture book for children” as distinguished from other books with illustrations, is one that essentially provides the child with a visual experience. A picture book has a collective unity of story line, theme, or concept, developed through the series of pictures of which the book is comprised.

I don't think anybody would seriously argue that the books I mentioned above do not "essentially provide children with a visual experience" or that they don't "have a collective unity developed through the pictures." So, instead people opt for circular reasoning by arguing that they are not "picture books." Doesn't work, folks. Onward.

- Excellence of execution in the artistic technique employed;

- Excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept;

- Appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme or concept;

- Delineation of plot, theme, characters, setting, mood or information through the pictures;

- Excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience.

I don't think we need to spend very much time discussing whether or not Boxers & Saints and March are distinguished in terms of these criteria. Their excellence is pretty self-evident. Some people will quibble with the audience for these books being middle school and junior high, but the Caldecott Medal, like the Newbery Medal, goes up to and includes the age of 14.

It’s true that it's a strong year for conventional picture books, and I couldn't fault the committee if it should recognize nothing but conventional picture books, but I do hope they will at least look outside the box. Because surely the artwork in Boxers & Saints and March is among the most distinguished of the year, and since there is no limitation as to the character of the book, it makes no sense to consider, say, Mr. Wuffles!, Bluebird, and Odd Duck but not Boxers & Saints and March.

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Martha V. Parravano

Jonathan, thank you so much for hosting this indeed-stimulating conversation. You are always welcome in this house!Posted : Dec 18, 2013 07:49

Jonathan Hunt

Bradin, I'm sorry for my late response as I've been busy the past couple of days. I don't feel like this is "my house," and I think think your comments are less welcome than mine. If anything, my viewpoint is the minority one, and thus probably unwelcome in many quarters. I, too, feel that this will be my last response unless somebody introduces a new angle to this discussion. I used to do a graphic novel seminar for BER, and the two-thirds figure came from Gene Yang's humble comics website, but I don't know if that information is still there. I think it's a general estimate, and I think some have a greater visual ration and others less. Matt Phelan's graphic novels, including this year's BLUFFTON, always strike me as essentially visual experiences. I understand that the aesthetics of picture books and graphic novels are different, but I would still call both of them essentially visual experiences, especially in relation to an essentially textual experience (which I would consider the opposite). To my mind, an illustrated book is something like CLEMENTINE AND THE SPRING TRIP which has numerous spot illustrations. The graphic novels, to my mind, are essentially visual experiences compared to CLEMENTINE AND THE SPRING TRIP. I've read your comments several times and I'm still confused by your assertion that graphic novels are not essentially visual experiences, so much in fact that I feel as if I'm arguing with somebody who considers a short film to be an essentially visual experience, but not a full length feature. Yes, they have different aesthetics, but they are both still visual experiences. Can you sense my frustration here? Why I feel like we're playing the semantics game? All of the books in the Caldecott canon are by its own definition "picture books," and I know there are some people would would quibble with things like HUGO CABRET and BILL PEET, and others who may go even further and say things like FABLES are not Picture Books. Ironically, there are graphic novel snobs who would say the same thing: there are graphic novels that are not Sequential Art. Of course, both subsets of these genres of "picture books" may, in fact, be borne out in Caldecott discussion, but they cannot be assumed a priori to be superior. My earlier comments anticipated this argument, but perhaps it was unfair of me to ascribe this notion to you since I don't really know your stance. I do know there are others who feel this way, however, and my comments remain directed at them. The burden of proof that I bear is to prove that BOXERS/SAINTS and/or MARCH are the most distinguished "picture books" not that they are, in fact, picture books or essentially visual experiences because as a hypothetical member of the committee I have the power to bring these titles to the Caldecott table by virtue of nominations. Our hypothetical committee, like Robin's real one, may have engaged in a theoretical discussion of what a picture book is according to the criteria (and, in fact, that is what we are doing here), but this is a purely philosophical discussion, and what we need is to move this discussion from the abstract to the concrete, which is what having these specific examples allows us to do. Thanks to all for a stimulating conversation. It's such a strong year for conventional picture books that I'll be quite delighted with an entire slate of them. But I'd also be pleased with an unconventional picture book, too.Posted : Dec 17, 2013 12:44

KT Horning

This has been a very interesting discussion. But can we talk about the Elmo in the living room? There have been a few references to the number of pages, and Jonathan's question about Mr. Wuffles seems to be designed to get someone to say the only difference between that book and a graphic novel is the number of pages. There. I said it. And now, Jonathan, you can point out that there is nothing in the terms that says a picture book must be a certain number of pages. And you'd be right. But while there is nothing in the Caldecott terms that indicates a picture book must be no more than 48 pages, most people in the children's book field have page length as an unspoken part of their definition of picture book. We can point to all sorts of evidence for this simply by looking at the way libraries and review journals categorize children's books. Look at which books are included in the reviews, for example, that are categorized as picture books. What do they all have in common? Most are 32 or 40 pp. Will you find Mr Wuffles there? Yes. Will you find Bluffton there? No. What is the difference? Page length. Even the oft cited Hugo Cabret was never categorized as a picture book in any of the review media or best of the year listsfor the year it was published. How many libraries or bookstores out there shelve it in their picture books sections? Are there any? And yet a Caldecott Committee was able to interpret the terms in a way that defined Hugo Cabret as a picture book, largely, I think because the terms say nothing about the number of pages. I would wager that page length was never considered necessary to note in the terms because it was thought that everyone had pretty much accepted this part of the definition of picture books. And because, well, while most are 32 pages, some are 24 pages, some 40, some 48. We seem to have gotten it in our heads that this view of what a picture book is is somehow stuffy or dated or limiting. But to my mind, a large part of what makes picture books such an ingenious art form are the constraints, such as page length, within which artists work to create fresh, original, and amazing books, year after year. So my biggest question about your defense of graphic novels is: why? To be provocative? Or because you want your favorite book of the year to have a fair shake at every possible award? Or just because the terms show you can? And to be honest, I could only get worked up about defending graphic novels for consideration if picture books artists had officially run out of ideas, and they were no longer able to delight and surprise us with what they could do within the constraints of a traditional picture book. If the books published in 2013 are any indication, that's not happening any time soon. Until it does, I'll continue speaking out in defense of picture books.Posted : Dec 12, 2013 04:18

Bradin

This is just a quick note to say I appreciate the comments and I'm working on my responses to them. I'm a horribly slow writer, though, and probably won't have them done until this weekend. I'll try to get them out sooner. However, I do want to make one thing clear right away. In no way do I think challenging the status quo is a bad thing, and I would never suggest that "accepted interpretations" be used to institutionalize biases or shut down conversations. But in a disputation the burden of proof must be established, and most often that responsibility lies with the person making the assertion. In other words, if someone makes a claim, especially if it's an extraordinary one, they're expected to back it up. To say the responsibility of providing evidence lies with the opponent is called shifting the burden of proof, and it's a logical fallacy. So, Jonathan made the claim that, according to the Caldecott terms and criteria, graphic novels are picture books. Instead of offering evidence to back up that claim, he left it to his opponents to prove that graphic novels are NOT picture books. The purpose of my original comment was to point out that the burden of proof lies with Jonathan, and it was never intended to suggest there's something wrong with questioning "accepted interpretations" or anything like that.Posted : Dec 12, 2013 06:02

Jonathan Hunt

Bradin, here's a fuller response to some of your points . . . 1. You write, There’s no doubt, graphic novels provide a visual experience, but it’s not essentially a visual experience in the same way it is with picture books." Does it have to be essentially a visual experience in the same way it is with picture books? Can't it just be essentially a visual experience? I think so. I'm not sure your arguments about length or panels hold up very well. MAKE WAY FOR THE DUCKLINGS (76 pages) and THE BIGGEST BEAR (88 pages) defy the length of the standard picture books. Does that make them not-picture books? And as for the panels, you've yet to convince me that MR. WUFFLES is essentially any different from BOXERS/SAINTS. Are they? 2. You also write, "Yes, the graphic novels you mentioned have some collective unity, but these elements aren’t nearly as unified as they are in a picture book." Once again, I'm not sure I agree with you, but still: Do they have to be as unified as a picture book--or can they just be unified? And as for short stories vs. novels, since both of them can win the Newbery Medal, then why shouldn't both picture books and graphic novels win the Caldecott Medal? 3. And still later: "Since you’re making claims that attempt to disrupt the accepted interpretations both of an established artform and the criteria of its highest award, I think the burden of proof lies with you." Accepted interpretations are not necessarily correct interpretations, and I believe ALSC encourages each committee to wrestle with these terms and criteria anew every year. Most committee members, myself included, will come to the table with a preferential bias toward conventional picture books, and some people will not be able to move beyond that bias, but that doesn't mean that it should be institutionalized in the committee process, and used as a way to shut down the conversation. 4. I'm guilty as charged in terms of not defending my choices according to the criteria At least not yet, maybe a follow-up post is in order? I'm not arguing that they should be recognized this year, as much as I'm arguing that they should be considered (which as K.T. mentioned, I cannot ever really know) and that they should be part of our conversation (which I can know, and quite frankly I don't see or hear very much Caldecott buzz for these kinds of books).Posted : Dec 12, 2013 01:19