Duncan Tonatiuh Talks with Roger

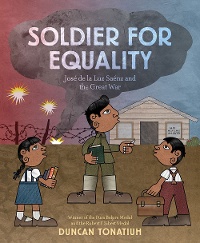

You can spot a picture book by Duncan Tonatiuh from quite a distance, but it's not just his pictures that stand out. Take a look at his unusual subjects, such as José de la Luz Sáenz, a U.S. Army soldier who came back from World War I determined to make life better for his fellow Mexican Americans. Luz's story is told in Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

ABRAMS

You can spot a picture book by Duncan Tonatiuh from quite a distance, but it's not just his pictures that stand out. Take a look at his unusual subjects, such as José de la Luz Sáenz, a U.S. Army soldier who came back from World War I determined to make life better for his fellow Mexican Americans. Luz's story is told in Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War.

You can spot a picture book by Duncan Tonatiuh from quite a distance, but it's not just his pictures that stand out. Take a look at his unusual subjects, such as José de la Luz Sáenz, a U.S. Army soldier who came back from World War I determined to make life better for his fellow Mexican Americans. Luz's story is told in Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War.

Roger Sutton: How did you first find out about Luz?

Duncan Tonatiuh: In 2014, I published Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & Her Family's Fight for Desegregation, about the civil rights case that desegregated schools in California in the 1940s. The book was very well received—people really connected to it. A lot of people didn't know this story.

RS: I didn't! I remember reading that book and having the same sense I do with this new book: "Here's this piece of history that's really important, but I never heard about it."

DT: My editor first told me about the Mendez case, because he knew I'm interested in history and social justice. Then I happened to be at a book festival with Sylvia Mendez, so I got to talk to her. Sometime later I learned about Luz, who helped create the League of United Latin American Citizens after World War I (Emilio Zamora, who translated Luz's diary, first told me about him). One of the people involved in the Mendez case—the dad in the Estrada family—was in the U.S. Army, so that already had me thinking about this idea that even though you might have been serving in the military, your children would still be sent to segregated schools. When I heard about Luz, it seemed like a continuation of the theme.

RS: Well, it's quite a story. Were you a kid who read war stories or enjoyed playing war when you were little, like me?

DT: A little bit, but I was more into superheroes. My older cousin got me interested in comic books when I was about eight or nine, and that's why I started drawing. We would read the X-Men and Spider-Man and try to make up our own little stories.

RS: What effect do you think those comics had on your own work today?

DT: They were my first inspiration. Then I became interested in other things, like political cartoons, anime, and manga. In high school I got really into painting—I wanted to paint like Van Gogh and Egon Schiele. In college I liked graphic novels like Maus and Persepolis, and I wanted to do something like that—something that was visual storytelling, but also dealt with politics and social issues.

RS: Where did you go to college?

DT: The New School, Parsons School of Design and Eugene Lang College—I did a dual degree program. My book Undocumented: A Worker's Fight came about because of my senior project in college. I was volunteering at a workers' center at the time, and decided to focus on some of the people I met there. Some of the people were Mixtec, which is an indigenous group from southern Mexico, and I started studying Mixtec artwork—which has become a big inspiration for my own work. Undocumented folds out like an accordion because that's the way codices, the books that Mixtec people made hundreds of years ago, folded out. So, I started working on that project when I was in college, and the professor really liked it. She was friends with an editor at Abrams, Howard Reeves, and she introduced me to him. I showed him my work, and that eventually led to doing a picture book, and ten years later, we've made nine books together.

RS: Wow, that's terrific. When we're reviewing your books here at The Horn Book, and I've noticed it other places as well, we say something like "inspired by the Mixtec codex" as if we know what we're talking about, and we don't. Can you explain for our readers what that is?

DT: In the Americas, before the Europeans came, there were lots of different civilizations, people like the Aztecs, the Maya, the Inca in South America. And the Mixtecs—there is the modern-day Mixtec indigenous group, but there was also a Mixtec civilization that built pyramids and had their own cities and form of government. And they made books. Most of those books were destroyed during the Spanish conquest because they did not fit in with Christian beliefs, but a few survived. The codices can be read kind of like Egyptian hieroglyphics—they are drawings, but they're also a way of writing. They're very stylized, with figures drawn in profile. The way a hand is drawn, or if the arms or legs are crossed—things have different symbolic meanings. These books are unique, and very beautiful. I was familiar with that kind of art when I was a kid, because I grew up in Mexico and you just see those images around.

RS: There's an interesting tension there, between using this ancient artistic perspective on very twentieth-century stories. How did you hit upon doing that?

DT: When I did that first story—the one that eventually, many years later, became Undocumented—I wanted it to be a modern-day codex of what some of those workers I met were going through. I wanted the style to be reminiscent of codex art, but I didn't want it to be an exact copy. I draw by hand, but then I use Photoshop to digitally collage a lot of textures into the art. There's a kind of duplicity going on, sometimes through the theme, but sometimes through the look of the art.

RS: Do you like having a signature style? Do you ever resent it?

DT: I do like having a signature style. When people see my books they know that they were made by me; they can connect them to my other books. I do want to find ways to evolve a little, to experiment and play around while still retaining some of that essence. But I really like my way of working. Sometimes when kids see the art they'll be like, "Why do they look like that? Why do their ears look like that? Why do their lips look like that?" Then sometimes after someone explains the history, or shows them reference images, they get excited and try to draw in that style themselves. I think it's cool to celebrate that tradition of art and share it with young people nowadays.

RS: Why do the ears look like that?

DT: That's what they look like in some of the codices. When I was first coming up with my style, I would try to draw the people in modern dress—basically I tried to imagine how an artist from five hundred years ago might draw a person of today. I noticed the ears, and how the people are always in profile. I do that, too, in my art—it's fun! When you have a set of parameters for yourself, it forces you to try to be creative. And because the drawings are very stylized, I can break some of the rules of perspective. I'm especially happy when I make an image that you're looking at from above and from the side at the same time—which is something that we cannot do in real life.

RS: Like Picasso—combining those perspectives and showing them at the same time in a single image.

DT: Yeah, and it's something you also see in naive art, art that is made by people who have not had formal training. That's another place where I draw a lot of inspiration for my work.

RS: One thing I thought, looking at the ears, was that for whatever reason, hearing was important to that culture.

DT: Sometimes in the old books they'll have little speech bubbles emphasizing when someone is speaking. That's interesting, too, this idea of suggesting listening with the stylized ear.

RS: And that's another link from the codices to comic art. It's not just a picture sitting there on the page—it's one picture in a narrative sequence, and the idea is to move from one to the next. You've talked a lot about your sociopolitical concerns, being progressive and wanting social change. How do you think books can help?

DT: First of all, by giving an issue visibility, or giving a group of people visibility—which is fortunately being talked about, the need for diversity in children's books. The books that are out there don't necessarily reflect who the children in the United States are. Just giving people more representation—when you do that, two things happen. On the one hand, children of color, Latinx children, different kinds of children—when they see themselves in books, it helps them know that their stories are important, their voices are important, they can feel proud of who they are. And the other piece of it is that for kids who have not had these kinds of experiences—when you encounter through books people who are different from you, you're able to learn about them and get to know them, so that when you meet them in real life, you're less likely to have prejudice against them. You're more likely to understand a little bit of where they're coming from, who they are.

DT: First of all, by giving an issue visibility, or giving a group of people visibility—which is fortunately being talked about, the need for diversity in children's books. The books that are out there don't necessarily reflect who the children in the United States are. Just giving people more representation—when you do that, two things happen. On the one hand, children of color, Latinx children, different kinds of children—when they see themselves in books, it helps them know that their stories are important, their voices are important, they can feel proud of who they are. And the other piece of it is that for kids who have not had these kinds of experiences—when you encounter through books people who are different from you, you're able to learn about them and get to know them, so that when you meet them in real life, you're less likely to have prejudice against them. You're more likely to understand a little bit of where they're coming from, who they are.

RS: You bring an interesting bicultural perspective as a Mexican American. You grew up in Mexico, right? How are your books received in Mexico?

DT: Most of my books have been published in the U.S. first. I have a few books published in Mexico now, but most of my career has been in the U.S. One of the reasons I wanted to do books that talk about the Mexican American experience is because I miss things that were around me growing up—the music, the food, different traditions. Things that I'd taken for granted—I began to see how special they were. And I also came to realize the need for them—there's a huge Latinx population in U.S. schools who really want these books, who want to see themselves reflected in books. And teachers and librarians who want to be able to connect with the children they interact with.

RS: Do Mexican schools have the same tradition of school visits from authors that are so popular here?

DT: I'm currently living in San Miguel, in central Mexico where I grew up, and there's a really good writers' conference here every year. I do a workshop for teenagers, and I've done things for a summer program. I've visited some schools here, and some in Mexico City. There's a good publishing industry in Mexico, but the one in the U.S. is a lot bigger and more robust. There are a lot more books being bought. My thinking is that a book in the U.S. and Mexico costs about the same, but what people earn in Mexico is a lot less than what people earn in the U.S. The books for children being published in Mexico may be more for adults, because they're more precious objects, while the books in the U.S.—you really want to put them in the hands of kids. There are publishers in Mexico that are doing great work celebrating the traditions, the art of Mexico, the history of Mexico, but the industry is much smaller. In the U.S., people print ten or fifteen thousand books for the first run, and in Mexico maybe they print a thousand.

RS: And there are more titles being published here.

DT: Yeah, way more titles.

RS: You said that when you went to college you noticed things about your own heritage that became apparent when you were thousands of miles away from it. What did being in the U.S. do for you when you came back to Mexico? You talked about how being Mexican in the United States meant one thing to you, and I guess I want to know what being an American in Mexico meant to you, coming back.

DT: Sometimes people in the U.S. say, "Oh, I'm not American enough in the U.S., but if I go back to Mexico, I'm not Mexican enough." Maybe that's something with all children of immigrants—you don't necessarily feel fully accepted by society because maybe you don't fit into the mainstream perfectly. I felt a little bit of that in the U.S. when I was younger. But I have family in both places and I’m a citizen of both countries—I have a Mexican passport and a U.S. passport. I've voted in both countries. I pay taxes in both countries. I'm very involved in both places. Currently I feel very much American, but very much Mexican also. I feel lucky for that, because I know it can be a challenge for people to feel welcome. Sometimes when I visit schools I'm invited to talk with parents, and what I say is that you can be a part of the U.S., involved in your community, involved in your school, but that doesn't mean you need to give up your culture, your traditions, where you came from. Quite the opposite. That kind of diversity, that's what's really special about the United States, that there are so many different cultures and so many different languages. Kids shouldn't feel ashamed if they know Spanish. It's a gift. Eating different food at home shouldn't be something to be embarrassed about. That's something special. You can be a citizen or a resident of the United States and at the same time be very proud of where you came from and of your traditions. Those things don't need to be mutually exclusive.

Sponsored by

ABRAMS

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!