Erin Entrada Kelly Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

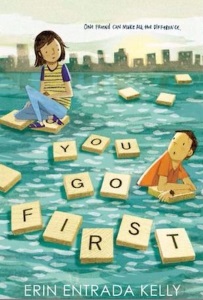

In You Go First, 2018 Newbery medalist [for Hello, Universe] Erin Entrada Kelly probes the lives of two kids, Ben and Charlotte, who only know each other through online Scrabble and the occasional text message. But that, this novel suggests, can be a lot.

In You Go First, 2018 Newbery medalist [for Hello, Universe] Erin Entrada Kelly probes the lives of two kids, Ben and Charlotte, who only know each other through online Scrabble and the occasional text message. But that, this novel suggests, can be a lot.Roger Sutton: How far along were you with You Go First when you won the Newbery Medal?

Erin Entrada Kelly: You Go First came out about a month after the Newbery announcement. It was already done and put to bed by the time the announcement came around.

RS: That must have been a relief.

EEK: It really was, actually! Obviously it worked out well — people don't tend to win the Newbery and say things didn't work out. But yeah, it was great timing. Serendipitous. And even as we speak I have the revisions on my next book [Lalani of the Distant Sea] from my editor Virginia [Duncan]. It'll go on sale on May 7, 2019.

RS: You are very industrious.

EEK: I'm a bit of a workaholic, I guess you could say. People ask me about writer's block, and I actually have the opposite problem. I get overwhelmed. I call it a "writer's storm."

RS: Does that sustain itself, or does it go in fits and starts?

EEK: It'll go for a while, and then I'll exhaust myself, and then I'll recharge like a battery for a couple of days, and then I'll go again. I think of myself as a train going down the tracks. Eventually I run out of steam and I have to stop at the station for a little while. But I like to be busy. I teach. I read students' manuscripts. I'm a mentor for SCBWI. I don't like a passing minute with nothing to do, let's put it that way.

RS: You mentioned Virginia — while preparing for this interview, I remembered a Talks with Roger interview I'd done a few years ago with Naomi Shihab Nye about The Turtle of Oman. We were talking about it being this quiet, slow-burn book, and I asked her, "How does Virginia feel about this?" She said, "Well, Virginia did make me put people into the book," because in the original manuscript it was just a couple of houses. When I think of publishing today, so much of it is very high-concept. Authors can give you the plots of their stories in this one, exciting, action-packed little statement. I can't do that with You Go First — which is not a criticism!

EEK: No, I totally understand. The phrase "quiet book" — if you were to ask people to define it, it would probably differ from person to person. I like the word "subtle" more than "quiet." It's something that Greenwillow does really well, especially with middle grade — stories about the subtleties of life and how small events can change our lives in a big way, even if we don't notice it at the time.

RS: There's a very practical tone in your books. There's no moaning about things, which seems to work well with the slow burn that I'm talking about. The language is always very crisp and is always moving forward.

EEK: Thank you.

RS: I think of that scene where Charlotte is in the library and she overhears the friends of her friend talking about her. Oh my God, it's devastating, and it has its effect because readers don't see you working up to it.

EEK: Yes, in contemporary realistic fiction the foreshadowing is much more subtle, because you're not foreshadowing a big battle scene or something like that. It's foreshadowing small actions that characters might take — because that's how life is. My novels always start with a character first. I tell my students that, as writers, it's our job to embody, not to report. What does it feel like to hear your friends making fun of you in front of other friends? I always try to actually put my feet in the character's shoes.

RS: When you say you start with the characters, does that mean you knew Ben and Charlotte's relationship to each other?

EEK: I did not. The very early concept of the book began with Ben, and it grew out from there. I knew I wanted to write something that taps into the idea that you never struggle alone. And secondly, I think young people, and even adults for that matter, have this idea that if we were somewhere else or if we did XYZ, our lives would be so much better. I wanted to show that no matter where you are — whether you live just outside a big city like Charlotte or in a small town like Ben — we're all connected and sharing similar troubles, those kinds of universal experiences.

I knew I wanted to put the characters geographically far apart but then connect them, and I knew that I wanted to show their lives in parallel, how similar things are happening to both of them at the same time. My intention was for the reader to see that happening, but neither of the characters would know, because obviously they're not privy to all the same information. My hope is that readers will see, okay, these are two kids who are different from each other and different from their peers, living in different parts of the country, experiencing the same things — and maybe I'm experiencing those things too. There are other people who feel like I do. That's my intention with pretty much all of my books, actually.

RS: You seem very comfortable — in a way that not all writers are — with incorporating into your stories contemporary technology that people use to connect with each other.

EEK: I do use my own experiences to inform what I'm writing, but I have to remind myself that when I was my characters' age it was the eighties, and it was a different time! The context has changed. Also, some writers have a fear of dating their work if they include too much technology, but if you don't include it, you're also dating your work, so there's a fine line there.

RS: Meg Medina said that in Merci Suárez Changes Gears she used something like Snapchat, but she called it something else so that she didn't have to be bound by readers' expectations of a particular device or technology.

RS: Meg Medina said that in Merci Suárez Changes Gears she used something like Snapchat, but she called it something else so that she didn't have to be bound by readers' expectations of a particular device or technology.EEK: One thing I think is effective is when an author might say, "I looked at his profile," without saying "Facebook profile" or anything specific, so whatever the reader infers is fine. But I also think about those books with dated information that doesn't take away from the novel, like Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret. The goal is always to tell an honest story, and the reality today is that kids have phones and apps and all this other stuff, so you have to think about how to incorporate that. It's tricky.

RS: Some books will transcend their time. Most don't, if we're being blunt, but some will. I'm not sure that the technology is the sticking point either way.

EEK: Agreed.

RS: What was your own childhood reading like in the eighties?

EEK: Not surprisingly, a lot of Judy Blume. I think I read all of her middle-grade books. I read a lot of Sweet Valley High, and I wrote a lot of Sweet Valley High knockoffs.

RS: Were you a Jessica or an Elizabeth?

EEK: I was definitely an Elizabeth.

RS: Why did I even have to ask?

EEK: I've always been a very avid reader, from a very young age. I also like scary stories. Back in the eighties, that category of middle grade was not as wide as it is now. Like a lot of people, I jumped straight from reading Judy Blume to Stephen King. I have to tell you, I also liked V. C. Andrews.

RS: You're exactly the age, then, of when I first became a librarian. The girls in the public library I was working at were all crazy about Flowers in the Attic. That was the big forbidden book.

EEK: Yes, it was. I read all the books that she wrote before she died. Once I found out a ghostwriter was writing the rest of the books, I quit reading them. I thought, well, they're not hers.

RS: I hear E. L. Konigsburg in your writing. With her and with you, there's this assumption that kids are smart. Which is more rare than you might think in books. If there are smart kids in a book, some authors feel compelled to explain why they're smart. But you don't explain it — you seem to accept your characters for who they are.

EEK: Thank you for saying that. If my characters change throughout the book, it's not that they've lost weight or made the cheerleading squad or kicked the winning goal. It's about interiority. They change the way they feel about themselves — that's what is important to me. It's aggravating when adults condescend to kids, and I feel like we do that a lot even if we don't realize it. Adults think of kids as these empty vessels who need to be filled up with all of our knowledge, when they're complex, three-dimensional human beings. Their logic and behavior don't always make sense to adults, but that's because we're adults. They have their own opinions, feelings, thoughts, and emotions. You have to talk to them and respect their viewpoints. Too often adults think that kids must respect us, but then we forget that we should also respect them. It goes both ways.

RS: And I think it's more than respect, too, because it's respect born from understanding. It's the understanding, as you said, of that young person as their own person. You start there. You don't start with whatever it is you want to put into that child.

EEK: We think of kids as having a lot of growing up to do. So do we all, is what I say. Kids are evolving, but just because we're adults doesn't mean we're finished.

RS: I hope not. That's why I'll never get a tattoo. Because sometimes when you look at things that you thought were really wonderful even just five years ago, you think, oh my God, how could I ever have been into Sex and the City?

EEK: That's absolutely true. We're forever evolving. The thing with young people (and one of the many reasons I love writing for them) is they're in this terrible limbo where adults are telling them to be themselves, and then when they try to be themselves, their peers judge them.

RS: And the adults judge them, too.

EEK: Yes, and then the kids are like, okay, well, I guess I need to conform so I'll be accepted. But they're still miserable, because they're not being true to who they are. They want people to notice them, but at the same time they don't want people to notice them. It's this world of contradictions. We ask a lot from young people in that age group, and to top it all off we're often patronizing to them: "Everything will work out if you just be yourself. Why do you need those shoes? It's not a fashion show at school." It takes a lot of moxie to be able to rise above all that and just be who they are.

RS: What was your spot in the school constellation? Were you a popular kid, a loner?

EEK: I was not a popular kid. I was fairly quiet. I was a bookworm. I was trying to figure out how to be pretty, how to be popular, and I could never quite figure it out, because at the end of the day, I was trying to do things that were not true to my personality. For example, I tried out for the cheerleading squad. I was horrible; didn't make it. Tried to change my hairstyle; looked horrible. That's the kind of kid I was. I didn't think I was enough, so I was always trying to be better. That's where a lot of my books come from. I want young people, even if it's just for the duration of reading one book (hopefully mine, but anybody's!), to know that all they have to be is the best version of themselves. They don't have to be the prettiest, most handsome, most athletic, most popular — just the best version of whoever they are. It took me a long time and a lot of pain to try to figure out the hierarchy and put myself in there somehow. But it doesn't work that way.

RS: Do you think that's why you're writing for children?

EEK: Yes. I remember what it was like to be alone at lunch. I was always the kid who only had one or two best friends, not a huge entourage, so if my friend didn't have the same lunch period as me, I was on my own. I remember what it felt like to walk around and pretend like you knew where you were going, like Ben does, or to be like Charlotte and find a place where you feel emotionally safe. I know what it feels like to have something that you care about, that gives you joy, like Charlotte has her rock collection, and Ben has Harry Potter and Minecraft. I had books. Writing them and reading them.

RS: And still do.

EEK: And still do, absolutely.

More on Erin Entrada Kelly from The Horn Book

- 2018 Newbery Medal Acceptance by Erin Entrada Kelly

- Hello, Erin Entrada Kelly: Profile of the 2018 Newbery Medal winner

- Review of Hello, Universe

- Review of You Go First

Sponsored by![]()

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!