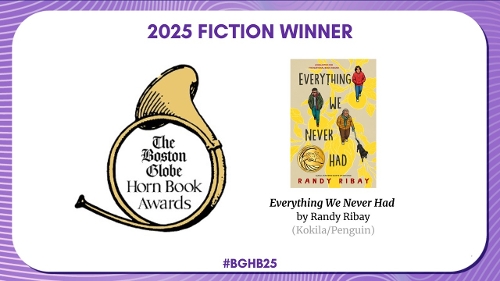

Everything We Never Had: Randy Ribay's 2025 BGHB Fiction Award Speech

One of the most frequent questions I get as an author is how I find the idea for each book. I usually have an origin story ready to go. It’s eloquent, linear, concise, and often…oversimplified. After all, how can we pinpoint the germination of an idea that’s been watered by so many drops of rain?

One of the most frequent questions I get as an author is how I find the idea for each book. I usually have an origin story ready to go. It’s eloquent, linear, concise, and often…oversimplified. After all, how can we pinpoint the germination of an idea that’s been watered by so many drops of rain?

|

| Photo: Susannah Richards. |

The story I tell about Everything We Never Had begins with the birth of my son five years ago. Like all new parents, I wondered, How do I do this? More specifically, How do I become a good father? To answer this, I had to — as my brilliant editor Namrata Tripathi often prompts me to do — find the questions behind the question. What did I appreciate about my relationship with my own father and want to pass on? What did I want to do differently? What did I still need to heal from? This led me to wonder: how would my father — and his father — answer those questions? I eventually arrived at the idea of exploring father-and-son relationships across several generations of a Filipino American family through a novel in which you see the characters as teenagers in their own timelines and as fathers or grandfathers in the other intertwining timelines.

While all of this is true, it’s incomplete. Many other things were going on in the world and in my life around that time, which likely influenced the formation of the novel’s idea. The start of the pandemic. A series of anti-Asian hate crimes. The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. Wildfires that turned our Bay Area skies orange. Also, I was still teaching high school English. I was serving as a judge for the National Book Awards. I was watching Gilmore Girls as I fed our newborn in the middle of the night.

As any good educator knows, one of the most difficult things to do well is to simplify a complex idea. I believe the fiction writer’s task is the same — and not only when we’re sharing the inspiration for our stories. Within a few hundred pages, we attempt to render lives. For those of us who write for children, we’re depicting young people as they figure out the world and themselves.

I approach this by excavating the layers of my characters’ contexts. Their back-story — home situation, family dynamics, significant events in their past, etc. — but also what we might call their understory or overstory: the interwoven factors that impact them directly and indirectly, visibly and invisibly. Gender, race, socioeconomic class, sexuality, disability, language, geography, religion, nationality, history, and so on.

As someone who never read a book with a protagonist who shared my ethnicity until college, it’s an honor for me to be able to do this with Filipino American characters. It’s thanks to the collective work of so many that I’m able to, and that students growing up in the United States today get to read about more than straight white kids in boarding schools. While there’s nothing wrong with telling those stories, their overrepresentation — and the simultaneous underrepresentation of so many other stories — harms everyone, as Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop explained powerfully when she introduced the concept of books as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors.

[Read Horn Book reviews of the 2025 BGHB Fiction winners.]

At the same time, writer Elaine Castillo warns us against overemphasizing the practice of reading stories about marginalized communities as primarily exercises in empathy. In doing so, she says that “we largely end up going to writers of color to learn the specific — and go to white writers to feel the universal.” To Castillo’s point, I’m happy if you read my book and learn more specifics about Filipino American history and culture, but my primary goal isn’t to teach you facts. I’m not an anthropologist or a historian. I’m a fiction writer. I’m trying to render complex lives on the page, and doing so effectively demands examining the ways in which my characters’ specific personal, political, and historical circumstances intersect and interact.

To that end, I hope readers don’t overlook the universality of Everything We Never Had. It’s about Filipino Americans as much as it’s about Americans and America. About the way in which this country exploits and ravages other lands, entices the people of those lands to immigrate with promises of high-paying work, and then treats them as nothing more than disposable labor. About how freedom is humankind’s natural state, and people will inevitably assert their full humanity by fighting for fair wages and safe working conditions as they try to make a new home for themselves. About how the formal and informal machinations of Empire will try to shut this down and shut the door by criminalizing and demonizing, threatening, fostering internal divisions, rewriting history, manufacturing crises. It’s happened repeatedly throughout this country’s history. It’s happening now through book bans and immigration bans; the suppression of academic freedom, dissent, and protest; assaults on birthright citizenship; and the deployment of ICE to detain, disappear, and deport.

Everything We Never Had is also a story about how real people — often young men of color — are caught within this brutal trap. About how amidst this, they are still coming of age, still trying to figure out who they are and how they fit into the world. About how they may survive — but not always whole, creating wounds that bleed into subsequent generations.

We see this painful truth in one of the final scenes between Chris Maghabol and his father, Emil, in which Emil gives up trying to repair his relationship with Chris. Yet as Emil exits, Chris’s son, Enzo, enters the scene, and we see how this is not the end of the Maghabol boys’ story. We see that healing is possible if we — individually and collectively — resist imitating the system’s oppressive attitudes, which poison our personal relationships and our souls as much as they poison our society. We see how instead of measuring success by our ability to increase profit, we must measure it by our ability to expand our love.

From the January/February 2026 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. For more on the 2025 Boston Globe–Horn Book Awards, click on the tag BGHB25. Read more from The Horn Book by and about Randy Ribay.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!