Field Notes: Teaching Flying Lessons & Other Stories

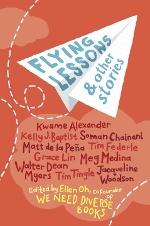

In a foreword to the paperback edition of the groundbreaking anthology Flying Lessons & Other Stories — edited by Ellen Oh, first published in 2017 in partnership with We Need Diverse Books, and dedicated to the late Walter Dean Myers — Christopher Myers writes, “Imagine…this book you are holding, Flying Lessons, as series of homes, of stories, a neighborhood of story-houses, and you are invited into them all. Please make yourself comfortable. Each story, each kind of storytelling, is different, but you are welcome in all of them.”

In a foreword to the paperback edition of the groundbreaking anthology Flying Lessons & Other Stories — edited by Ellen Oh, first published in 2017 in partnership with We Need Diverse Books, and dedicated to the late Walter Dean Myers — Christopher Myers writes, “Imagine…this book you are holding, Flying Lessons, as series of homes, of stories, a neighborhood of story-houses, and you are invited into them all. Please make yourself comfortable. Each story, each kind of storytelling, is different, but you are welcome in all of them.” The welcoming spirit of Flying Lessons makes it an ideal vehicle for classroom writing prompts that encourage students to imagine their way into stories.

In a foreword to the paperback edition of the groundbreaking anthology Flying Lessons & Other Stories — edited by Ellen Oh, first published in 2017 in partnership with We Need Diverse Books, and dedicated to the late Walter Dean Myers — Christopher Myers writes, “Imagine…this book you are holding, Flying Lessons, as series of homes, of stories, a neighborhood of story-houses, and you are invited into them all. Please make yourself comfortable. Each story, each kind of storytelling, is different, but you are welcome in all of them.” The welcoming spirit of Flying Lessons makes it an ideal vehicle for classroom writing prompts that encourage students to imagine their way into stories.

Oh’s volume presents ten tales from a diverse range of authors, stories of young protagonists finding their way on the basketball court, on a pirate ship, on a beach in Spain, in an ordinary school hallway. Mr. Howe is the ninth-grade English teacher in the collection’s lead story, “How to Transform an Everyday, Ordinary Hoop Court into a Place of Higher Learning and You at the Podium” by Matt de la Peña. On the first day of school, the narrator says, “After Mr. Howe goes around the room, having everyone introduce themselves, he’ll ask the class to pull out a sheet of paper. And he’ll give you the first of the seventeen thousand writing prompts he’ll assign over the course of the semester.”

Mr. Howe could be me: I can think of no better way to describe how I teach than to say that I teach with writing prompts — expository prompts to get students to think their way into ideas in the stories, open-ended prompts to encourage them to think for themselves, and creative writing prompts to spark imaginations. Like Mr. Howe’s class, my students write so much that they get comfortable with it and with critical thinking. Along the way, they develop a voice in their writing and pride in their improvements. They do most of the reading and writing in class so I can help as they write — answer questions, assist with grammar issues, and read one-on-one with students who need to get better at hearing how their sentences sound. Thus the classroom becomes a reading and writing community.

I know that many students simply read words and don’t consider essential ideas and themes unless a good teacher finds ways to engage them. Most teachers discuss stories, give quizzes (as do I sometimes), and then assign writing (if they do at all). But whole-class discussions don’t engage everyone; the few students who have put effort into their reading participate, and everyone else is quiet. Writing involves everyone; students quickly realize that they must read well so they can write well, and they quickly get better at reading, writing, thinking, and imagining.

Mr. Howe’s first assignment is for students to “describe one thing you did this summer. And one thing you learned.” As readers find out, the short story they’re reading is what the narrator wrote in response to Mr. Howe’s prompt. What the narrator did that summer was to try to prove that he was ready to compete against the best basketball players at the gym, namely the older Black men who, at first, call him “Mexico” and tell him to go back to the barrio. The best of the best was Dante, quiet but intimidating, a man of few words. Through his interactions with Dante, the narrator comes to understand that “when a man who stays mostly quiet offers advice, you take it.”

So I use an expository writing prompt that asks students to delve into Dante’s character and the value of the life lesson he teaches the narrator. I simply ask them to describe that life lesson; once they do, we discuss how the same lesson applies to the narrator’s father. I hope that, like the narrator, my students will use the process of writing to find new perspectives on their own experiences and preconceptions — that they will write to find out what they think.

* * *

Kwame Alexander’s contribution, “Seventy-Six Dollars and Forty-Nine Cents,” is a “story-in-verse,” in which narrator Monk’s English teacher assigns students to write a memoir. Because this entry is a series of poems, it is perfect to teach both memoir writing and poem writing. I use some of Alexander’s poem titles as inspiration for students’ writing assignments, usually reading aloud three or four examples and letting them choose which prompt connects. “My Name Is Monk” can inspire poems about where students’ names came from. “I Was the Kid” gets them writing about their childhoods. “Lisa Castillo” is a brief poem about a person in Monk’s life, so students can see how they might write memoir poems about people in their own lives — a friend, a parent, a relative — using the poem in the book as a model for how to select details and how to break lines. “So, Here’s When It Happened” is a poem about a particular moment, easy inspiration for writing narratives about memorable moments in students’ own lives.

Grace Lin’s story, “The Difficult Path,” set in Imperial China, begins with this attention-grabbing sentence: “When I was sold to the Li family, my mother let Mrs. Li take me only after she’d promised that I would be taught to read.” Narrator Lingsi tells of her childhood in the House of Li working as a servant, but also learning to read. The story becomes a testament to the transformative power of literacy when, later in the tale, as the household journeys to a temple near the sea, Lingsi is captured by pirates, and the beautiful and fierce pirate queen realizes that the girl knows how to read. “Teach me,” the pirate queen says, “and you can stay.” I ask students to write using this prompt: “Explain how, ironically, being captured by pirates makes Lingsi free.” Through writing, students take a closer look at the nature of Lingsi’s servitude and how her ability to read liberated her. (As Lingsi says at the end of the story, “For while the path before me might be difficult, it will be my own.”)

Jacqueline Woodson’s “Main Street” centers on the friendship between a white girl (the narrator) and a Black girl, Celeste, in a picturesque New Hampshire community where the red and gold autumn leaves “were the ONLY color in this town.” Both characters are dealing with loss (the narrator is grieving her mother’s death; Celeste is missing her father back home in New York City) and a sense of displacement (the narrator no longer feels she belongs in her hometown as her other friends abandon her; Celeste must cope with the microaggressions resulting from being the only Black kid in school). I put a guided reading/writing question on the board: “What does the narrator mean when she says, ‘New York is only four and a half hours away…But we both knew — the distance between New Hampshire and New York was forever away’?” Having the question in front of them before they begin reading, and knowing that they will need to address it in their writing, students can look for pertinent details and incidents as they go. Once they have completed the assignment, we share writings and discuss the story — and the discussions are always better because students have been given the chance to think things out ahead of time.

* * *

I love thinking up writing ideas, not to test students, but to actively involve them in their reading and to nudge them to read more deeply and write more thoughtfully. This may seem like too much writing, (maybe even to the point of ruining the reading experience!), but I have found that in my welcoming and safe classroom environment, students come to enjoy it — the opportunity to settle into a quiet time and let their minds do their thing. Kids like to be taken seriously, and they come to see how much I care about their reading and writing and thinking.

I’ve chosen just a few stories from Flying Lessons here to demonstrate my approach to reading and writing prompts, but all of the entries in the collection are rich and offer great opportunities for reading, writing, thinking, and imagining. All of the stories can lead students to other work by the contributors whose entries they especially liked, where they might see themselves reflected in the books they read. That is the spirit behind We Need Diverse Books. By choosing good, diverse literature and taking students seriously as readers and writers, I have tried to pass on my enthusiasm for reading and writing, turning my classroom into a community of learners, residents of that neighborhood of “story-houses” that Christopher Myers describes.

Ellen Oh on Flying Lessons & Other Stories

From the March/April 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!