Field Notes: Teaching News Literacy

During the 2020–21 pandemic school year, I was one of two fully remote fourth-grade teachers in my school. We each taught the required disciplines: English language arts, math, social studies, and science. Given the reduced allotment for time on camera with students, the flexibility of focusing on additional topics was almost impossible. Yet, while I was virtually teaching a life sciences unit, a “teachable moment” on news literacy came up.

During the 2020–21 pandemic school year, I was one of two fully remote fourth-grade teachers in my school. We each taught the required disciplines: English language arts, math, social studies, and science. Given the reduced allotment for time on camera with students, the flexibility of focusing on additional topics was almost impossible. Yet, while I was virtually teaching a life sciences unit, a “teachable moment” on news literacy came up.

We had been reading from our (outdated) science textbook about how crabs on Christmas Island scuttle across roads and yards to get to the ocean to mate and lay eggs. The skill being taught was supposed to be to compare and contrast, a requirement in fiction and nonfiction texts — a lesson that all literacy educators are familiar with and have tools in their toolboxes to address. My students were intrigued by a sidebar that said the crabs have a plant-based diet, eating such items as leaves, fruits, and flowers. One of the kids — an experienced social media user — then said something wild: crabs eat their babies.

They all perked up. What?! No way! Suddenly it seemed everyone was interested in the lesson. I hadn’t planned on teaching news literacy skills, but it became clear that we needed to take that detour. It was almost time for a break, so I asked my students to see if they could figure out what was true during our time off camera. What do red crabs eat?

When we reconvened, we started a list of what we’d found. The first few students said it was true: red crabs do eat their babies. But others found resources saying that wasn’t the case. One especially thoughtful student found a video with over 600,000 views (and counting!) that seemed to corroborate the notion that crabs eat their babies. During the break, however, I also had done some online sleuthing and found a reputable site with a fact-check disputing the exact video my student had shared. Like so much misinformation, there was some truth to the video, but it was highly misleading.

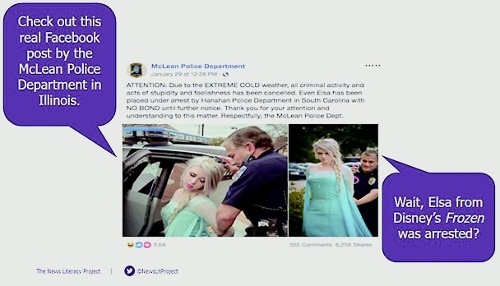

Rather than teach another lesson on comparing and contrasting, I engaged my students in a discussion about sourcing and how to know what to trust. We focused on reputable news organizations and how to spot signs of bias. We engaged in “lateral reading” : a method of going to other sites to learn about those sources that we weren’t sure about. And, for the following class, which coincided with the start of National News Literacy Week, my students worked through the News Literacy Project’s critical observation challenge. The topic: was Elsa from Frozen really arrested?

"Was Elsa really arrested?" Image courtesy of the News Literacy Project.

In this activity, I showed my students an actual social media post by a police department in Illinois about the “arrest” of Elsa. My students looked closely at the image and heatedly debated whether the evidence supported the claim. They evaluated the authenticity of the post, considered its primary purpose, and discussed how humor can lead to confusion.

We capped off this mini-unit by holding a Q&A with an editor of an online newspaper for kids about how news is made. The editor explained how reporters interview sources to get quotes for stories, how an idea gets fleshed out with additional research, and how those entities combine in the final story. My students were so engaged in learning about how to know what to believe that I wish I could have taught a whole unit on news literacy, but I had to stay on pace and adhere to the ELA curriculum. Still, I integrated news literacy when I could.

In today’s classroom practices on literature and nonfiction, news literacy is a must. Though the skill is not explicitly required in all narrative and informational reading curricula, students must be able to navigate online to meet the requirements of such curricula. It’s not only about research — it’s also about the background knowledge students bring to their understanding of texts and the world in general. Misinformation about a crab eating her babies might not be catastrophic, but what happens when our students mistake important information regarding their health or major world events? We would be best served to integrate news literacy knowledge, skills, and dispositions into our work at every grade level and across subject areas.

After that pandemic teaching year, I left the classroom to work full-time at the News Literacy Project (NLP). This nonpartisan education nonprofit is dedicated to equipping individuals with the tools to determine the credibility of news and other information, and to draw on the standards of fact-based journalism to know what to trust, share, and act on. The organization was founded in 2008 by Alan C. Miller, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who believes that individuals who learn to think like journalists will more effectively discern fact from fiction. We are building a movement to create better informed, more engaged, and more empowered individuals — and ultimately a stronger democracy. The Library of Congress recently awarded NLP the 2023 David M. Rubenstein Prize, which recognizes nonprofits for exemplary, innovative, sustainable, and replicable strategies to promote literacy and reading.

We work toward this mission through numerous free programs and offerings both for the general public and for educators. For educators, we developed the Framework for Teaching News Literacy, which provides support for integrating news literacy into existing curricula or as standalone units. We also have a working document of grade-band expectations for news literacy for districts interested in scaffolding its development from Pre-K through 12+. Checkology, NLP’s e-learning platform, is led by subject-matter experts, with lessons focused on such topics as “What Is News?” “InfoZones,” “Misinformation,” and “Practicing Quality Journalism.” Real-world examples and formative assessments allow students to stay engaged by getting an inside look at how journalism should work.

A ninth-grade journalism class using Checkology. Photo by Elyse Frelinger for the News Literacy Project.

Were I to go back in time and be asked to teach news literacy to my fourth graders, I would make sure to organize my lessons around essential questions from the framework such as: “How can we know what to believe?” and “What makes a piece of information credible?” I’d be sure to develop the competencies of distinguishing news from other types of information; understanding why professional standards are necessary to produce quality journalism and being able to apply understanding of those standards to discern credible information for themselves; demonstrating increased critical habits of mind to verify information and detect misinformation; and understanding why seeking and sharing credible information is a civic responsibility for supporting and maintaining a democracy.

I’m happy to report that my former district stopped using that (outdated) science textbook after students returned to in-person learning. Though I don’t know to what extent news literacy is taught there now, I know students will need the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to fulfill higher-level expectations in all of their classes. For this reason, I advocate for regular, cross-curricular integration. That way, whether they encounter an attention-grabbing crab in science class or a frustrating search during a research project, students will have a trove of tools to help them navigate this complex information landscape.

From the November/December 2023 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!