Gary Schmidt Talks with Roger

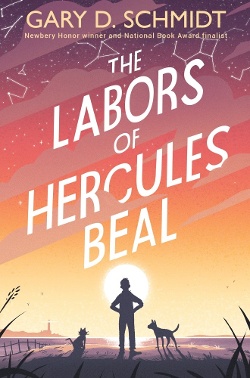

With The Labors of Hercules Beal, Gary Schmidt brings back an old character, Danny Hupfer (first seen as a youth in The Wednesday Wars) to teach a few things to new character Hercules Beal, who lives on the far end of Cape Cod with his older brother, Achilles, after the death of their parents. Just twenty-six days after his retirement from college teaching, I talked to Gary about the labors of both Hercules and himself.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

HarperCollins Children's Books

With The Labors of Hercules Beal, Gary Schmidt brings back an old character, Danny Hupfer (first seen as a youth in The Wednesday Wars) to teach a few things to new character Hercules Beal, who lives on the far end of Cape Cod with his older brother, Achilles, after the death of their parents. Just twenty-six days after his retirement from college teaching, I talked to Gary about the labors of both Hercules and himself.

With The Labors of Hercules Beal, Gary Schmidt brings back an old character, Danny Hupfer (first seen as a youth in The Wednesday Wars) to teach a few things to new character Hercules Beal, who lives on the far end of Cape Cod with his older brother, Achilles, after the death of their parents. Just twenty-six days after his retirement from college teaching, I talked to Gary about the labors of both Hercules and himself.

Roger Sutton: Are you enjoying retirement? Everyone asks me that, so I’m asking you.

Photo by Mayma Anderson

Gary D. Schmidt: I just started, really. I’ve only been retired for twenty-six days. It was the right time. Small, private liberal arts colleges are really struggling with resources and with the kind of teaching I want to do, and I’m tired of fighting those fights. If I’m going to be a full-time writer...I’m sixty-six —

RS: Me too. So will we be seeing your writing career going into greater gear?

GDS: I hope I can do some more. I’m not coming home and grading fifteen papers, leaving me with half an hour to write. That’s how I’ve been working more or less, in the cracks. I’m hoping I can write a little bit more slowly, a little bit more leisurely, without the “Okay, I can write one page right now” mentality.

RS: Do you have to make yourself write, or is it easy to keep yourself writing?

GDS: I don’t have to make myself sit down. I sometimes wake up in the middle of the night, and that can be the next two hours. I don’t know if it’s easy to make it good, but sitting down is the first stage of it, so that’s okay.

RS: All right, I need to know. Is this [holds up a copy of d’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths] part of your childhood?

GDS: Oh my gosh, absolutely. Plus the Norse myths one. There was a day — it wasn’t all that long ago — when I decided I really needed to get a good copy, and I found an old, signed copy of the Norse one. It’s just wicked cool. How many people could say that, right? That book has been so inspirational for so many people.

RS: I ask because we have Hercules in your book, but also I’ve noticed a trend among these interviews I’ve been doing for years now: when people mention the childhood book that inspired them the most, this tends to be the one. Men and women, realists and fantasy writers. Why?

GDS: I loved it, and I loved Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. When I was in sixth grade, we visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City on a class trip. I saw the Edith Hamilton book and purchased it. My friends looked at me like, Really? That stupid paperback? With no pictures? But I still have it. You’re right, though, the d’Aulaires’ was a big inspiration. Those pictures are amazing. Now there’s Rick Riordan, who’s got the corner on mythology. I wonder how many kids are still looking at that book.

RS: Betsy Hearne used to complain to me that her incoming undergraduates didn’t know squat about classical mythology anymore.

GDS: I don’t remember studying it in school. I do remember loving those two books. I never owned the d’Aulaires ones as a kiddo. You know how when you’re a kid you have favorite books in the library, and you know exactly where they are? I lived in a little town named Hicksville on Long Island, and I would look at the d’Aulaires’ books, probably well beyond the recommended ages. It was the illustrations that really moved me.

RS: What has been your sense of young people coming to college with knowledge of mythology? Do they know it?

GDS: I think they do. One of the most popular courses at my college was classical mythology. My temptation is to say it’s because it was easier than an English literature class, but that might not be fair. I think it’s just that kids still remember these stories and love them. During my first year teaching at Calvin, I listened in on a children’s literature course, and it was, oddly enough, on mythology in children’s books. The professor said she was walking home once and a fourth grader leaped out from a hedge, held his arm out, and said, “I’m Perseus. This is Medusa. You are turned to stone.” She said at that moment it didn’t matter if it was the third century BCE or twenty-first-century Grand Rapids, Michigan, the story was just as good.

RS: Why did you decide to name your hero Hercules? What came first, the boy or the name?

GDS: The boy. I knew he was going to be a beat-up kid. I knew that there was going to be loss and some loneliness. When I was a kid, my grandmother lived on Cape Cod. I absolutely loved it. We would drive all the way out to Provincetown; the town just below Provincetown is Truro. There’s a dune there, as in the book, and when you get to the top, you can see Cape Cod Bay on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other. I thought that was incredible. There’s a great line in Thoreau’s Cape Cod where he talks about how a man can stand on Cape Cod and put all America behind him. It’s literally true. You can put all America behind you, which these days is maybe a good thing to do now and again. It sounds like strength — I can put all America behind me — but it also sounds awfully lonely. That was the inspiration, in some ways, for that character and his loneliness, because he’s lost his parents. There’s some interesting irony in giving him a name that’s so incredibly strong. When my second son was in fifth grade, he was the smallest kid by far in his grade, which isn’t horrible, but he was also smaller than any kid in fourth grade. That was hard for him. That situation gave me a sense of those opening pages, when Hercules hasn’t started any kind of growth spurt yet. It seemed like a good way to begin, where he doesn’t have a lot going for him. How do we watch him as he comes to a new place over the course of the next school year? He doesn’t even get to go back to the school he was at. He doesn’t get to go to school with his close friends. None of that is there, so he’s isolated.

GDS: The boy. I knew he was going to be a beat-up kid. I knew that there was going to be loss and some loneliness. When I was a kid, my grandmother lived on Cape Cod. I absolutely loved it. We would drive all the way out to Provincetown; the town just below Provincetown is Truro. There’s a dune there, as in the book, and when you get to the top, you can see Cape Cod Bay on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other. I thought that was incredible. There’s a great line in Thoreau’s Cape Cod where he talks about how a man can stand on Cape Cod and put all America behind him. It’s literally true. You can put all America behind you, which these days is maybe a good thing to do now and again. It sounds like strength — I can put all America behind me — but it also sounds awfully lonely. That was the inspiration, in some ways, for that character and his loneliness, because he’s lost his parents. There’s some interesting irony in giving him a name that’s so incredibly strong. When my second son was in fifth grade, he was the smallest kid by far in his grade, which isn’t horrible, but he was also smaller than any kid in fourth grade. That was hard for him. That situation gave me a sense of those opening pages, when Hercules hasn’t started any kind of growth spurt yet. It seemed like a good way to begin, where he doesn’t have a lot going for him. How do we watch him as he comes to a new place over the course of the next school year? He doesn’t even get to go back to the school he was at. He doesn’t get to go to school with his close friends. None of that is there, so he’s isolated.

RS: Is that how your novels tend to work themselves out? It sounds like you had a core idea about one boy and his loneliness, and then as you tell the story, his life starts to branch and flower. Is that how you tend to write as well?

GDS: Yeah. I don’t have it all planned out, but I have a sense that he’s going to grow and by the end he’s not going to be in the same place. But I don’t know how that’s going to happen. I have to see what influences him, what things he comes up against, to see how he’s going to respond. In this book, I had the structure of all these labors. In Okay for Now, I had the Audubon birds. And in The Wednesday Wars, I had Shakespeare’s plays. The mythical Hercules does lose his family. That inspires his labors, to get past that grief. But here, with each labor, I have to figure out how my Hercules is going to reenact it in the modern world and what that is going to give him, how that labor is going to get him to a different place.

RS: I would imagine a danger in such a structure is, one, having to contort your character’s story to get all the labors in, and two, stopping it from becoming repetitive. “Here comes another one.”

GDS: That’s an especially big problem with Hercules, because a lot of the labors are about finding and killing some animal and then schlepping it back to the king. That was one of the most difficult parts of the novel, to take these stories about dead animals and work them out differently each time. And I wanted to make sure that each task shows a little bit of growth, even if it is similar in terms of the kind of thing classical Hercules had to do. So my Hercules dealing with the cat, for example, is not all that different from him handling the coyotes, but I wanted them to feel very different. He keeps the cat, ugly as it is. But he sends the coyotes to the Humane Society up in Maine, where they’re going to be happy beyond belief. In the first situation he kind of falls into it, but in the second, he’s going to act to bring real happiness to someone else. You can’t believe how many sheets of paper I had all over the place: “Don’t do this; you did this already; oh no, don’t do that.”

RS: Did you feel like you were kind of grading yourself in Lt. Col. Hupfer’s responses to each of Hercules’s assignments?

GDS: I remember writing pieces where you had to have a certain number of words. I resented that, so I did what Hercules does at first: I tried to make it exactly whatever the minimum was, e.g., 150 words. It helped me get through those assignments. With the Colonel’s responses, I wanted Hercules to feel that there was a kind of growing understanding, an affirmation that was going on. A lot of kids — all kids, maybe — when they get something back from a teacher, they want some sort of serious engagement. He desperately wants that partly because he’s lost his parents, but partly because we all want that affirmation. By the end, that becomes less important. Hercules doesn’t need it as much, though he still gets it.

RS: And it’s work. I felt the relationship between the boy and his teacher grow as time went on. Hercules stopped writing the absolute minimum and wrote what needed to be said. But you can also see the teacher starting to truly care for the boy, as much as he would never have admitted it.

GDS: That was fun to do, I have to say. I enjoyed that.

RS: Hupfer was a kid in The Wednesday Wars, right? You brought him back.

GDS: Danny Hupfer, right. In a later book, Holling, the protagonist of The Wednesday Wars, is killed in a car accident. I know, though in a sense it’s not important in this book, that Danny lost his best friend in eighth grade, and that’s something that stays with him. I also know—and this is just barely hinted at in the book because he’s not going to talk about it—that he also lost a platoon in Vietnam. He’s lost a bunch of guys. Those things weigh on him. He knows what grief is. He knows what loss is. And he recognizes it in this kid. When he gives this assignment, in a way he understands that this is exactly what the mythical Hercules did to get through things, and he hopes, deep down, that that is going to be true for this Hercules. But since the book is told from Hercules’s point of view, I can’t come out and say that in the book. It just has to be hinted at in very oblique ways.

RS: To paraphrase a question I asked Richard Peck maybe twenty years ago — “What is it about you and boys and old ladies?” — what is it about you and boys and teachers? Where does that come from?

GDS: Wait, you said that to Peck?

RS: He wrote a bunch of books with strong older ladies around to provide both humor and lessons.

GDS: Yeah. That’s really interesting. I don’t think I would have dared to ask him about that.

RS: We’re The Horn Book. We’re fearless.

GDS: I think it’s because I had some amazing teachers. I know everyone says that, but I had teachers who I feel like saved my life. Miss Kabaloff who took me out of the lowest level class in third or fourth grade and brought me into her class, which was the highest level. She taught me to read. Miss Kumpikas, who taught high school French, believed in us enough that she asked us to read Stendhal, Pascal, and Balzac. It was fantastic that she trusted us — that she thought we could do it. There are so many that I could name who were super important to me, and who did, in fact, affirm me and lead me in interesting ways. I was really hoping to go to Annapolis. If you had known me in middle school and high school that’s all we would’ve talked about — that someday I was going to go to Annapolis. I’ll be a second lieutenant, I’ll be career navy, I’ll tour the world. I’ll be on ships in the middle of the ocean. That’s all I talked about.

RS: There’s still time, Gary!

GDS: Well, as it turned out, you have to go see a congressman. And before I got into the congressman’s office, they asked me to go take an eye test. And they discovered what I think I had at least surmised, but my parents didn’t know: I’m as colorblind as a dog. I just don’t see colors. And suddenly that meant that it was all over. There’s no way you’re going to go to Annapolis or any of the academies if you can’t see colors. I was heartbroken. And my teachers were there when I needed them. Even in late high school, Mr. Halowich could say to me, “Okay, that’s one door closed, but what else is out there?” And I really needed that. So maybe these books are my big “thank you” to teachers. Since teachers are such easy targets in books, and right now, such easy targets for politicians, maybe I feel a need for that.

RS: I feel like, for a while, I was one of those kids, too. I had trouble with my peers. I just couldn’t make my thoughts gel with theirs too easily. But I would get a few teachers who seemed to understand my wavelength. And I really needed that relationship, to keep going.

GDS: I think our experiences were very similar.

RS: I’m also colorblind, so there’s that.

GDS: Are you really? Was that ever a problem for you in reviewing?

RS: Yes. And people joke I was on the Caldecott committee for The Invention of Hugo Cabret, which is in black and white. But yeah, I would always double check picture book reviews with Martha, Kitty, and Elissa and everybody because I really couldn’t be sure.

GDS: That would be me too.

RS: Since we’ve discussed your obsession with children and their teachers, I want to know what you learned as a teacher yourself. How did that affect your depiction of teachers in books, and what are you most going to miss about it?

GDS: This is the time to ask, because I’m suddenly feeling these pangs about it. I loved being in the classroom, I absolutely loved it. I didn’t like all the accoutrements around it, all the administrative claptrap. But I loved walking into the class, closing the door, and starting a class on, I don’t know, Beowulf. I think the thing I loved most about it was that I finally — it took a while — got good at giving people the space to explore, in discussion, ideas that were maybe only half-formed. But I could let my students be vulnerable enough to express them and, even as they were speaking, watch them come to some sort of solidity about those ideas. I love that moment when someone sees something for the first time. Or is able to articulate what she’s feeling or half-understands but now finds the words to make that clear and coherent. And then to walk out of the classroom and think, Something good happened.

I had a colleague who used to say, as I was walking into the classroom, “So, Gary, how are your students going to be different at the end of this class?” At first I thought, That’s a hard bar to reach every single time. But I would think about it every single time. How are they going to be different? What new understanding have they come to? What new insights as writers? Back to Beowulf: when Beowulf comes out from the mere holding Grendel’s head in the second part and says, “I tried to use Unferth’s sword, but I couldn’t bring it around to make it to kill Grendel’s Mother.” That’s a lie. The sword broke. He’s lying about it to protect Unferth, who had just attacked him in a previous section. At the end when we get to the line about how Beowulf was the most gentle, the most gracious of men it feels like a surprise, because he’s been killing things the whole poem. But then you remember what he did with Unferth. How do you put those things together? I love that stuff. I think — I hope, anyway — that might be something I grew into as I learned to teach better, to give students the space to be able to talk about ideas that may be only half-formed and to come out with a sense of competency. “I can do this.” But also a sense of “I can understand what this artist is doing.” I love that.

RS: Does that happen for you when you write? At the end of writing a book, do you feel like a different person?

GDS: Yeah, I would have never articulated it that way until you just said that. But I do think that is the case. I don’t necessarily believe in writing as therapy, though I understand how that can work. But it certainly is the case that writing the last two or three books have, for me, been dealing with my own loss. I lost Anne, my wife, to cancer. And I think writing about grief is a way of trying to understand how you recover from that. If it is recovery; maybe that’s not the right word. I do think in some ways those books have shown me steps to get past it. Though again, I don’t want to be exploitative. I don’t want to hand a reader something just because I want to not feel grief anymore.

RS: Right. “Help me work out my issues, dear reader.”

GDS: And we know books that do that, right? That’s not fair to the kid, to the reader. But with writing I’m trying to figure out certain things, and I do think in ways I have.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!