Welcome to the Horn Book's Family Reading blog, a place devoted to offering children's book recommendations and advice about the whats and whens and whos and hows of sharing books in the home. Find us on Twitter @HornBook and on Facebook at Facebook.com/TheHornBook

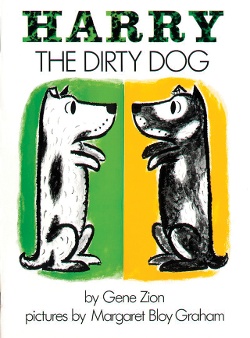

Margaret Bloy Graham's Harry the Dirty Dog: Still Spot On

This is the centennial year of illustrator Margaret Bloy Graham’s birth. Graham (1920–2015), who gave children lasting images of a good-natured dog “who liked everything, except…getting a bath,” is almost always associated with her then-husband, Gene Zion, author of Harry the Dirty Dog (1956) and three sequels...

This is the centennial year of illustrator Margaret Bloy Graham’s birth. Graham (1920–2015), who gave children lasting images of a good-natured dog “who liked everything, except…getting a bath,” is almost always associated with her then-husband, Gene Zion, author of Harry the Dirty Dog (1956) and three sequels. After the couple divorced, no one got custody of Harry and the series ended, although Graham went on to write and illustrate several other books.

This is the centennial year of illustrator Margaret Bloy Graham’s birth. Graham (1920–2015), who gave children lasting images of a good-natured dog “who liked everything, except…getting a bath,” is almost always associated with her then-husband, Gene Zion, author of Harry the Dirty Dog (1956) and three sequels. After the couple divorced, no one got custody of Harry and the series ended, although Graham went on to write and illustrate several other books.

The Harry books are classics that children still enjoy. Partly, it’s the stories’ simplicity: a dog wanders away and returns home, having learned that missing his family is worse than submitting to soap and a scrub brush. Being forced to wear a silly sweater because it is a gift from Grandma is humiliating, but re-gifting it to a bird is gratifying. The books are set in a distant era when trains spewed coal and mothers wore aprons, and when almost all the characters were white. (In the fourth book, 1965's Harry by the Sea, Graham included some people of color, reflecting a slow and belated acknowledgement of diversity in children’s books.) Even so, it’s the non-human characters whose dilemmas reflect children’s own; Harry helps readers negotiate the question of what makes us who we are.

The figure of Harry isn’t especially realistic. He has a boxy body, even a little out of proportion. His simple outlines, and the equally basic drawings of family members who all look alike, are punctuated with small details. There is the tiny car that the boy holds delicately by a string, and the carefully rendered bath toys and faucets on the old-fashioned tub. Somehow, Graham achieves a balance of generic and specific, as she propels Harry into motion. Digging a hole, socializing with other dogs in an improvised playground, leaning dangerously from a bridge to watch the trains going by--are all fun until they aren’t. Harry has fun transgressing rules, but in the end he wants to return to the security of home.

When I read the first book with my grandchildren, I remember the same feeling I had as a child, as Harry’s excitement turned to anxiety. The transitional picture is one where Harry walks glumly past a swanky restaurant. Through the window he watches well-dressed businessmen and families enjoying dinner; a waiter with his nose in the air looks exactly the type of person to enforce the “No Dogs” sign in the lower right corner. Harry’s attempt at independence has ended with an image of exclusion.

When Harry returns, his adventures have made him unrecognizable to his family--or so it seems. He is a black dog with white spots, rather than the reverse. When you read the book with children, this is a key moment to engage them by asking if the family truly thinks that Harry is a different dog entirely. The boy and girl are convinced that they have taken in a stray, as evidenced by their incredible excitement when the bath “worked like magic,” transforming the dog back into Harry. On the other hand, how could they have failed to identify their dog, even when he performs “all his old, clever tricks,” the ones which make him unmistakably himself? The mother and children look baffled as they watch Harry’s tricks, as if doubting their own perceptions. Maybe the parents are rewarding their kids with an unexpected opportunity to teach Harry a gentle lesson, or maybe everyone is participating in this harmless ruse, which ends with a serene Harry sleeping soundly on his familiar pillow. Readers may not be sure.

No Roses for Harry (1958) has a different plot but the same problem. When Grandma sends Harry a Christmas present of a handmade sweater with a pattern of beautiful roses, the dog feels humiliated by this Trojan horse of a gift and spends the rest of the book attempting to conveniently lose it. Nineteen-sixties expectations of gender are at work here; would Harry have been as resistant if the grandmother had sent him a sweater with some stereotypical male symbol, maybe footballs? In the end, it becomes clear that Harry just wants to be himself and is happy to receive a new sweater, white with black spots. It was the disguise not the flowers that made him uncomfortable. This story has a corollary, which sets it apart from the original Harry. When the offensive sweater finally unravels, a bird, perfectly happy with roses, weaves the wool into a home for her family. The lesson is that one creature’s embarrassing nuisance is another’s perfect gift, met with gratitude. One hundred years after Margaret Bloy Graham’s birth, that reassurance of difference, and comfort in being oneself, still matters.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Jonah Winter

This piece actually does address the gender stereotypes and lack of diversity -- I would hope that neither of these things nor the rooftop TV antenna were the ultimate takeaway from either this article or from these HARRY books, which clearly do have universal, lasting value, despite having been written in an earlier, less-evolved era. I'm happy to hear you read these aloud, but I think it's likely that children need far less "explanation" than one might think. When we impose our adult political concerns on children in this sort of context, we do them a disservice. Let them enjoy this classic dirty dog -- without turning the whole experience into a teachable moment about racism and sexism.Posted : Jul 31, 2020 02:30

Nan Stifel

I always need to explain the rooftop tv antenna when I read Harry aloud (along with period gender stereotypes and lack of diversity).Posted : Jul 30, 2020 07:26