Julie Hakim Azzam appreciates how Ekua Holmes's art in Hope Is an Arrow, a picture-book biography of Kahlil Gibran, brings history to life with bold colors and shapes. She also finds the book problematic in terms of cultural accuracy — and provides some historical perspective.

[Many Calling Caldecott posts this season will begin with the Horn Book Magazine review of the featured book, followed by the post's author's critique.]

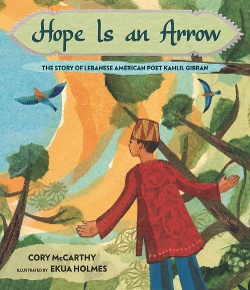

Hope Is an Arrow: The Story of Lebanese American Poet Kahlil Gibran

Hope Is an Arrow: The Story of Lebanese American Poet Kahlil Gibran

by Cory McCarthy; illus. by Ekua Holmes

Primary Candlewick 40 pp. g

6/22 978-1-5362-0032-4 $18.99

In this picture-book biography, readers are introduced to artist and poet Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931), whose work The Prophet is one of the most widely translated books of poetry ever published. McCarthy takes readers from Gibran’s childhood in politically fraught Lebanon; to his immigration to the U.S. and adolescence in Boston, where he missed his home (“Deep is your longing for the land of your memories”) and where his talent as an artist was first noticed; to his return to Lebanon to study, where he began his journey as a poet. Inserting lines and stanzas from The Prophet throughout, McCarthy highlights the moments and episodes of Gibran’s life that seem to have influenced his work. Holmes’s (Dream Street, rev. 9/21) collage and acrylic illustrations work well to highlight the contrasting settings of Lebanon and Boston of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries; her art is particularly stunning in the opening pages that depict Gibran’s childhood days. Extensive source notes do much of the work fleshing out this biography by providing additional information about Gibran’s life and work; also appended is a brief bibliography. ERIC CARPENTER

From the July/August 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The illustrations in Hope Is an Arrow: The Story of Lebanese American Poet Kahlil Gibran have artistry, depth, and texture. Holmes manages to blend simplicity with detail, texture, and dimensionality in a way that works really well for her subject matter. Her collages incorporate actual photographs of people from the historical period into paintings, alongside various bits of newspaper and fabric, all of which produce a vibrant effect in which history is brought to life with bold colors and shapes. She also incorporates metaphors such as birds, which soar in the sky, or cleverly transform from the flapping pages of a book, and other objects that are significant to Gibran (the bay laurel leaf on the book’s title page is inspired from a design Gibran made for his sister Mary).

In my reading as a person of Lebanese descent, though, I found that some of the illustrations lacked cultural accuracy. For example, the image on the cover shows the young Gibran standing in a forest looking up at the “great cedar trees [that] inspired him.” The point of view is from the ground looking up at the ancient, majestic cedar trees. The trees in the illustrations don’t look like cedar trees, though. These have long trunks with tufts of greenery at the top; cedar trees have a distinctive triangular shape and feathery needles on long-limbed branches. Other illustrations seemed to represent North African style of dress, complexion, and facial features rather than what you'd expect to find in Lebanon. (Growing up, I noticed that many Americans confused Libya [in North Africa] with Lebanon; perhaps it's because they were both Arabic-speaking countries starting with L, but in this case, it really does seem like Gibran's clothing is more Libyan than Lebanese.)

There is a history of controversy surrounding the ways in which Kahlil Gibran has been visually represented. The white photographer F. Holland Day, who was a supporter of Gibran in his early days in America, took many of the surviving photos we have of the young Gibran. Day’s images are problematic because they amplify Orientalist stereotypes about the East. In Kahlil Gibran: His Life and Work, Jean and Kahlil Gibran write that Day “posed [Gibran] in mysterious Arab burnooses, just as he dressed Armenians in turbans, blacks in Ethiopian regalia, Chinese with flutes, Japanese in kimonos…Through Day’s lens ghetto waifs became ‘Armenian Princes,’ ‘Ethiopian Chiefs,’ and ‘Young Sheiks.’”

Hope Is an Arrow references Day’s work, which may be where some of the images I found problematic had originated. For example, the cover image shows young Gibran wearing Northern African-style clothing: a mid-thigh tunic, flowing pants, and what appears to be a beaded tarboosh (fez-like hat). There is a distinctive style of traditional dress in Lebanon for this period, and this isn’t it.

Again, Holmes's illustrations here are artistically impressive. You can spend time marveling at the depth and detail in each of the illustrations of this book. They are visually stunning and complex; I just wish the book was more a culturally accurate representation.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!