Megan Dowd Lambert discusses Marla Frazee's illustrations for How Elegant the Elephant: Poems about Animals and Insects, written by Mary Ann Hoberman: "Frazee takes Hoberman’s varied, playful verses and expands upon them to create a fully realized world that invites imaginative escape for readers."

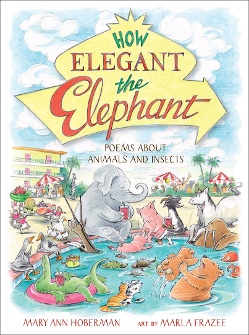

For years I’ve harbored a not-so-secret wish that Marla Frazee would illustrate a Mother Goose collection. With her Caldecott-worthy interpretation of Mary Ann Hoberman’s How Elegant the Elephant: Poems about Animals and Insects, she has delivered the next best thing. Through vivid visual characterization of a range of anthropomorphic creatures, ample humor across a multiday visually established plotline, and brilliant evocation of setting, Frazee takes Hoberman’s varied, playful verses and expands upon them to create a fully realized world that invites imaginative escape for readers.

For years I’ve harbored a not-so-secret wish that Marla Frazee would illustrate a Mother Goose collection. With her Caldecott-worthy interpretation of Mary Ann Hoberman’s How Elegant the Elephant: Poems about Animals and Insects, she has delivered the next best thing. Through vivid visual characterization of a range of anthropomorphic creatures, ample humor across a multiday visually established plotline, and brilliant evocation of setting, Frazee takes Hoberman’s varied, playful verses and expands upon them to create a fully realized world that invites imaginative escape for readers.

Perhaps the biggest stumbling block in this book’s consideration for the Caldecott will be debate over its eligibility as a picture book. At eighty pages, the collection is, well, elephantine compared to the length of a standard picture book, and its poetic text alone does not create an obvious “story-line, theme, or concept.” But longer books have won the medal (huge Hugo, for example), and a picture book is not reliant on text alone; at the form’s best, interdependent pictures and text combine to comprise an iconotext that holds meaning beyond the sum of its parts. Even wordless picture books have titles that prompt or guide readers’ engagement with illustrations — but that’s a topic for another time.

The topic at hand is how Frazee’s interpretation of Hoberman’s poems “essentially provides the child with a visual experience [...through] a collective unity of story-line, theme, or concept, developed through the series of pictures of which the book is comprised.”

In a word? She does so elegantly.

The first time I saw the jacket art and printed case underneath, I was intrigued by what seemed like a disconnect between the title and art. On the jacket, an elephant sits poolside, drinking a beverage through a straw, surrounded by other animals cavorting. A group of squirrels approaches with fruits held aloft to serve the animals, who seem to be guests at a hotel in the distance. The case cover shows, instead of single scene, smaller spot illustrations of animals engaged in various activities one might enjoy at a spa or while on vacation: a tiger gets a massage from a snake and moose toast marshmallows at a grill, for example. The picture of the elephant, however, is anything but elegant as it seems to be having a sneezing fit, dousing one of those fruit-bearing squirrel waiters from the dustjacket with what appears to be hot chocolate. Baffled, I opened the book to figure out how the title’s elegance might emerge. The answer: elegance emerges not in the elephant itself, but through the cohesion Frazee creates in her artistic creation of a peaceable kingdom/vacationland inspired by Hoberman’s words.

On the half-title page, squirrels appear again, though not clad in the smart red jackets and caps they sport in the book’s exterior design. Their nakedness would make them seem naturalistic, were it not for how they walk upright on their hind legs in a hurried line toward the page-turn to the title page. There, a zebra in a bowtie greets them as they enter a sleek hotel that would be right at home in the American Southwest, brightly colored, with mid-century modern lines, and cacti in the landscape.

The next spread in the front matter lists the book’s contents, sixty-eight poems with titles in approximate alphabetical order. Though some letters are skipped (G, K, N, Q, U, X), and some titles cheat a bit to fit into sequence (“It’s Fun to Be a Fire Dog,” counts as an F poem, “Each Time the Walrus” counts as a T), the presentation gives readers a structure to follow, and within that structure Frazee creates an orderly, exuberant animal kingdom on holiday.

The vacationers’ setting is inspired by a later-appearing poem, “Squirrel Hotel,” though other poems could have leant themselves to different locations — perhaps a house of worship evoked by “Praying Mantis,” an office building for “Monkey Business,” other work sites such as a firehouse or construction zone for “It’s Fun to Be a Fire Dog” and “Carpenter Ants,” respectively, or maybe most obviously a zoo for “Zoogeography.” Frazee’s choice of hotel demonstrates “excellence of pictorial interpretation of story” as it very naturally allows a range of animal staff and guests to interact in a setting more flexible than others might’ve been and more unexpected than a zoo.

In those interactions, Frazee uses her art to achieve vivid delineation of not just setting but characters and an episodic plot. A poem’s Brachiosaurus is depicted, not as a living, anachronistic visitor defying extinction, but as a large dinosaur-style play structure where birds and other small creatures frolic in a series of spreads to follow. After the moose toast marshmallows by a river, the fire dog (a Dalmatian, of course) shows up to put out a resulting grill fire. In a spread begging to be made into a poster, “So Many Kinds of Animals” take an outdoor yoga class, their bodies of “so many shapes and sizes” assuming the Crescent Moon Pose, and then the page turn shows a donkey burdened with a pile of colorful, rolled-up yoga mats before collapsing to rest on the facing page. Here, Frazee displays true illustrative genius, bringing the donkey’s episode to closure on a page with a poem that never mentions it, but is instead about a spider. As the donkey sleeps in a doorway to what seems to be a storage shed for yoga and fitness equipment, a spider drops down before its prone form on a “silken thread,” recalling Charlotte’s salutations to Wilbur from her web in the corner of the Zuckermans’ barn doorframe.

These examples of how Frazee connects one poem’s illustrated scene to later ones demonstrate her excellence in the illustration of the collection as a cohesive whole. The poems are not siloed into individual vignettes, a separate scene for every poem as though locked behind closed hotel-room doors. One poem or scene gives rise to another, all combining to depict a multiday stay at the hotel. Watch how Frazee depicts the day-to-day movement of time with subtle changes in color, shadow, and the sky, indicating movement from morning to nightfall, and morning again, until the final morning when a poem about the zebra offers a bookend to the one at the beginning, ruminating on “Zebra stripes / In white and black / From back to front / And front to back.”

In addition to my Mother Goose hopes, I have another not-so-secret wish for Frazee’s career: that the Caldecott Committee will finally give her a gold Medal to go with her trio of silver Honors. May it be so in 2026, to recognize how elegant the achievement she has made with this truly distinguished poetry book that functions like a picture book with its interdependent art and text.

[Read The Horn Book Magazine review of How Elegant the Elephant]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!