An Interview with Elizabeth Wein

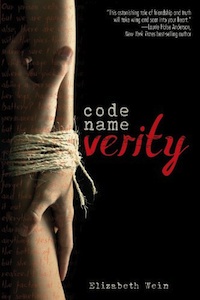

Author Elizabeth Wein is also a pilot, and her two most recent novels, Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire, feature young female pilots who ferry aircraft for Britain’s Air Transport Auxiliary during World War II.

Elizabeth Wein posing with a WWII-ear Lysander. Photo by Jonathan Habicht, courtesy of the Shuttleworth collection.

Elizabeth Wein posing with a WWII-ear Lysander. Photo by Jonathan Habicht, courtesy of the Shuttleworth collection.Author Elizabeth Wein is also a pilot, and her two most recent novels, Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire, feature young female pilots who ferry aircraft for Britain’s Air Transport Auxiliary during World War II. When Elizabeth was in Toronto recently for a book tour, she invited me to join her on a flight in a WWII plane — a Lysander, the same kind Maddie flies in Code Name Verity (Rose, in Rose Under Fire, flies mainly Tempests and Spitfires). Alas, the flight was cancelled. Instead, we had a conversation about Elizabeth’s work.

Deirdre F. Baker: You’ve made quite a chronological leap in the subject matter of your novels, roaming from The Winter Prince, inspired by medieval Welsh folklore and The Mabinogion; on to further Arthurian adventures set in sixth-century Ethiopia, or Aksum, in A Coalition of Lions, The Sunbird, and sequels; and now to books set during World War II. Can you talk a little about the connections between the stories?

Elizabeth Wein: People sometimes ask me, “Why do you write such different books? Why did you go from settings in sixth-century Britain and Ethiopia to Europe in World War II?” But they’re not so different, really. The Sunbird is a spy novel about a person who is captured, tortured, and enslaved, and he figures out what’s going on and brings down the regime. It’s essentially the same plot as Code Name Verity, with a heroic character — but set in a different time and place.

DFB: How do you see the protagonists and the nature of heroism developing in your stories?

EW: I think as readers we put ourselves in the protagonist’s place because we want to be like that person. That’s why sometimes we don’t like protagonists who aren’t all that nice; we want to relate to the protagonist. But with a heroic character like Telemakos in The Sunbird, I feel I want to be able to rise to the occasion; I want to be able to solve the mystery and endure the torture and not give any of my secrets away and maintain my identity throughout it all. I want to be like that. But I don’t know whether I’d be able to or not, and that’s something Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire explore. I’ve tried to look at different kinds of heroism in these books. My previous heroes are all pretty straightforward: they’re strong, heroic characters. So is Verity, but you don’t know that at first: you are presented with someone who has collapsed under pressure and appears to be a Nazi collaborator; you don’t really know what’s going on with her. Maddie’s is a different kind of bravery, and then Rose’s is another. There are many kinds. My favorite example is in Little House on the Prairie, when Ma is sitting in the rocking chair holding baby Carrie, and fireballs — ball lightning — come down the chimney and roll across the cabin, and one of them rolls under Ma’s skirts. “Mary couldn’t move, she was so scared. Laura was too scared to think.” So Laura runs and pulls the rocking chair away, but it’s not like she’s consciously being brave; it’s just that she has to do something. I think maybe what the difference is between my earlier books and the later ones is that I’ve started exploring the concept of bravery and the forms it can take.

EW: I think as readers we put ourselves in the protagonist’s place because we want to be like that person. That’s why sometimes we don’t like protagonists who aren’t all that nice; we want to relate to the protagonist. But with a heroic character like Telemakos in The Sunbird, I feel I want to be able to rise to the occasion; I want to be able to solve the mystery and endure the torture and not give any of my secrets away and maintain my identity throughout it all. I want to be like that. But I don’t know whether I’d be able to or not, and that’s something Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire explore. I’ve tried to look at different kinds of heroism in these books. My previous heroes are all pretty straightforward: they’re strong, heroic characters. So is Verity, but you don’t know that at first: you are presented with someone who has collapsed under pressure and appears to be a Nazi collaborator; you don’t really know what’s going on with her. Maddie’s is a different kind of bravery, and then Rose’s is another. There are many kinds. My favorite example is in Little House on the Prairie, when Ma is sitting in the rocking chair holding baby Carrie, and fireballs — ball lightning — come down the chimney and roll across the cabin, and one of them rolls under Ma’s skirts. “Mary couldn’t move, she was so scared. Laura was too scared to think.” So Laura runs and pulls the rocking chair away, but it’s not like she’s consciously being brave; it’s just that she has to do something. I think maybe what the difference is between my earlier books and the later ones is that I’ve started exploring the concept of bravery and the forms it can take.DFB: Rose Under Fire is set, partially, in the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp, where heinous medical experiments were performed on prisoners dubbed “Rabbits.” Can you tell me a little about doing the research for Rose Under Fire?

EW: I do my research the same way for every book I write. I start with books; I do the reading. One of the great things about doing research this way is all the bibliographies you find, which put you on to other stuff. What I started with for Rose Under Fire was a big stack of survivor autobiographies. I had a representative sample of several different nations. I had one German woman; a couple of French women; one was a Polish woman who hadn’t been one of the “Rabbits” and one was a Polish woman who had; one of them was a countess and an intellectual working for a Catholic university in Poland; one was a student; one was a Resistance worker; one was a Communist. And there was a Dutch woman as well. So there was a real mix there. At first I was very reluctant to read the survivor accounts. I didn’t know what I would find, and I was apprehensive about the magnitude of the horror I expected to encounter.

So I was very much surprised by the amount of hope that I found in their stories, how uplifting they were, and how personal; how individual the voices of these survivors were. One of my favorite accounts is by a French woman named Micheline Maurel, who includes a lot of her own poetry in her autobiography. She has such a wonderful sense of self-parody; she’s able to step outside and look at herself and be a little bit mocking. She was imprisoned in Neubrandenburg (which is one of Ravensbrück’s satellite camps and figures tangentially in Rose Under Fire). Maurel says it was worse than Ravensbrück: at Ravensbrück, the guards processed all the stuff they took from the arriving prisoners, so you had a chance to get hold of cigarettes and pencil stubs and bits and pieces of fabric. At Neubrandenburg you had nothing but your prison uniform and the bowl they issued you. It was a very hard life. Maurel worked in a factory making these little bits of springs and wire, and she didn’t really know what they were for, but everyone assumed that they were for weapons (just as in Rose Under Fire, Rose is assigned to a factory making electrical relays for bomb fuses). On her way out of the factory every day Maurel would reach into the bins where they had been putting all the parts that they had made that day, and she would grab handfuls of them and stuff them in her pockets. She would walk out and then she would scatter them in the woods on her walk back to camp — this was her one act of defiance.

Rose, when she first turns up at Ravensbrück, is more angry than scared. I got that also from Micheline Maurel: she said she used to sit working in the factory feeling rage. She’d been working for the Resistance; she’d been fighting against the enemy; and now she was doing this stupid, pointless factory work. Meanwhile, the war was going on without her. So the accounts gave me lots of different perspectives; it wasn’t all fear and terror and horror. There was a lot of other stuff going on. And of course there were friendships and companionships that people were forming that sustained them.

DFB: You bring the Girl Guides into your story. I was very interested to learn that there was a whole company of Girl Guides in Ravensbrück.

EW: That’s right. They were Polish Girl Guides who were involved in Resistance work. I knew that the local unit of Girl Guides within the camp helped to save some of the records at Ravensbrück from being destroyed, and I thought, That is really cool; I must bring that into the story. And of course making Rose a Girl Scout created a parallel between her existence in the U.S. as an ordinary American teen and the people she meets who have been involved in the war effort.

DFB: There’s a gulf between the naiveté and protectedness of the American Girl Scout Rose and the level of risk involved for the Polish Girl Guides, like Różyczka. It’s very effective; you create a powerful sense of the girl Rose living in a bubble.

EW: Recently I have learned about a book called How the Girl Guides Won the War. It has a chapter devoted to all the kinds of different activities the Girl Guides and Girl Scouts were doing throughout the world during World War II. American Girl Scouts were saving tinfoil; British Girl Guides were on patrol looking for flying bombs; and Polish Girl Guides were risking their lives acting as couriers and smuggling explosives for the Resistance.

DFB: I wonder if you could discuss

the themes of flight, poetry, and survival, which are all interrelated in Rose Under Fire.

DFB: I wonder if you could discuss

the themes of flight, poetry, and survival, which are all interrelated in Rose Under Fire.EW: I mentioned Micheline Maurel’s poetry; she felt that her ability to write poetry actually saved her life at Neubrandenburg, because she was taken up by a Czech girl who really, really loved poetry. The French were never allowed to get care packages, and a lot of the survival of prisoners depended on receiving such packages. Families sent them bread and sausages and cheese, but the French prisoners weren’t allowed to have any, and the Czechs were. It was all based on national borders and on how much at war you were with the Nazis and whether or not they considered you a race to be exterminated, and so on. The Dutch also, I believe, were allowed care packages; the Norwegians were spared having their heads shaved because they were so tall and blonde. So there were variations in the restrictions and treatment. Maurel’s Czech friend was getting regular supplies of extra food and shared it with Maurel in exchange for poetry, so I was very much aware going into writing this book that the ability to recite and compose poetry could actually save your life. That’s why I wanted Rose to write poetry, but also because I found Maurel’s poetry really moving. It was so much a part of the retelling of her experience that I wanted to use it in Rose Under Fire as well.

As for the metaphor of flight — Rose’s development as a poet is based partly on the fact that she’s a devotee of the work of Edna St. Vincent Millay, and some of her poems are quoted throughout the book. The epigraph is a very short Millay poem called “To a Young Poet,” and it’s about flight, so it seemed appropriate. Poetry, flight — that is what Rose does. And the sky! All the Ravensbrück prisoners say this: that the sky was the one thing that really represented freedom to them, because it was always changing; it was moving and dynamic. And of course there’s the end of the book where Rose is describing the principles of flight and she says that you have to have lift in your life; you have to be buoyed up by things; and sometimes you have to be thrust forward into new things…so there again you have the metaphor of flight.

A wall in Ravensbrück; the dynamic sky (symbol of freedom for the prisoners) above it.

A wall in Ravensbrück; the dynamic sky (symbol of freedom for the prisoners) above it.DFB: The association of flying and writing evokes the expression “flights of the imagination,” which implies relinquishing control and letting the mind soar. That’s how some people might think flying and writing are related — however, it seems that for you, a pilot, flying is not a matter of release and freedom but of close attention and intense focus.

EW: Yes, flying is hard for me. It doesn’t come naturally. I haven’t been doing it since I was twelve, like Rose; I’ve only been doing it since I was thirty-seven. I have to work at it. When I’m in the air I’m really, really concentrating on flying the plane.

DFB: The kind of poetry Rose writes is very tightly structured and has quite defined rhyme and rhythm patterns. So writing it would be a bit like flying a plane, with all its strict protocols and complicated instruments.

EW: Yes! Rose’s poetry — partly it is more tightly structured because she is writing it in 1944, and although some people were writing more unstructured poetry, she was raised on Edna St. Vincent Millay and Rupert Brooke. She quotes some William Carlos Williams, so she’s aware that there’s other stuff out there, and indeed a couple of her poems are free verse as well; but she’s clearly a bit of a traditionalist.

DFB: One of the elements I like in all your stories, and it’s especially noticeable in Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire, is how you don’t succumb to romance.

EW: I quite purposefully try to subvert that. There’s a lot of romance out there; we don’t have to read it all the time, as a steady diet. There are other aspects to the world. In Rose Under Fire in particular there’s a subverted romance. That again was driven by Micheline Maurel—she had a sweetheart who was an RAF pilot. She was in prison for two years, and the thought of her pilot helped sustain her. But he went and married someone else: after all, Maurel disappeared for two years, and he must have assumed she was dead. Not every whirlwind wartime romance ended happily; not everybody was committed to waiting. That’s what I was playing with there, but also I was playing with the question, Why should it all be about romance?

DFB: It focuses the story much more on female friendship and how it’s enduring and fundamental—instead of as a secondary theme to romance and adult life.

EW: You can come back to friendship. You can let it drop, for five years or ten years, and come back to it.

DFB: Another thing I’ve noticed is that none of your stories have magic in them. You write protagonists who are courageous and heroic in a very realistic world, which is different from the current trend that places child heroes in the realm of fantasy, where a magically endowed protagonist is often saving the world. What draws you to realistic heroism in this way?

EW: It’s very conscious. I am a big fan of Alan Garner and have been ever since I was four and my father read me The Weirdstone of Brisingamen — we used to live in the shadow of Alderley Edge. I had the art of Alan Garner with me as I was growing up, and of course much of his work was fantasy, but then he stopped writing fantasy and started writing books that just felt like fantasy. The Stone Book Quartet was a triumph of this. The four short novels have themes that feel like fantasy and moments that feel like magic happening through them — as when, in The Aimer Gate, young Robert Garner climbs up inside the church tower. He gets to the top of the spire and it’s dark, and he reaches up to the capping stone and feels letters carved there. He reads them with his fingertips in the pitch dark and realizes that it’s his own name. I thought it was so amazing that Alan Garner was able to keep this fantastical feel to his books and at the same time make them realistic. I very consciously set out to do that in my own writing, from the very first book that came out, The Winter Prince, to Code Name Verity and now Rose Under Fire. There’s magic in the world, and I want to make people aware of that.

From the May/June 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!