An Interview with Regina Hayes

A lifelong bookworm and unapologetic generalist, Regina Hayes, who led Viking Children’s Books from 1982 to 2012, has worked widely across genres in a career marked by intense curiosity; quiet, persistent daring; and a firm grasp of the world in which young people live.

A lifelong bookworm and unapologetic generalist, Regina Hayes, who led Viking Children’s Books from 1982 to 2012, has worked widely across genres in a career marked by intense curiosity; quiet, persistent daring; and a firm grasp of the world in which young people live. Hayes has also brought a refreshing spirit of irreverence to a field that, as she recalls of her first impressions of it going back to the 1960s, was still largely run by the “blue-haired ladies” of an earlier generation. Now editor-at-large at Viking, she continues to work with such authors as Rosemary Wells, Sarah Dessen, Laurie Halse Anderson, Jonathan London, and Elizabeth George. Our conversation was recorded at Hayes’s office in New York City on September 20, 2017.

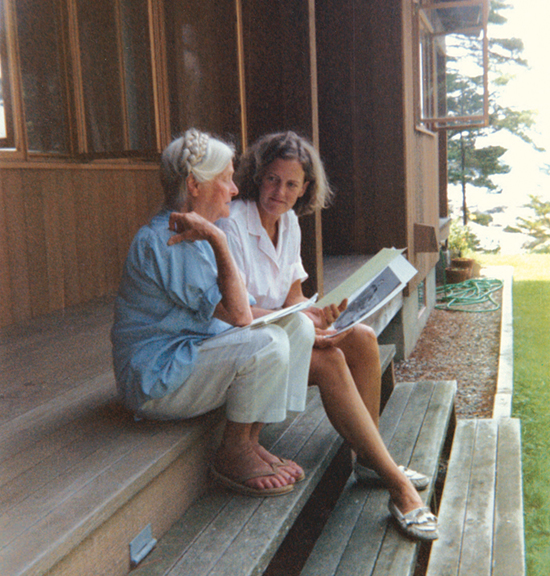

Photo: Mark Zelinksy.

Photo: Mark Zelinksy.Leonard S. Marcus: What led you to work in children’s book publishing?

Regina Hayes: I had spent my entire childhood doing nothing but reading. I was one of those kids to whom people would always say, “Get your head out of a book!” I didn’t really go outside and play because I was asthmatic and I spent a lot of time in bed, which is how they treated it then. I read my way through the entire library, and of course read a number of my parents’ books, too. But oddly enough, I never thought of publishing as a career. After college, I spent two years in Paris, working as an au pair, giving English lessons, and going to school. When I came back, totally broke, I started working for a temp agency. They sent me to places like Standard Oil to do statistical typing, and the American Bankers Association — misery. And then they sent me to Putnam, to work for the publicity director. I walked in there, and I was like, “Oh, wow!” There were piles of books everywhere. Nobody went home at five o’clock. Nobody even noticed it was five o’clock, they were so engrossed in their work. I met this young woman who said, “You should apply for my job. I’m quitting next week.” I said, “Oh, what do you do?” “I work for the children’s editor.” I thought, Hmm. That sounds good. You read manuscripts and such, do secretarial work. So I applied for the job and got it, and I fell in love instantly. It was just, as they say, the key fitting the lock. I would have done it for free, and I practically did.

LSM: That was in 1966?

RH: Yes, that’s how it began. And then I got promoted, step by step — I was no instant success. I was an assistant editor, then an associate editor, and finally an editor. It was the Johnson administration era of Title II money for school and library book purchases, so my first books were series: the Colby books, which were collections of public-domain photographs turned into books — Fighting Ships of World War II, Tanks of Our Army, things like that, and also a series called the Challenge books. I worked under Alice Torrey, who was editor in chief of Coward-McCann [an imprint of Putnam]. Alice published Astrid Lindgren’s Tomten books, and Jean Fritz was another of her authors. Margaret Frith was senior editor, and I learned a lot from her, too.

LSM: How would you compare Coward-McCann in those days with the competition?

RH: It was the era of the blue-haired ladies. At the time, I had no sense of the larger field, but we didn’t have a lot of award winners certainly.

LSM: As a young person of the 1960s, were you surprised to find that publishing was still so hidebound?

RH: Well, publishing for children was very much oriented toward the school and library market. It was about cultivating the gatekeepers. We didn’t think about marketing to the immediate audience, the children.

LSM: What was the first book you edited?

RH: An easy reader called The Clay Pot Boy [by Cynthia Jameson, 1973]. I hired Arnold Lobel to illustrate it. I couldn’t believe he agreed to do it. What I mostly remember from that era, though, was meeting James Marshall. He came into the office with his portfolio, and it was a revelation to me that books could be so witty and fresh, so interesting to an adult as well as a child. We talked for hours. That was shortly before I left Putnam. It was right about then that Alice retired and Ferd Monjo took over.

RH: An easy reader called The Clay Pot Boy [by Cynthia Jameson, 1973]. I hired Arnold Lobel to illustrate it. I couldn’t believe he agreed to do it. What I mostly remember from that era, though, was meeting James Marshall. He came into the office with his portfolio, and it was a revelation to me that books could be so witty and fresh, so interesting to an adult as well as a child. We talked for hours. That was shortly before I left Putnam. It was right about then that Alice retired and Ferd Monjo took over.LSM: What did you learn from Alice about being a children’s book editor?

RH: She had a gravelly voice, and would say, “Darling, I never want to hear the word cute.” She had a very unsentimental view of children’s literature. She was definitely a character. Alice wrote very long letters. She would use a Dictaphone, and then she would depart for the country at noon on Friday, leaving me all these letters to type. When I was a little more confident, I began to edit them ruthlessly. I would cut to the chase! Thank God she never noticed.

LSM: How did it happen that you went over to Dial?

RH: To be perfectly frank, Ferd and I were not a particularly good match. I went for an interview with Phyllis [Fogelman], and we quite hit it off. She said to me this funny thing: “I’ve interviewed a lot of people with more experience, but what strikes me about you is that you really love books.” Which I thought was interesting because I can’t imagine anybody would be in this field if they didn’t love books!

LSM: That was a good beginning.

RH: Phyllis had very high standards, and she was certainly aided and abetted and encouraged by Atha [Tehon], who was her art director. Dial’s standards for art and production were so high. At Coward-McCann, we did not have an art director. We’d freelance jackets, and we did our own design. For chapter heads, you got out the type book and some tracing paper and you figured it out. Atha almost fainted in horror when I told her that. She was so rigorous, and she had exquisite taste. She could not be hurried. Even Phyllis did not dare try to hurry her.

LSM: Phyllis was passionately committed to the civil rights movement, long before most of her colleagues.

RH: Yes, and she made that commitment her personal stamp, something that defined her list. She was determined to publish books by African American authors and artists and do it really well. And she did.

LSM: You worked with Mildred D. Taylor on Song of the Trees after she won the Council on Interracial Books writing contest.

LSM: You worked with Mildred D. Taylor on Song of the Trees after she won the Council on Interracial Books writing contest.RH: After winning the prize, which came with the promise of publication, Mildred went around and interviewed various publishers, and we were fortunate that she chose us. Mildred was a beautiful writer, but she had a weakness for flowery language. We focused on the importance of plot: your audience is ten years old; they’re not interested in lengthy descriptions of trees and so forth. Then her next book was Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.

LSM: How did you come to be the editor for Mildred’s books, rather than Phyllis?

RH: Well, Phyllis had a pretty heavy load. She was already editing Julius Lester and Tom Feelings, among others. She just adored Tom and encouraged him so much. His Middle Passage took years and years. Every time I would run into him, I would ask, “Tom, how’s the book coming?” “Oh, I’ll have it finished,” he would say. But each time, he would tell me he had finished less of it than the last time I’d asked. He did ultimately finish it, of course, and beautifully.

So after Mildred’s first book, I was the one who had the relationship with her. Working with her was a lengthy process, with many drafts. Mildred often spelled things out a little too much, and we went back and forth about it: “You don’t have to say the father had set the field on fire. It’s very clear that he set the field on fire.” But she was very receptive.

LSM: Roll of Thunder is a magnificent book.

RH: Yes, it’s very powerful. I remember when it came in — it sounds ridiculous — but I got this tingle. “Can this really be as good as I think it is?” Then other people read it, and we all thought it had award potential, but you never know. It’s kind of a crapshoot. It was pretty exciting when she won the Newbery.

LSM: Did you find yourself gravitating toward fiction?

RH: I never specialized. I did a fair amount of nonfiction, which I liked, although for nonfiction you have to be able to give tremendous attention to detail. It’s a much longer process to edit a nonfiction book than a novel. And I also loved picture books. At Dial, I was reunited with Jim Marshall because Phyllis signed something up by him. He mentioned that he knew me, so I ended up working with him there, for instance on Space Case and I Will Not Go to Market Today. But the books we did together that I think of as having the greatest staying power are Jim’s Fox series of easy readers. I’ve read them with my grandchildren, and they adore them and find them hilarious. The humor is still just as fresh and relevant.

RH: I never specialized. I did a fair amount of nonfiction, which I liked, although for nonfiction you have to be able to give tremendous attention to detail. It’s a much longer process to edit a nonfiction book than a novel. And I also loved picture books. At Dial, I was reunited with Jim Marshall because Phyllis signed something up by him. He mentioned that he knew me, so I ended up working with him there, for instance on Space Case and I Will Not Go to Market Today. But the books we did together that I think of as having the greatest staying power are Jim’s Fox series of easy readers. I’ve read them with my grandchildren, and they adore them and find them hilarious. The humor is still just as fresh and relevant.LSM: Fox is a likable yet disreputable character.

RH: Yes, exactly — and he’s totally representative of Jim. Fox has that sort of grandiosity, and is constantly being deflated. Jim and I became very good friends. We were almost exactly the same age, and we celebrated birthdays together. He and his partner Billy would come to visit. My family and I all just adored Jim.

LSM: You told me a story once about being at a restaurant with Jim — something to do with a shoe.

RH: It was actually [Dial editor] Toby Sherry who was with him that time, and she dined out on that anecdote for many years. Jim was with his elderly father, and they had hailed a taxi and were about to get in when this woman pushed past them and grabbed the taxi and it drove away. Sometime later, Jim realized he was sitting next to the same woman in a different restaurant. She had taken her shoes off under the table, so he pretended he had dropped something, stole one of her shoes, put it in his portfolio, and left. Whether that was entirely true, I don’t know, because he could always make up a good story.

LSM: Did his books require much work?

RH: A fair amount. We’d go back and forth. The first Easy-to-Read we worked on together was Three by the Sea. He learned a tremendous amount from that experience, and he went on to become a really good easy-reader writer, and you know how hard that is. People think writing an easy reader is simple. It’s not. It’s one of the hardest things. Some people have a knack for it, and some people don’t. Jim did. [See also “An Easy Reader Renaissance” in this issue.]

LSM: Who else did Phyllis work with?

RH: Rosemary Wells, of course, and some of her best books were done at Dial. Morris’s Disappearing Bag, for instance. Dial is also where Max & Ruby started as a series of board books.

LSM: Those were pretty revolutionary.

RH: Yes. “Very First Books,” they were called. I was quite involved with them too. Dial was a small enough place that everybody was involved in everything.

LSM: Up until that time, the perceived market for baby and toddler books was extremely limited, wasn’t it?

RH: I can remember one reviewer, who shall remain nameless, saying these books were too good, that they had too much content. Which was ridiculous. But up until then baby books were all based on super-simple concepts, whereas the Max books actually had tiny little plots, as much as could be done in six spreads.

RH: I can remember one reviewer, who shall remain nameless, saying these books were too good, that they had too much content. Which was ridiculous. But up until then baby books were all based on super-simple concepts, whereas the Max books actually had tiny little plots, as much as could be done in six spreads.LSM: Retail was becoming a bigger portion of the market.

RH: Yes. This was around the time of the rise of the independent children’s bookstore. At one point the Association of Booksellers for Children had four hundred members. It definitely had a huge influence: for the first time, children’s booksellers were demanding books they could sell directly to the parents as opposed to the librarians who set the standards and whose recommended lists were kind of a bible. By then I had two children of my own, and I realized more and more that they would look once at some of these beautiful picture books that I would bring home, but never again. The ones they wanted over and over — for example, the ones by Verna Aardema like Who’s in Rabbit’s House? and of course Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears — made me realize the importance of a read-aloud text. Picture books are not just portfolios of wonderful illustrations.

LSM: In the previous generation, by and large, editors didn’t have children.

RH: No they didn’t, and in fact when I had mine I didn’t know anyone else in the field with children at home. Then one of the copyeditors gave birth and I remember asking her: “How do you make it work? What do you do?” She was like, “Well, you have to get” — we didn’t call them nannies then — “you have to get a babysitter.” Now it’s so common, and we bend over backward to make it work for our staff.

LSM: Were you still at Dial when its children’s book division was purchased by E. P. Dutton?

RH: No, but it was very close, because by then I had been interviewing for the Viking job. Right around the time I had my second interview, Phyllis called us in and told us that Doubleday [Dial’s parent company] wanted to sell us off to someone, and that she was interviewing possible suitors. And then a week later I was offered the Viking job, so it looked like I was jumping ship, but in fact I had already had two interviews.

LSM: In your experience, did the process of acquiring books change significantly as publishers started to become larger corporate entities?

RH: At Dial we were sheltered from it, because Phyllis took care of all that. It was pretty simple, actually, the process of acquiring books. Nobody above us at Dial cared that much about the children’s books because nobody had yet woken up to their potential profitability. At Viking there was quite a different attitude, because children’s books had always been a profitable part of the company.

LSM: At Viking, you became the caretaker of a venerable list of classics, and in some cases — Robert McCloskey for example — the artists themselves were still alive. Did you try to persuade the creator of Make Way for Ducklings to come out of retirement and publish another book?

LSM: At Viking, you became the caretaker of a venerable list of classics, and in some cases — Robert McCloskey for example — the artists themselves were still alive. Did you try to persuade the creator of Make Way for Ducklings to come out of retirement and publish another book?RH: I did, and Bob started a memoir, but he wasn’t able to finish it. I knew him quite well. One time we were supposed to meet for dinner on the night before an ABA [American Booksellers Association convention, forerunner of BookExpo America] speaking engagement. I am sitting in the hotel lobby, waiting, and it turns out Bob has gone to the wrong hotel. He finally shows up wearing this ratty old sweater, and he has lost his luggage. Luckily there is a gift shop in the hotel, so we buy him some socks and a shirt, and I think underwear, too. The next morning he’s got on the new shirt, but he’s wearing the ratty old sweater over it. He’s like, “I can’t stand up in front of all those people with nothing but a shirt between me and them.” He of course charmed everybody.

One of the things I am proudest of having done at Viking is restoring those “golden oldies,” as we called them, to their former splendor. At some point in the 1970s — as an economy measure — they had taken the jackets off, and the books had these covers that were printed on Tyvek. Remember Tyvek? They were just terrible looking. For Puffin, they had reduced the Madeline books and Make Way for Ducklings to a 7x9 trim that was completely wrong, cropped the art, and so forth. Bit by bit I put jackets back on them, and made sure they were re-originated if the art had become faded and awful looking. We did that with Madeline, and the Ezra Jack Keats titles, and of course the McCloskey books, Corduroy and the other Freemans. All the signature Viking titles. The other thing I was happy about is that when we had the opportunity to bring all the Keats books under our roof, we did so.

LSM: What you were doing was very timely in that as the retail market continued to grow there were more and more parents who didn’t know what to buy for their children and were happy to reach for a “classic” they recognized.

RH: Yes, and at the chain stores, which were growing by leaps and bounds, the books had to sell themselves. They had to look good. What were you saving by not putting the jacket on them? It just cheapened the look of them. If a book already costs fifteen dollars and it’s going to cost sixteen dollars with a jacket, you’re well advised to put the jacket on and make it look like something of value, a beautiful object.

LSM: Related to this, more and more crossover books were being published in the 1970s and 1980s, illustrated books with a potential adult as well as child readership — David Macaulay’s Cathedral, for instance.

RH: The Macaulay books are a perfect example.

LSM: Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith’s picture books were very popular with college kids, weren’t they?

RH: Yes, although that certainly wasn’t our intent. We just thought they were funny. Lane, this thin, shy young man, came in with his portfolio of really astonishing artwork, but I didn’t have anything for him at the time. It required a particular type of manuscript. And he said, “Well, maybe you’d like this story my friend wrote.” And he pulled out Jon’s manuscript, which was then called “The Tale of A. Wolf,” and I loved it. I thought it was hilarious. We said we wanted to publish it, and somewhere along the line we agreed on the name The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs. Its success actually caught us somewhat by surprise — not me; I thought it was fantastic — but the sales department hadn’t gone crazy for it. I think we printed 15,000 copies, and wondered whether it should have been twelve. And then for a year we couldn’t catch up with it. It would be out of stock, out of stock, reprinting, reprinting. I think we reprinted something like six or seven times that first year. Within a year it was up over 80,000 copies, which for that time was huge. Stars were born. But it was also that Jon and Lane were very vigorous promoters. They traveled anywhere they were asked, and they were both so funny. They were a breath of fresh air, and they won themselves many fans among teachers, librarians, and booksellers. Then came The Stinky Cheese Man, and this time the surprise was that it won a Caldecott Honor. Even our very seasoned library promotion director, Mimi Kayden, didn’t think it was the kind of book the committee would respond to. But the committee chair, Jane Botham, loved Jon and Lane. She really pushed for a funny book.

RH: Yes, although that certainly wasn’t our intent. We just thought they were funny. Lane, this thin, shy young man, came in with his portfolio of really astonishing artwork, but I didn’t have anything for him at the time. It required a particular type of manuscript. And he said, “Well, maybe you’d like this story my friend wrote.” And he pulled out Jon’s manuscript, which was then called “The Tale of A. Wolf,” and I loved it. I thought it was hilarious. We said we wanted to publish it, and somewhere along the line we agreed on the name The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs. Its success actually caught us somewhat by surprise — not me; I thought it was fantastic — but the sales department hadn’t gone crazy for it. I think we printed 15,000 copies, and wondered whether it should have been twelve. And then for a year we couldn’t catch up with it. It would be out of stock, out of stock, reprinting, reprinting. I think we reprinted something like six or seven times that first year. Within a year it was up over 80,000 copies, which for that time was huge. Stars were born. But it was also that Jon and Lane were very vigorous promoters. They traveled anywhere they were asked, and they were both so funny. They were a breath of fresh air, and they won themselves many fans among teachers, librarians, and booksellers. Then came The Stinky Cheese Man, and this time the surprise was that it won a Caldecott Honor. Even our very seasoned library promotion director, Mimi Kayden, didn’t think it was the kind of book the committee would respond to. But the committee chair, Jane Botham, loved Jon and Lane. She really pushed for a funny book.LSM: One of the major impacts of that book had to do with its innovative use of type.

RH: We did have a set-to about that when it came in. They had gone so close to the edge of the page that some of the words were cut in half. I said we can’t do that because there’s no way we can guarantee that this will be trimmed exactly. I think it was Jon’s wife, Jeri, who redid all the layouts over a weekend to give us more breathing room. Big, small, big and small on the same page, big dwindling down to small. They had so many ideas. All those jokes with the front matter and the flaps. They were very, very inventive.

LSM: Did you question whether a six-year-old would get the jokes?

RH: I didn’t think it was necessarily for a six-year-old, but that it might be for a slightly older picture book reader. At the time I thought you probably needed to know the original stories to get the jokes, but now I’m not so sure that’s true, having read the book aloud innumerable times. Jon’s versions are funny in themselves.

LSM: When you think of the child appeal of a Robert McCloskey story and that of a story by Jon Sciezska and Lane Smith, it’s as though the books have come from two very dissimilar worlds. It’s curious that such different books can somehow coexist.

RH: It is interesting, isn’t it? The McCloskey books continue to resonate. There’s just so much heart, so much sincerity to them. The stories all have to do with finding home, being safe, that sort of thing. Jon and Lane’s books are more about parody, with a more sophisticated sensibility. Even so, their appeal is as much to the child as it is to the adult. You have to have that. You can’t just appeal to the adult.

LSM: Let’s talk about Barbara Cooney.

LSM: Let’s talk about Barbara Cooney.RH: Barbara’s niece Alice Frelinghuysen and I once went with Barbara to Hyde Park when she was working on her picture book Eleanor and wanted to research some of Eleanor Roosevelt’s letters. Barbara was also hoping she might have a chance to see Eleanor’s christening dress, and by a wild stroke of luck she managed to do so that day. That’s when Barbara said something that I have always remembered: “The author can just say, ‘The baby was christened in the parlor.’ The illustrator has to know who was holding the baby, what the baby was wearing, what the person holding the baby was wearing, what the room looked like, whether there were drapes, whether the minister was present and if so what he was wearing, and so on. The illustrator has to know all of it.” Barbara was great to work with. She was meticulous about her research. She would come in with these perfect little dummies. She loved our art director Barbara Hennessey, whom she would call “Little B.” Barbara Cooney herself was “Big B,” although they were both pretty little! Barbara with her elaborate white braids and her bright blue eyes. She had such verve.

LSM: She was a strong writer, too.

RH: Yes, but it took her a long time. She labored over her drafts. Interestingly, Miss Rumphius outsells her Caldecott winners [Chanticleer and the Fox and Ox-Cart Man] by a lot.

LSM: I particularly like Hattie and the Wild Waves.

RH: She always said that Miss Rumphius, Hattie, and Island Boy, taken together, were as close to an autobiography as she would ever write. Hattie is kind of her mother’s story, but also hers. She came from a wealthy family, and I think she had to break away.

LSM: How about Simms Taback? Was he one of “your” artists?

RH: Yes, Simms was one of mine. The first book I did with him was There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly, which was really a redo of a little mass-market book he had published years before. I thought of it as a novelty book that we might publish without a jacket, at a lower price. But our sales rep said, “You shouldn’t do that. His art is amazing. You need to give it a proper showcase.” So that is what we did. Simms was such a perfectionist. He even designed the typeface. After that, he brought in Joseph Had a Little Overcoat, which was similar in format, and which of course went on to win the Caldecott Medal.

LSM: You have been equally committed to fiction writers, for instance Sarah Dessen.

RH: Sarah and I have worked together on her last nine books, and we have published all of her novels in paperback. We have had a good time together. I love her books because they are contemporary and because she creates a whole world. Even her secondary characters are all so fully realized. Revisions always have to do with structure or plot, never with the writing itself. Sarah’s writing just doesn’t need editing. Once and for All is one of those books that came together effortlessly — at least on my part. Sarah claims she struggled with it, but it reads like a book that just poured out of her.

RH: Sarah and I have worked together on her last nine books, and we have published all of her novels in paperback. We have had a good time together. I love her books because they are contemporary and because she creates a whole world. Even her secondary characters are all so fully realized. Revisions always have to do with structure or plot, never with the writing itself. Sarah’s writing just doesn’t need editing. Once and for All is one of those books that came together effortlessly — at least on my part. Sarah claims she struggled with it, but it reads like a book that just poured out of her.LSM: At Viking you headed a department for the first time. What did you need to learn in order to do the job well?

RH: I had to learn how to put together a balanced list, one that didn’t just reflect my own tastes. What’s great is that once you assemble a group of editors whose taste you trust, you have to trust them, even if you don’t particularly see the value in something. I certainly have been wrong many a time.

LSM: Can you give an example of a book that you have published but might not yourself have chosen?

RH: When Deborah Brodie was here, she was very interested in publishing books of Jewish interest, so she published some picture books by Seymour Chwast that I wouldn’t have known to publish. She also did an excellent nonfiction series called Women of Our Time. Deborah had a nose for that type of young nonfiction. Later, when Jill Davis was here, she brought in Betsy Partridge. Jill had a talent for narrative nonfiction. Nancy Paulsen brought in Maira Kalman. I don’t know that I would have known to pursue Maira, but I love her books. Sharyn November was responsible for some of the fantasy we published. Fantasy is not my cup of tea, but Sharyn taught me an awful lot about it. She published urban fantasy, steampunk, all those different categories that I don’t know about, and she also liked the work of Nnedi Okorafor. Nnedi is an author whose moment has come! We’re publishing the second of the Akata Witch books [Akata Warrior], and George R. R. Martin has optioned one of her books for a series for HBO. She’s doing a Marvel comic. She’s doing adult books. She gave a TED talk in Tanzania! All of a sudden, there’s enormous buzz around her.

LSM: So far we have been speaking primarily about the responsibility you feel toward the writers and artists you publish. What about the publisher’s responsibility to children as readers?

RH: I think that we all as children’s publishers feel a special responsibility because we know we are reaching an audience that is so open. The children’s hearts and minds are open, which means that we can influence them. I think all of us hope that in the course of our careers we will publish a couple of books that have a real impact. For example, children are so aware of unfairness. I can remember reading Mildred D. Taylor’s The Friendship aloud to my son, and he was just so — “What? No! That’s not fair!” You can help kids to recognize injustice early on, and in so doing you can make a difference. All of Mildred’s books have been incredibly influential in this way.

So has Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan. That little picture book packed so much into forty pages. And Sophie Blackall contributed tremendously with her illustrations, for example by depicting the mother sitting at the kitchen table in traditional dress while working away on her laptop. There it is: the whole clash of cultures. If you go to a party, you have to take your sister with you; but no, nobody does that here. The sibling rivalry and then the forgiveness at the end. It’s such a rich little story. It came out quietly, but ever since it’s just gotten more and more recognition. It was named one of the New York Public Library’s “100 Great Children’s Books in 100 Years,” among other honors.

So has Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan. That little picture book packed so much into forty pages. And Sophie Blackall contributed tremendously with her illustrations, for example by depicting the mother sitting at the kitchen table in traditional dress while working away on her laptop. There it is: the whole clash of cultures. If you go to a party, you have to take your sister with you; but no, nobody does that here. The sibling rivalry and then the forgiveness at the end. It’s such a rich little story. It came out quietly, but ever since it’s just gotten more and more recognition. It was named one of the New York Public Library’s “100 Great Children’s Books in 100 Years,” among other honors.LSM: Attention has focused recently not only on cultural diversity in books for young readers but also on cultural diversity at the publishing houses themselves. How are Viking and its parent company addressing the issue?

RH: Within the company, there’s a huge push for having a more diverse staff. Joanna Cárdenas has been doing a wonderful list of books with Latino writers, for instance Pablo Cartaya’s The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora and Celia C. Pérez’s The First Rule of Punk. At Putnam, Stacey Barney is doing great African American books. At Dial, Namrata Tripathi also does some really interesting books. The more that publishers are able to recruit editors of color, the more we’ll have a truly authentic list of diverse books, not just a bunch of white people sitting around trying for diversity.

LSM: When you consider how the business of publishing functions now as compared with how it worked when you were getting started, how do you weigh the pros and cons of “bigness” in publishing?

RH: Let me talk about the pros first. The support that you now get in marketing and sales is incomparable. When I started in the business, you basically threw a book out there, and other than trying to get it to the important librarians, marketing was pretty nonexistent. Now it’s a real powerhouse. When I sit in those meetings and they unveil the plans for, say, the new John Green novel, it’s absolutely overwhelming what they can do. Also, the way they are able to market directly to young people, particularly the YA audience. They’re out there with social media, all over the place. It’s a little harder with the middle-grade kids, because not all of them are on social media. How do you catch their interest? The cons — there are just so many books being published. We talk a lot about the issue of discoverability. How do you get people to know about the books?

LSM: But only a fraction of the total number of books being published get the kind of star treatment you just described.

RH: Absolutely. It’s all focused at the top. Though I will say we do have a school and library marketing arm, and they make a big effort to represent all the books, or as many as possible. But definitely the retail push is at the top. The first questions the sales department asks are: Is the author mediagenic? Does he or she have a platform? Not, Is it a good book? But, How can this person be utilized?

LSM: Finally, what exactly is an editor-at-large?

RH: After thirty years I was like, I cannot go to another meeting to talk about the future of publishing. I just can’t. All of the administrative stuff was killing me. It takes so much longer than it used to. I’m getting old. And also so much more is demanded. This new job has been a total joy, and to get back to just working on books — I love it. I couldn’t be happier. People were puzzled at first. They’d laugh and say, “She’s so…happy. Is Regina okay?” And I would think, Are you kidding me?

From the March/April 2018 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. For more, click the tag hbwomenshistory18 and follow the #kidlitwomen hashtag on Facebook and Twitter.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

jasmine torres

I just notice i use to read some of these books when I was little, their books are so interesting to read, I would not mind reading them again.Posted : Feb 14, 2019 03:08

Amy Kellman

Thankfully Regina is still editing, which means there will be more wonderful books.Posted : Mar 27, 2018 07:01

Debbie Reese

Back in the 1970s, Lotsee Patterson, a Comanche librarian, was a professor at U New Mexico. She was trying to improve library services to Pueblo Indian children. The usual method for such things is to bring in a bunch of white people. Not Lotsee. She knew how that would fail. History is replete with examples. She wrote a grant, got it funded, based on this idea: "it is easier and wiser to train Indian people in library skills than it is to take an outsider (non-Indian) and try to train them in a specific culture." That's what the publishing houses need to do. Training them in a culture not-their-own means they have to start by erasing all they think they know, because what they think they know is likely wrong. But can they admit that? Well, we've seen decades of books by people who think they know... and don't. Like Regina Hayes said... "a bunch of white people sitting around trying" isn't gonna do it.Posted : Mar 26, 2018 11:58

Cheryl Hudson

"The more that publishers are able to recruit editors of color, the more we’ll have a truly authentic list of diverse books, not just a bunch of white people sitting around trying for diversity." Thanks for these comments, Leonard and Regina. This is an excellent interview with insight into industry workings over a critical era in development of trade children's literature. #kweli2018 #wndb #blackhistorymonthPosted : Mar 26, 2018 09:21