Cherie Dimaline Talks with Roger

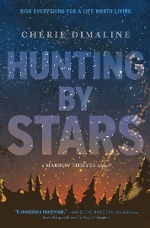

In The Marrow Thieves (DCB, 2017) and now its companion, Hunting by Stars, Canadian Métis writer Cherie Dimaline imagines an ecological catastrophe that has taken from most their ability to dream, a power retained by Indigenous people, who are now being hunted for their dream-making marrow.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

In The Marrow Thieves (DCB, 2017) and now its companion, Hunting by Stars, Canadian Métis writer Cherie Dimaline imagines an ecological catastrophe that has taken from most their ability to dream, a power retained by Indigenous people, who are now being hunted for their dream-making marrow.

Roger Sutton: What did you dream about last night?

Cherie Dimaline: I had a very strange dream. I was wandering through a city that I assumed to be in Europe, but it turned out to be somewhere in the southern U.S. I was trying to find my way into a building, because apparently I lived there. There were a lot of strange people around who I did not recognize.

Cherie Dimaline: I had a very strange dream. I was wandering through a city that I assumed to be in Europe, but it turned out to be somewhere in the southern U.S. I was trying to find my way into a building, because apparently I lived there. There were a lot of strange people around who I did not recognize.

RS: I think we need dreams, and clearly you do too.

CD: Absolutely. When I started writing about dreams for the first book [The Marrow Thieves] I learned about the science behind them, oneirology, the study of dreams. We really can’t process our thoughts without that secondary layer of dreams — I hadn’t realized that. We literally need that safe space within ourselves to be able to process life. What a great metaphor for holding onto hope.

RS: It was so interesting to me that you really have one fantastical element, which is the marrow’s role in creating dreams. But everything else is what I imagine, on my worst days, the world is going to be like in ten years.

CD: Yeah. I’d started off with the idea that this took place in the future. Continents are changing drastically; government policies are impacting vulnerable people. And every time I found myself going into schools to talk about the book, I felt kind of embarrassed that I was speaking as if this were some kind of dystopian future. I began introducing the idea of the story as something kids would be very familiar with. None of it would sound out of place, but this was my imagining of events.

RS: It didn’t feel that far away at all, which is to your credit. Even those scary Karens at the end.

CD: Yes, the scary Karens were definitely my take on things. Up here in Canada, watching what was happening in the States with Trump and the Capitol building, hearing some of those statements that were being made. And then the shock that people seemed to have about the place of Republican women, what they were really saying, and how they were voting. I just couldn’t ignore that. Women are very influential. They’ve always been incredibly strong, but not all of them are saying the right things. It was a place to have a bit of levity, but I was really hard on those characters. They became almost caricatures. But I had to include them, because this is so evil, and I thought, Well, I’ll just lean into it and have some fun.

RS: What would you say is the core that began The Marrow Thieves?

CD: It was around the time in Canada when more Canadians were learning about the residential school system, where children were taken out of Indigenous communities and put into government-funded, largely church-run schools, in order to assimilate. A lot of those kids, we know, didn’t make it out. There were graveyards instead of playgrounds. It was just brutal. And it was very recent history. I mean, I’m forty-six and I have friends who went to residential schools. As the wider population in Canada began learning about what happened, there was an article in the national newspaper that asked a question: “Is this really genocide? Is genocide the right word to use? That seems too harsh; maybe we need to look at it as something else and stop calling it genocide.” They did this poll, putting out this question to Canadians: “Do you think it’s genocide?” People were voting. And it just pissed me off. It made me so angry. This is what we’re doing? We’re just having a polite conversation about whether or not it’s really that bad? Intergenerational policies of terror. So I sat down and started writing the book. The first emotion for it was anger, and a lot of frustration. Thankfully, as it went on and the characters developed, I realized that the bigger story was about relationships and success and Indigenous excellence and survival. But definitely, what got me started typing was anger.

RS: And where did the characters come from, French and Rose in particular?

CD: Like with many writers, they’re basically a collage of people I know. I see a lot of my cousins in there. I’m sure there’s some of me, although I need a therapist to recognize when I see myself in my work. Definitely it was people I grew up with, people I had known over the decades from different communities.

RS: How would you connect your books with your own reading, both as a young person and today?

CD: I read books that I don’t think were meant for me.

RS: Attagirl.

CD: My parents went out and bought me the books you’re supposed to buy, Nancy Drew and the classics. But I really gravitated toward authors like Stephen King, things that maybe a ten-year-old shouldn’t be reading. There was something I loved about an epic journey. How a person could get past terror and grow closer to community. Really, everything I was reading as a young person, a lot of horror novels, were about pushing through the terror to something better at the end. Not something big, like fantasy novels where you suddenly inherit a kingdom. It was just about being able to sit down in a moment of peace at the end of the day and how important that was. How big the small things were, how extraordinary the ordinary is. It’s also part of life in Indigenous communities — you get past all of that weight and all of that terror, and you come back to a place of community again. It’s so beautiful. It seems so small, but it’s so beautiful and precious. Reading those early books that were just labyrinths of sentences through fear and then you come to a simple place — it really inspired me to write that kind of story. Like a hero’s journey, but I guess a bit more realistic. It’s still dystopian, though, so I hope my books are not very realistic.

RS: It’s dystopian, but within our own world. Like in The Handmaid’s Tale — Margaret Atwood projected into the future, but in both cases (your books and her book) you feel that this could be happening here and now.

CD: I was talking to Atwood once, and she told me that she never writes anything that doesn’t already have precedent, that hasn’t happened at some point in history. An Indigenous publisher had asked me to write a short story in the apocalypse or dystopian genre, and when I sat down to think about it, I could not think of anything worse than what had already happened. It doesn’t make me a lesser writer to rely on the horrors of humanity for what I’m going to write. I just lean into it. And I do connect with readers in a much more real place, because it’s oddly and hauntingly familiar, which makes the book harder to put down or walk away from.

RS: Right. It’s not so much: How could this happen? It’s: How could this happen again?

CD: Exactly. I get asked what I want my readers to take away from the work. It’s none of my business what readers take away. I provide the story, and whatever they take out of it, that’s theirs. I don’t want to be prescriptive. I trust my readers. But if I’m being completely honest, this is exactly it, Roger: I want people to consider what happened and how we make sure it doesn’t happen again. I really want them to see these brilliant, beautiful, tough, broken Indigenous characters as people. To love the characters enough for readers to carry that love into their lives. You have walked with these characters. You have seen what they have been through. You understand the fact that they have a blueprint for surviving the apocalypse, because Indigenous people have already survived an apocalypse.

RS: When you take on a historical horror like the residential schools, how do you write a story based on that history without being exploitative? I remember when I was a kid, reading books about World War II. They were fun — escaping from Nazis. What a blast!

RS: When you take on a historical horror like the residential schools, how do you write a story based on that history without being exploitative? I remember when I was a kid, reading books about World War II. They were fun — escaping from Nazis. What a blast!

CD: I think about it every day. I’m going to use someone else’s words, the prolific Canadian Indigenous writer Drew Hayden Taylor. His family did not get taken to the residential schools. My family did not get taken to the residential schools. But I was on a panel once with Drew who said: “So many of us, in our work, touch upon that industry of boarding schools and residential schools. It is impossible to ignore or live outside of it, because residential schools were like a stone thrown into our pond, and those ripples impacted everyone. They impact the words we use; our understanding of our place in the country; our relationship to the government. They impact the language that’s left for us to relearn from people who’d tried to relearn and reclaim languages. They impact the ways we hold our stories and the ways we tell our stories.” So really, it’s all of us. I spent decades working in a community with people who survived the schools, and those whose relatives didn’t. I’m not going to speak for survivors or communities or families. I’m just going to tell the story that is very familiar to me, to move it forward.

Another great writer who’s a mentor, Lee Maracle, told me very early on that one of the responsibilities of a storyteller in the community is that you walk people into the darkness. You cannot ignore the darkness. But it is your job to always make sure that there is a way out, because you never know how vulnerable a reader or a listener is going to be. If you cannot provide a door that they can get through at the end of the darkness, you at least need to have a window to let the light in. I often think about that. I chose to examine this history and tell this story because at the time we weren’t having the bigger conversation that we’re having now about residential schools and their impact. And I’m going to try and always lead with Indigenous characters who are strong, who are familiar. They are the light.

Really, the story is about the weight of love, the unreasonableness of love, the ends that we will go to for each other. Again, the impetus was horror and history, but the real story is those relationships. The fact that we are still here. We still have each other, and we hold onto what we can. I didn’t want to write trauma porn, to be exploitative. But I can’t ignore the darkness. So if it’s there, I walk through it, holding onto the fact that I needed to bring light.

RS: And isn’t that what a story does? It brings order out of chaos.

CD: Absolutely. Stories are the nomenclature by which we categorize and understand our world. Stories are the language of truly understanding who we are, in this place, at this time. It’s like dreaming. It’s the way we process everything that’s swirling around us. My god, we are experiencing this pandemic, a new time of plague, and selfishly, I’m excited for the stories that are going to come out of it and that are already coming out of it. I know that they will help me process and really figure out the impacts on myself and on the world of what we’ve just survived.

RS: I think even with dreams, like the dream that you talked about having last night — they don’t really become anything until we tell it at least to ourselves in the morning.

CD: Yes.

RS: We give it language, at least in our heads, or for telling to our husband or whoever, but it’s a mess until it comes to consciousness and gets retold.

CD: One of the first gifts that we’re given in life is words. So much is accomplished in words. We connect. We engage with somebody to ask for what we need, to express what’s happening, to understand what we do and how to be. Words are the vessels that carry meaning for everything else. So a story is really incredibly powerful. I forget sometimes (and then I get angry with myself!), but I do like to keep paper by my bed, because I don’t want to lose the dreams. They start to dissipate quite quickly when you wake up, get the coffee, then wait, what was that again? There are stories I’ve written that have started with snippets of dreams. "So that came out of my own head, my own consciousness? Where? How did I get there?"

RS: Are you going to do a third book?

CD: I am. This wasn’t originally going to be a series. I wrote the first draft of The Marrow Thieves in six weeks, in that place of anger, while thinking No one’s even going to publish this book. I rewrote it many times, but thought it was going to go nowhere. And now, fast-forward four years later, it’s still on the Canadian bestseller list. It’s turned into this whole thing. I started to get letters and emails and petitions from young readers — they’ve even created social media accounts for the characters. Frenchie has an Instagram account, the characters are on Twitter. People were messaging me, being like, “What comes next?” They really, really wanted — and seemed to need — to know. I’d say no to a sequel, but then I understood I wasn’t capable of walking away. In my own head, I already had ideas of what happened to the characters I cared so much about. I’d have been fine with just leaving it, but I realized, “Okay, now I’m being selfish. I know what comes next, so I’ll write it out.” And then when I was drafting, I was like, “Oh, there’s going to be a third book.” And now I’ve learned, oh god, the third book has to be the conclusion. I know where I want to go with the story, and what that end note is. But, again, it’s about being honest and leaning into the darkness as well as the light, so it’s not going to be simple. I have to own the fact that we are still dealing with the repercussions of residential schools. There’s the difficult part. How do I — not solve this problem, but how do I do justice by this community?

RS: The resonances of the boarding school experience continue, but a story has to end. So how do you keep that ongoingness a part of the story while also giving it an ending? I had to laugh when you mentioned Frenchie’s Instagram, because that sounds like a Stephen King story. You write a novel, and then the characters pop up on social media and start threatening you.

CD: It’s kind of creepy, right?

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!