Joanna Ho and Caroline Kusin Pritchard Talk with Roger

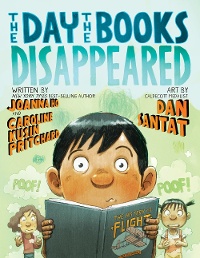

Arnold’s “all-time favorite thing to do” is read. Right on! His favorite thing to read about is airplanes. Right on again! But why don’t his classmates understand that their favorite thing to read about should be airplanes too? In The Day the Books Disappeared, co-authors Joanna Ho and Caroline Kusin Pritchard (aided by illustrator Dan Santat) take us into the misguided heart of the book banner.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Arnold’s “all-time favorite thing to do” is read. Right on! His favorite thing to read about is airplanes. Right on again! But why don’t his classmates understand that their favorite thing to read about should be airplanes too? In The Day the Books Disappeared, co-authors Joanna Ho and Caroline Kusin Pritchard (aided by illustrator Dan Santat) take us into the misguided heart of the book banner.

Roger Sutton: You two have a children’s lit podcast together, but this is your first collaboration on a book. What was the impetus for it?

Joanna Ho: Book banning. I was feeling very upset and angry. A lot of my books channel things I want to say about the world. Writing is a way for me to have a voice about things I feel are important. And so I started to write a book about book banning, and it was really, really, really horrendously bad. It was so very on the nose. It was just very bad — I don't know how else to say it. So I sent it to Caroline, who is brilliant at all things. We're such good friends that we can be very honest. She gave me some good feedback and I didn't know what to do with it, and then she had all these ideas: “What if you did this or this or this?” Her ideas inspired more ideas of mine, and then it was just: “I think we should do this together.”

Joanna Ho: Book banning. I was feeling very upset and angry. A lot of my books channel things I want to say about the world. Writing is a way for me to have a voice about things I feel are important. And so I started to write a book about book banning, and it was really, really, really horrendously bad. It was so very on the nose. It was just very bad — I don't know how else to say it. So I sent it to Caroline, who is brilliant at all things. We're such good friends that we can be very honest. She gave me some good feedback and I didn't know what to do with it, and then she had all these ideas: “What if you did this or this or this?” Her ideas inspired more ideas of mine, and then it was just: “I think we should do this together.”

Caroline Kusin Pritchard: I felt really sensitive and anxious because generally I love critiquing stories. It's one of my favorite ways to engage with the craft. But I feel like there are some really important boundaries. Whoever has written the story has their own vision and their own ideas, and your job is to support that space and ask questions and get a conversation going. But there was something about this story where I had no respect for boundaries. I was like, “Joanna, no. You need to name the kid Arnold and it needs to be in this room and we need to shift the plot.” Suddenly it wasn't “you,” it was “we.” I remember there was a moment of self-reflection, like, “Did I just throw myself onto this woman's vision?” But I think that's the gift of being as close as we are — we could cut through all the noise. And we knew we were homing in on something really good and true. So it just took off from there.

RS: So, obviously you both are anxious and angry about censorship, but how do you translate that into a book for young children so that it makes sense and is not too on the nose?

JH: Not by writing about it too on the nose!

CKP: I think in the original we had a bunch of book-banning adults storming into the room, right, Jo?

JH: Yeah, I’ve erased it from my memory.

CKP: Then, in our conversations, we were like, “Are we imagining the kids as these good savior types fighting against these grown-up bad guys? Is that the orientation we want for this story? Or is it more about recognizing that all these folks who are showing up at school board meetings were once children?” All these impulses to control what other people are doing had to start somewhere. And that's something kids can connect to. Maybe five-year-olds aren't sitting around existentially worrying about book banning the way we are. But the idea of different perspectives and the desire to be in control can resonate with them. And we got really interested in, “How can we find what those true emotional impulses are and show them in an accessible, funny, engaging, kid-centered way?” Jo, what do you think?

JH: Yeah, “How do we make it fun?” We landed on the idea of a child character with the magical power to “disappear” books, but we had a lot of conversations about how this maps to book banning. Like okay, there's an idea they don't agree with. There's some lived experience they don't understand. They just think their perspective or their opinion is better. They think that they're helping other people. We were trying to turn that into what it might look like for Arnold, the main character. And then similarly, how do we resolve it? For that, we thought, Well, he has to be able to step outside of his own opinion of what matters. For him it is his obsession with airplanes, which is actually very much based on my son. And so we tried to take our understanding, at the human emotional level, of how book banning happens, how we fight against book banning, and then convey that through the experiences of the kid characters and what it might look like in the classroom.

RS: I always wonder how we can talk about book banning without preaching to the converted. People like you, people like me, people like everybody I work with, we all instinctively understand why book banning is a terrible idea. But that's not true for everyone, obviously, because book banning is happening. How do we reach those people?

CKP: It's such a good question, and we grappled with that too. Are we going to want it so that Arnold disappears everyone's books but his own and then he has this aha moment that what he dreamed of is maybe not what he imagined, or what he expected. Or should we have it so that he disappears his own book accidentally as well?

RS: That was pretty smart, I thought.

CKP: Because we wish it was enough to say that the freedom to read is fundamental to a democracy, or that it’s essential for young kids to see themselves in books. The thing is that when you talk to like-minded folks, they say, “Yes, of course!” But the reality is there are a good number of folks who aren’t going to have that reaction. But the idea that maybe someone might come after their books, that maybe the Bible, say, might be banned, which it has been in certain districts — that might be an aha moment for them of Oh, wait. That might allow them to get the idea that books that may not be right for your kids may be right for someone else’s. And if you don’t want someone to ban yours, then maybe let’s take a step back from doing that to others.

JH: The sad truth is that often it doesn't hit people until it affects them personally. Like, “I have a child who's queer, and now my whole perspective on this issue has changed.” Otherwise, oftentimes people aren't that willing to change their mindset. So that was one reason, also, for having Arnold disappear his own book: “This eventually always circles back to impact you.” And I also think that so much change happens through relationships. You can scream all you want online, but it's not until you have some kind of trust in a relationship with another human and can have a human interaction — that's where change can happen in realistic ways.

RS: And I think we see in the book that the children in the class do like and respect one another, basically. So they are a community, right? This is something that's happening within a community, and it's up to the members of that community to get it fixed.

CKP: We had so much fun thinking about how to make each character feel well-rounded and true to kids but also allowing those relationships to show something that does ultimately lead back to what we hope kids can understand about book banning. So for example, one of Arnold’s friends is reading a book about tomatoes, and he's like, "Ew, tomatoes are disgusting." So in Arnold’s mind, it’s “How dare this friend? She doesn't know what's good for her, I do.” And that's all he can see. Ultimately when he sees his friend as a dear person with a full story and a perspective and a lived experience he doesn't share, he starts to realize, “Oh wait, that's not just about tomatoes. The tomatoes remind her of her grandmother.” That's what this attachment, the sentimentality, this connection is for her. Arnold comes to the realization of “I still don't like tomatoes, but I can see why she does.” And that understanding was really important for us to get at in a way that makes sense to kids.

CKP: We had so much fun thinking about how to make each character feel well-rounded and true to kids but also allowing those relationships to show something that does ultimately lead back to what we hope kids can understand about book banning. So for example, one of Arnold’s friends is reading a book about tomatoes, and he's like, "Ew, tomatoes are disgusting." So in Arnold’s mind, it’s “How dare this friend? She doesn't know what's good for her, I do.” And that's all he can see. Ultimately when he sees his friend as a dear person with a full story and a perspective and a lived experience he doesn't share, he starts to realize, “Oh wait, that's not just about tomatoes. The tomatoes remind her of her grandmother.” That's what this attachment, the sentimentality, this connection is for her. Arnold comes to the realization of “I still don't like tomatoes, but I can see why she does.” And that understanding was really important for us to get at in a way that makes sense to kids.

JH: I think there's two other things within that. One is this idea that the things that felt disparate and disconnected actually are connected — like the submarine and the plane, or the plane and the ostrich. We were intentional about choosing those seemingly random topics because another thing we wanted to show was that when you're banning books you think it's for this purpose, but actually all these ideas that you think you're against are connected to things that you are actually for. It's not so black and white.

RS: I thought you captured the conviction that children can have — that what they know to be true is the real thing. You’ve both had to argue with three-year-olds and five-year-olds and six-year-olds. It's not so much that they think your idea or your preference is stupid, it’s that their preference is unalterably correct. “Why can’t you see that, Mom?”

CKP: We went back and forth with each other and with our agents about Arnold and his likability in that way. Because when we see Arnold delight in being able to poof!, or ban, other kids’ books, there was this question of, maybe we’re coming on too strong. Maybe kids aren’t going to relate or he’s not going to be likable. And exactly as you said, if you’ve been around a three-year-old, they are going to tell you what’s what real fast. So we wanted to be able to capture that in a loving way and actually have Arnold be opinionated the way kids are and the way we want kids to be, right? We wanted him to be able to share his perspective but do it in a way that honors others too. We actually ended up leaning harder into that than we initially imagined, because it was a little tame at first. And to be honest, this book was not accepted by a ton of editors at first. It took us a while. We had to revise a million and one times. And part of the revision process was Arnold finding his voice in a way that was authentic and true but also gave him space to have his own meaningful character too.

JH: I think there's an aspect of Arnold feeling like he's helping other people. He's going to help them see that airplanes are the best. And that was also intentional — we think we're being altruistic when we're banning books. I think there's an aspect of, “We're helping other people, we're going to show them, we're going to force them to do what's best for them.” And then to Caroline’s point of realizing, “Actually, if I step outside of what I think is best, I can open my perspective and my world to better understand and humanize everyone else around me.”

CKP: Yes. I think you’re hitting on this idea, too, of scarcity and abundance. Arnold lives in a scarcity mindset. There can only be one thing that we should all focus on. There's only one right thing. So we wanted to show, ultimately, that we're sitting in this abundance of story and ideas and content and we’re living in this rich full world of story and that Arnold doesn't have to approve of or love all of it, but we're all better off for having all of it within reach.

RS: Children's book people like to think of ourselves as always being on the side of freedom and liberty and great books — but in my forty years in this business I've seen lots of big fights among the righteous about what is appropriate and permissible for children.

JH: I'm so curious from your perspective, Roger, as you see this cycle happening, does it feel like other cycles?

RS: No, this is worse. This is horrible. And what’s happening now that does not happen in the children’s book world, which is largely liberal and or progressive, is that these people who are censoring books now have the force of law behind them. Because they’re in power. When we fight among ourselves about J. K. Rowling in a children’s book chatroom and people get angry, it doesn’t matter, right? Because nobody on either side, or on one of the many sides of the J. K. Rowling question, had any power to stop anybody else from reading J. K. Rowling.

JH: That’s a really good point.

RS: And what we’re seeing now is that books are gleefully being removed from libraries.

CKP: Gleefully — and in the process, there’s such disrespect for librarians, teachers, and booksellers. We’ve historically recognized them as the ones who should be in charge of these decisions — curricular decisions, purchasing decisions — and we know this is their professional work, to be able to say what is and isn’t appropriate for certain grade levels or age groups. It’s so demoralizing to think that these individuals that show up at school board meetings think they know more than the people who have been educated in this work. That's one piece of this that was so hard to witness. These librarians, these booksellers, these educators are on the front line of protecting kids' right to read and maintaining diversity of books on their bookshelves — and their jobs are on the line. So Jo and Dan Santat and I decided to dedicate the book to them because of the risk they're taking to stick their necks out and to do what's right.

RS: I thought that Dan Santat’s pictures for the book really lightened up the whole thing too. And that’s part of what made Arnold likable. Dan clearly liked him. And I liked Arnold because he was a reader. And I understood his passion for planes, even if I didn’t share it. But he had a lot going for him. And the pictures helped keep all of those kids likable and real.

CKP: We felt exactly the same way. We were over the moon when we saw the illustrations. We had no chill. We were so excited.

RS: What is that like as a picture book author? You're done, you’ve signed off on your manuscript, it's gone away. And often you won't see art until maybe a year later, right? What's it like to come into contact again with your words as they've been interpreted by someone else visually?

JH: It's magical. When you’re starting in the industry, there's always so many questions about that. “How do you let go?” But once you experience it, it's so magical. I at this point don't want to talk to my illustrators at all, because it's amazing to see someone else interpret something I've written. And then not only understand it, hopefully in the way that I intended, but also add their own layers of meaning and their own experiences. And then of course they are magical humans because they have this ability to create amazing art. But to see it all come together and then to see layers that they've added, or humor that they’ve added, or whatever. It’s always the best day when you get that email saying, “We have art, we have interior, we have sketches. Stop everything and open the attachment.”

CKP: I feel like there’s not much else out there in the world where you have this true 50/50 collaboration. You’re creating such alchemy. You’re creating something from these totally different perspectives and you’re bringing them together. And there’s so much trust and respect in that process. And there’s something about having the patience to trust the illustrator, to dream up this world that started in your minds. I just feel like it’s — I love the word you used — magical. It feels like this magical, liminal space of waiting. Dan did something that probably took Jo and me ten passes before we picked up on it. As the book opens, the contents of the other kids’ books are represented by a lot of colorful scribbles. Just scribbles, because they’re of no interest to Arnold; he only cares about his airplanes. Then, at the end, when he’s come to care about other people’s perspectives, those scribbles have transformed into clear images of tomatoes and submarines and ostriches and the other topics the other kids are reading about. What a cool way to visualize the book’s theme! We were both like, "What? Dan, you're a genius." And of course, neither of us could have ever dreamt that up. No offense, Jo. Stuff like that is such a delight.

RS: And I imagine, too, that it’s so important having an editor who has worked with you on this manuscript and gone back and forth and really understands how you see what you've written. Because I can't think of a single author I’ve talked to about a movie adaptation of their book who was happy. And that's because the book has left the building, as it were. It's in other people's hands, whereas in publishing you’ve still got that same person, the editor, now in concert with an art director, working for you. It's like you’ve got your lawyers still in the room. I don't know, am I making this up?

JH: No, I think that’s really true. And I think the editor can often point an illustrator in a particular direction. Because we’re not in those conversations, I don’t know how far afield illustrators go in their interpretation. So in my experience it’s like, “Whoa everyone’s so brilliant, they totally understood what I was saying, and maybe there was some nudging along the way.”

RS: The editors are like, “My evil plan worked.”

CKP: I do think the editors are the keepers of the vision. They're protecting the vision and holding it a little bit loosely knowing that illustrators are going to take it in their own direction. But I’m sure the editors are steering the ship.

RS: Marcia Brown, in one of her Caldecott acceptance speeches, said the one thing illustrators have to remember is “in the beginning was the word” and that the text has primacy. I think we’ve probably all seen picture books that have gorgeous, gorgeous art. And it’s like, “Whoa, this text really is not doing anything, it’s all about the art in this book.” So it’s interesting to have a conversation about a picture book without the illustrator, with the authors of the text alone.

CKP: We had Dan on our podcast (Kidlit Happy Hour) right when we found out that he was attached to the project but it hadn't yet been announced. So we were giddy on that episode and we asked him, “What does it take for you to take on a project? I'm sure there are a million stories on your desk — why ours? Or why other ones that you say yes to?” He had such an interesting answer. He said that two things need to be in place for him. The first is that when he reads it, he can immediately get the visual. And he told us, “I read your story and I saw the kids in that classroom. I just knew him, I knew Arnold, I saw it, and I was excited to do it.” The second part is that he'll often think about issues in the world. Like Jo mentioned, she was thinking about book banning and feeling rage and sadness, and she found her voice through this story. That was the way she wanted to engage with those questions. And he says the same thing. He got our story and was like, “I was waiting for there to be a way for me to engage in this question around book banning in a way that was delightful, and not adulty, and not preachy, that felt good to read to kids.” And the second he felt those two things come together, he said it was really an easy yes for him, which was so gratifying for us to hear. As I said, we were giddy.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!