Jonathan Auxier Talks with Roger

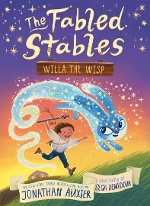

Jonathan Auxier says he needed a break after Sweep, so here we are with Willa the Wisp, the first volume in a projected series about the Fabled Stables, themselves inhabited by a number of unlikely and one-of-a-kind creatures — the Hippopotamouse, the Yawning Abyss — tended by young hero Auggie, himself attended by a Stick-in-the-Mud, and the whole shebang under the eye of the mysterious (indeed, unseen) Professor Cake.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Jonathan Auxier says he needed a break after Sweep, so here we are with Willa the Wisp, the first volume in a projected series about the Fabled Stables, themselves inhabited by a number of unlikely and one-of-a-kind creatures — the Hippopotamouse, the Yawning Abyss — tended by young hero Auggie, himself attended by a Stick-in-the-Mud, and the whole shebang under the eye of the mysterious (indeed, unseen) Professor Cake.

Roger Sutton: Why don’t you tell me from whence this descent into the Augean stables?

Jonathan Auxier: I appreciate the reference! The Fabled Stables is a major shift from everything that I’ve written, but in some ways it feels truer to who I’ve always been as a reader and as a person. My other books tend to be kind of heavy, and there’s a lot of research — but the main reason I love writing is play. I wanted to take a break after writing Sweep to cleanse my palate and re-discover that sense of play.

Jonathan Auxier: I appreciate the reference! The Fabled Stables is a major shift from everything that I’ve written, but in some ways it feels truer to who I’ve always been as a reader and as a person. My other books tend to be kind of heavy, and there’s a lot of research — but the main reason I love writing is play. I wanted to take a break after writing Sweep to cleanse my palate and re-discover that sense of play.

RS: Are all the beasts sentient, or just the ones that Auggie meets?

JA: I am quite fast and loose with that (though the third book has now been finished, and all of them are more or less sentient). But I would say there’s a sliding scale, depending on what makes the story and the moment the most fun. As people who love animals would attest, all animals are more sentient than we give them credit for. They have more emotional depth and are more responsive to their environment.

RS: Tell me about bestiaries.

JA: I’ve spent my whole life reading them, ever since I was very young. These compendiums of beasts — the older back you go, the more fantastical they are. I always liked Samuel Johnson’s depiction of a rhinoceros, with the “saurus” on the end being really appropriate, because it looks like something from the prehistoric period. Bestiaries are some of the earliest illustrated books, and they are sort of a perfect nexus for the fusion between magic and science. Sophie Quire and the Last Storyguard was a book where I dug extremely deeply into the world of ancient bestiaries. Some of them I worked into the book, but what was more fun was making my own beasts that had the spirit of those old bestiaries but also involved a little bit of wordplay or something like that. I loved doing that in Sophie, and I wanted the Fabled Stables to be a place where I could continue to come up with silly, strange, one-of-a-kind beasts. The series is not full of canonical monsters — we’re not going to be finding griffins and unicorns. All of the beasts have their own twists and their own specific identities.

RS: You’ve really given yourself an opening for an open ended series here, because whenever a new creature appears, it creates its own stable. You sly dog.

JA: There’s never a real-estate problem. The stables themselves are a magical space, alive and unpredictable.

RS: Unstable, as it were.

JA: The island that Auggie’s stables are on continues to expand in my imagination. There’s a lot going on underneath this series that for me, as a storyteller, is really exciting, and hopefully my excitement translates for the reader.

RS: It gives you a reason to do it, right?

JA: Absolutely. And another, more practical reason had to do with my own experience as a parent. I usually write pretty complicated upper-middle-grade books. But I have three daughters who are much younger, and they kept asking me to write something they could read. I am very picky about what I write, so I was like, “When an idea comes, I’ll get to it.” However, it occurred to me that could be fifteen years from now, at which point my children won’t care.

RS: What’s the age difference?

JA: They’re each two years apart, and when we do a read-aloud, we need to find books that appeal to all three of them. That’s an incredibly difficult task. The youngest kid needs the picture-book experience, with a full-color illustration on every page, constant page turns — that’s necessary; but the oldest kid deserves a larger, more complicated story, with slightly different themes. There aren’t a lot of books that do that, that appeal to a broad spectrum of readers between the ages of three and eight or nine (I can think of two: the Princess in Black books and Mercy Watson). Instead, we jump to chapter books, which have a much higher word count; or early readers, which have simple language. Really, what I wanted was a novel-like picture book that could be read aloud in a single sitting. One hundred pages, illustrations on every page, a low word count, but a more complicated vocabulary and story. I realized maybe this little boy and his stable, which have been rattling around in my head, could be the type of book I as a parent was looking for.

RS: Let me argue with you a bit. On the basis of just reading aloud, not reading level, you could read those same three kids Little House in the Big Woods. What’s the difference?

JA: The difference is you still are losing the very young child, who needs a new picture every thirty seconds. Once they all age up to a point, you absolutely can. My daughters are now getting to the point where they will all sit through books that are not as heavily illustrated.

RS: What are they right now, just for reference?

JA: Right now they are four, six, and eight. But I started this when they were two, four, and six. I’ve hand-sold dozens of copies of The Princess in Black on that pitch alone: one book to rule them all. A whole bedtime in one book. That’s really appealing to a tired parent who still wants to have a good, exciting, fun read-aloud experience.

RS: I speak from personal experience here, I think, but does your oldest child feel resentful about being seen as part of the same audience as your youngest?

JA: I don’t think so. I suppose some kids would feel that way, but we live in a new age. When I was growing up, you really identified by your subgroup, stridently. You learned a lot about a person by what music they hated, or what genres. The sci-fi kid and the fantasy kid used to be like the Jets and the Sharks, which is almost impossible to fathom today. My older daughter is reading the second or third Rick Riordan series, but she also reads comics and picture books every night. There’s no sense of shame. Her identity is not attached to what she’s reading. If a story compels her, she is completely in. That could change — I could be naive. A year from now, she might put her foot down.

RS: Do you have a family read-aloud tradition in your home?

JA: Oh, absolutely. I doubt you could meet a writer with kids who doesn’t put that at the center of their parenting. Though I’m very straightforward about how exhausting that can be.

RS: I bet.

JA: So, I wanted this series to be a gift to parents. “This is the one book that we’re reading tonight.” It’s long enough to be a full meal; it satisfies everyone story-wise. None of this “just one more!” Especially now, when parents are basically captive in their own homes with their children, the ability to say this was a full experience, beginning, middle, end. It was bigger than one or two shorter picture books. Because kids want that length of time. For me, this was a way to get them both. It’s satisfying to the kid, and also contained for the parent.

RS: How, physically, do you do these read-alouds? Are you all gathered together on a sofa?

JA: Our youngest has now gotten to a point where she will sit through longer books because she knows it forestalls bedtime. We have a very specific ritual — I’m very fidgety, so we have an entire drawer of different colors of Silly Putty, trays with little toys and trinkets you can shove into the Silly Putty.

RS: Or your nose.

JA: They each have their own fidget thing, and we read every single night on the bed. It’s become a full family affair, where even the parent who’s technically off-duty sits in the room and hears the story. There’s a lot of juggling right now — with three children and only two parents, most of our lives are zone defense. It’s nice to have one half-hour every night where we are all in the same room, sharing a single experience.

RS: I imagine it’s hard to keep a sense of distinct rituals at a time when we’re all spending so much time together.

JA: Absolutely, but right now rituals are the only things keeping my home working. The more you can rely on those, the more you can guarantee the space for meaning and significance in your day. If I allow everything just to surprise me as it comes, then I’m never really present in the moment. For me, the need for that has been greater than it’s ever been. We’ve added more rituals, because I think those are a better way to manage things and create unity than just aggressive scheduling.

RS: Do you feel like Professor Cake there, masterminding the evenings? I’m really curious about him.

RS: Do you feel like Professor Cake there, masterminding the evenings? I’m really curious about him.

JA: I am also deeply curious about Professor Cake. Children’s literature is not wanting for mysterious, slightly magical professor characters who seem to know more about the story than the heroes.

RS: He’s like Conchis in The Magus. Did you ever read the John Fowles novel?

JA: No. I’ve got to check that out. I’m always looking for antecedents to character type. Professor Cake is who I keep coming back to, because he’s a nexus for a lot of childhood experience. Childhood is so much about contending with powerful authorities who do things we don’t always understand, and who ask things of us that we don’t necessarily want to do. There’s so much trust — and apprehension — in trusting someone like that.

RS: Sounds like religion.

JA: The defining experience of childhood is stepping out of a childlike wonder into a different threshold. The age-old debate between faith and reason, or magic and science — all of that is really just metaphor for being forced to step out of childhood. This is why I don’t ever get tired of children’s books, and what I really love are stories about the end of childhood. That threshold, where you are leaving something behind, and it hurts, but you need to move forward — that never ends. Your last day at home before you go off to college. Your last day as a student before you enter the working world. Your last day as a single person before you’re married. We are always leaving behind something beautiful to move toward something unknown, straight up till the final breath we take. Children’s literature that deals with that sensitively and smartly and artfully never loses its resonance to the universal human experience. Those are the books that still speak to me as a thirty-nine-year-old adult.

RS: How do you think that the Fabled Stables would have spoken to you as a kid?

JA: I’ve always been obsessed with language and wordplay. Almost every story I write starts with a pun, sometimes embarrassingly, because it can be a silly, dumb pun, and I’ve just made this huge story around it.

RS: I once had to tell Norton Juster I never read The Phantom Tollbooth, because I’m the opposite of that kind of kid.

JA: That book was just like candy to me. I adored it. As a kid and a reader, I was desperate to uncover the personality of the storyteller. I think of the writers I was obsessed with, Roald Dahl or Shel Silverstein — what was really powerful was I felt, by the end of several of their books, that I knew the personalities creating the stories. Of course, I have learned as an adult that both of those men were much more complicated and less child-friendly than I thought. But the storyteller behind them felt like a real person, and somehow that was related to how they played with language.

RS: Do you like the illustrations?

JA: As a six-year-old boy, I would have been absolutely blown away by Olga Demidova’s stunning art. We are so lucky to have her in building this world. The books don’t work just as text alone — her art is what makes them come alive. But my hope is — and I’ve seen this happen with young readers already, and I think this would have happened with me — kids who’ve read the first Fabled Stables book, Willa the Wisp, spend the rest of the afternoon coming up with one-of-a-kind creatures of their own, drawing them, and very quickly understanding the rules. My middle daughter came up with a “rain deer,” this little deer that has a storm cloud following it.

RS: I love it.

JA: There’s no end of that kind of play. I love it, too, and I might steal it and put it in my book.

RS: That’s what kids are for, right?

JA: Just harvest them for material. In some ways it’s liberating that I’m not dealing with canonical fantasy creatures, because it means any kind of creature you could think of could possibly belong in this world. That’s how it feels for me in my writing, and hopefully that’s how it will feel to kids when they read it.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!