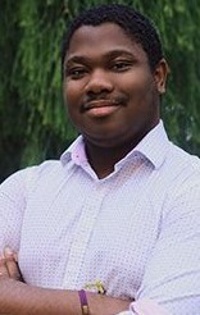

Kosoko Jackson Talks with Roger

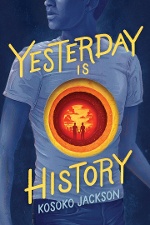

As I told my husband while I was reading Yesterday Is History, “Well, it’s a time-travel novel with a gay love triangle, and it’s set down the street from our house.”

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

As I told my husband while I was reading Yesterday Is History, “Well, it’s a time-travel novel with a gay love triangle, and it’s set down the street from our house.”

Roger Sutton: It’s tricky to write about time travel, don’t you think?

Kosoko Jackson: Oh, very tricky. I was told the two things you don’t put in a book are time travel and a love triangle.

Kosoko Jackson: Oh, very tricky. I was told the two things you don’t put in a book are time travel and a love triangle.

RS: And your book has both! Why shouldn’t you put those things in?

KJ: The rules of time travel are incredibly important to stick to — you have to establish rules in the beginning. Then you can find ways to break them, but not in a way that feels too contrived. All the ripple effects — if your characters see themselves in the past, you create a paradox. The butterfly effect. There are so many different ways that time travel can get out of hand. It’s a very messy thing to write. As for love triangles, we just have so many of them! Especially for my generation of millennial writers — The Hunger Games, Twilight — there’s a huge oversaturation. A lot of love triangles don’t feel like actual love triangles. They’re just stops along the way to the one true love, with the other person just there to cause conflict. You can tell who the main character is going to end up with. Love triangles have exhausted our readership, and writers shy away from that. But I like to give myself challenges, so I thought, “Why not include both?”

RS: How did you pick the time period that Andre was going to travel back to?

KJ: I have older parents, in their seventies and eighties. My mother lost a lot of people during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. During the civil rights movement, my grandmother’s house had been a place where teens and college students were educated. I’ve always grown up around history, and I wanted to pick a time period that’s kind of a mixture of things that represent my family. A time when the civil rights movement was still in the present, and the gay rights movement, too. The 1960s and ’70s was such a pivotal time in our country, and it embodies, through that setting, all the different identities that Andre is, even if it’s not all reflected on the page.

RS: Did you grow up in Boston?

KJ: I did not. I did an internship in Boston during college for four months at Northeastern. I fell in love with Boston and was going to move there, but ended up in New York instead.

RS: As I was reading, I kept seeing Boston back then. I think I’m probably four years younger than your Michael.

KJ: Oh, that's perfect.

RS: It’s roughly the same era. I grew up here. That was a strange experience for me.

KJ: Did I accurately portray it?

RS: Yeah, I think so. What was even stranger for me, though — when I think of the first gay YA books published in the late ’60s and ’70s, it was such a completely different world. When I say “soapy” here, I mean it in a good way — that your book is like a romance novel. The thought of a romance novel with a gay love triangle shows me how far we’ve come.

KJ: That’s a good way of looking at it. I remember when I started seeing books, to the point where I was just absorbing them — when we still had Borders. There was a book series called Rainbow Trilogy [Rainbow Boys, Rainbow High, and Rainbow Road].

RS: Alex Sanchez.

KJ: Right. I snuck it after school. I would go to Borders with my mom, for a half hour, forty-five minutes, before we went home. I’d sneak into the corner and read it. It felt like such a risqué thing to do! Now we have so many LGBT books — there are so many that I can’t even read them all. Between middle-grade, graphic novels, YA — we’ve come so far. We still have a long way to go, but we’ve come so far, and it’s really cool to add to that history.

RS: You say on your website that you write queer Black stories for queer Black teens. Is that who you think of as your audience?

KJ: Yes. I like to think that I write for myself, which a lot of YA authors say. When I was a teen, I didn’t see many LGBT books, especially many LGBT books with gay Black characters — even in TV and film — who weren’t some kind of stereotype. They were the Black kid who was hiding his sexuality, or he’s assaulted in jail and that’s why he’s gay. I want to write characters who are middle-class or lower-upper-class, who are gay, and who are thriving. I want to push back against the identity drama that a lot of Black and queer protagonists play into, which our white and straight counterparts often don’t have to address. They’re able to go on adventures that focus on love, or on speculative ability, in ways that queer Black characters are oftentimes not allowed to do, at least in those types of books I saw growing up. I always try to write characters that push against that. Books that have coming-out stories are incredibly important, but there’s room out there for more stories than just those.

RS: Right. Don’t hit me, but it just came to my mind that time-traveling Andre is a Magical Negro.

KJ: I had that same joke when I was writing it. My mom read it and was like, “The book is about a Magical Negro?” And she went on, like, a five-minute tirade about it.

RS: What do you see as the relationship between your own reading as a teenager and your writing for them now as an adult?

RS: What do you see as the relationship between your own reading as a teenager and your writing for them now as an adult?

KJ: That’s an interesting question. When I was a teen, I read a lot of middle-grade and lower-YA fantasy books. Two of my favorite series were the Pendragon books by D. J. MacHale and Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus sequence. Those got me through middle school and early high school. Those stories where the main characters weren’t perfect — they had trauma, they had friends who were complex — those were the types I wanted to write. Books that straddle the line between commercial fiction and real-life issues that teens can relate to. Yesterday Is History is very much definitely a romance. It’s also about a type-A, college-bound kid, whose world comes crashing down in a way he cannot control, and how he can recover from that and put himself back together to find out who he is. As someone who struggled through the shift between high school and college, I have to say that we put a lot of pressure on teenagers to know exactly who they want to be and never make mistakes at seventeen, eighteen years old. I love to write stories that reflect that it’s okay to change your path or not know who you are yet. That’s very important to me.

RS: Do you see yourself in Andre?

KJ: I see part of myself in Andre. In high school I was a straight-A student. I got into a scholarship program that almost paid for my whole tuition. I was going to be a PhD and an MD. I had a whole professional successful life plan. But I screwed it up the first year, and my life kind of came crashing down. I had to go home because I flunked out of school. I took those feelings and applied them to Andre and the fact that he might be held back — how do you put yourself back together when everything you were working toward and your whole identity are broken?

RS: I don’t know how young people do it today. When I was graduating from high school, it was okay to go to college and figure out then what you wanted to do later. But now it seems the pressure starts much earlier.

KJ: I think every generation’s harder than the last. I remember having two to five extracurriculars that you were president of and a 3.7 GPA could get you into a top-tier school, even an Ivy. Now when I talk to high school kids, they have eight AP classes and ten extracurriculars. I don’t understand how kids are expected to succeed and develop healthily and also just be kids. How do you have fun and grow when so much of your time has to be spent reaching for that constantly goalpost-moving end goal, and no one really knows what they want to do.

RS: How do you think it is for gay kids in the high schools these days?

KJ: I think for a lot of gay kids, especially with TikTok or access to social media — in some ways it’s easier to find your community, not necessarily in your school or your neighborhood, because our world is so much more interconnected. But that also causes a lot more pressure. When I was a teenager, if you made a mistake or did something foolish, it wasn’t going to live online forever. You didn’t have to worry about some distant person posting your most vulnerable moment online and it spreading like wildfire to every corner of the world. But on the flip side, I was the only out kid in my high school, and that was really hard. Now if you’re a gay kid, you can go on social media apps and meet other gay kids. I don’t think it’s easier. I definitely don’t think it’s harder. I just think it’s different.

RS: How do you think you’d fare in high school today?

KJ: Are you saying with the knowledge that I have now, in high school?

RS: Yeah, imagine you’re time-traveling.

KJ: I think I would do well in high school. I work in digital communications, and my whole life is mostly online, so that part of me would probably be the same. I’ve always been a creative kid, and my creativity would probably be a lot more appreciated than it was at my very small school. I might have developed faster in some ways — positive and negative ways — if I was in this generation of kids. A lot of people say, “I was born in the wrong time period,” but I was born in the right time period. It’s really cool to be part of the generation that started to use social media, and to pass that torch on to the next generation. Millennials have lived through so much that has informed who we are, as a society. I’m pretty happy with who I am.

RS: Have you ever been in a love triangle?

KJ: I have never been in a romantic love triangle, besides first semester of college, when I thought I was in love with a guy, and he was in love with another guy. It was a very short-lived thing.

RS: Did you know from the beginning how things would end up for Andre, in terms of his love triangle?

KJ: I didn’t really know until I wrote the last chapter. My editor, Annie Berger, and I went through a lot of edits about how to get there. There were several points when I was like, “This moment could completely shift his relationship, who he’s going to end up with.” I feel like this is the right ending for the book, but there’s probably a universe out there where Andre ends up with the other guy.

RS: I remember Nancy Bond’s Another Shore, a YA time-travel novel from about thirty years ago, where this girl goes back in time to eighteenth-century Nova Scotia, and she can’t get back. And she has to learn to make her peace with just being stuck there.

KJ: I really like those types of stories. I feel like writing stories that are perfectly wrapped up — when you have such a fantastical premise — in some ways that seems a little bit like a cop-out. I like messy stories, where the choices are not the logical ones that a thirty- or forty-year-old adult would make, because teens don’t make logical choices. Especially with speculative ability, where anything is possible, anything can happen.

RS: What will happen with your next book?

KJ: My next book, which is coming out with Sourcebooks Fire in February or March of next year, is tentatively titled, though it’s going to change, All Kingdoms Must Fall. It’s a Black Lives Matter science fiction book, about an aspiring high school journalist who ventures to Baltimore after protests break out around police officers who murdered a Black man. Baltimore issues a military lockdown, which takes the form of a giant impenetrable dome that locks everyone inside.

RS: You do love your genre-busting, don’t you?

KJ: I struggled for a long time with being a writer who is comfortable with writing genre fiction and also things that aren’t the most typical within the genre. It’s so important to do that as someone who is a Black queer man in America. Centering stories with Black queer kids, to me, is already an act of resistance. But it’s important to add, inside the stories, the type of struggles that Black queer kids deal with, without feeling like, “Oh, this is a character that could have been a white kid.” Does every story have to have that? Absolutely not. But it’s important to have those stories where we can intersect. Science fiction can talk about difficult topics. We see it in adult science fiction — we talk about colonization, genocide. So why can’t we have that in YA?

RS: I'm with you.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!