Lighting the Candle: The Year I Turned Ten

The year I turned ten, my father moved us from my island of Puerto Rico to Buenos Aires, Argentina. For him, it was a long-awaited sabbatical. One he dreamt of spending in his patria. For me, it was a bittersweet experience. That year became the year I parted from my best friend, the year I was homeschooled — and the year I first saw myself as an artist.

"Una vez que un objeto ha sido incorporado a una pintura, acepta un nuevo destino."—Georges Braque

The year I turned ten, my father moved us from my island of Puerto Rico to Buenos Aires, Argentina. For him, it was a long-awaited sabbatical. One he dreamt of spending in his patria. For me, it was a bittersweet experience. That year became the year I parted from my best friend, the year I was homeschooled — and the year I first saw myself as an artist.

In the big city, tutors came in and out of our rented apartment every weekday. For all the hours I must have spent with them, I barely remember what I studied. In contrast, memories of that first time Mami took my sister and me to her childhood friend, the portrait artist, are seared in my brain.

Her name was Morena. Morena held private drawing lessons in her family apartment overlooking Plaza San Martín. She must have encouraged Mami to bring the two of us to try her class. I was both thrilled and nervous. I didn’t know what it would be like to be making art among strangers. (My thirteen-year-old sister didn’t count. She ignored me most of the time.)

We got out of the elevator on the tenth floor of the nineteenth-century building and rang the bell. Morena answered, embraced us, and gestured us in. The airy living room was decorated with English-style furniture that must have been handed down through many generations. Tall, wide windows anchored the north wall. And gazing through them, I could see beyond the park’s century-old banyan trees all the way to the port where Río de la Plata debouches into the Atlantic Ocean. Natural light poured in, casting soft shadows. I felt my chest tighten as I noticed that the other students were all grownups.

Morena pointed me toward the kitchen. On its table were colored pencils and paper. She asked me to draw from memory anything I wanted. Homesick, I drew what I most missed: palm trees, blue waves, sand, seashells. Morena nodded at my landscape and sent me over to join the group.

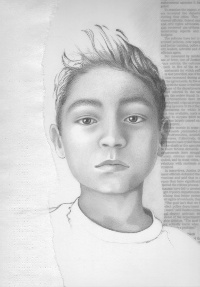

I sat in the one empty chair in front of the boy, our model. He must have been a little older than me. His skin was dark, his bangs thick and shiny, and his eyes mahogany like mine. Morena instructed me to draw his face with graphite pencil. She said to imagine a grid in front of what I saw. She said to measure distances from one point to the other. She said to look at how one shape related to others nearby. I listened. I heeded. And I began to discern. All surroundings vanished and I got lost in the act of transferring what my eye perceived onto the drawing paper. I followed the shapes. I relished each stroke of the pencil. The rhythm was soothing. I forgot I missed my island, my best friend, my school. I forgot that I didn’t get along with my sister, and that I had no friends in this foreign country. In the void of what I missed, I found a love I did not want to part from, ever.

I sat in the one empty chair in front of the boy, our model. He must have been a little older than me. His skin was dark, his bangs thick and shiny, and his eyes mahogany like mine. Morena instructed me to draw his face with graphite pencil. She said to imagine a grid in front of what I saw. She said to measure distances from one point to the other. She said to look at how one shape related to others nearby. I listened. I heeded. And I began to discern. All surroundings vanished and I got lost in the act of transferring what my eye perceived onto the drawing paper. I followed the shapes. I relished each stroke of the pencil. The rhythm was soothing. I forgot I missed my island, my best friend, my school. I forgot that I didn’t get along with my sister, and that I had no friends in this foreign country. In the void of what I missed, I found a love I did not want to part from, ever.

That morning in Morena’s apartment, three hours dissolved into three minutes. Too soon, Mami arrived to pick us up. She joined Morena in peering over my shoulder. And when I turned to look at them, I saw pride.

In the end it’s like Braque says: “Once an object has been added to a painting, it accepts a new destiny.” Being thrust into the midst of a group drawing from the model revealed to me what I would become. It happened during my father’s sabbatical in Buenos Aires. That morning I learned that, for me, creating is like breathing.

From the May/June 2021 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Pura Belpré Award at 25. Find more in the "Lighting the Candle" series here. Graphite portrait from Lulu Delacre's book Us, in Progress, using Morena's teachings. Us, in Progress (c) 2017 by Lulu Delacre.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!