Lighting the Candle: Unearthing a Writer

When word spread that homeroom assignments had gone out, every sixth grader at Roosevelt School waited by their mailbox, promising God they’d be good the rest of the year if Mrs. Arnoldus’s name was on the teacher assignment postcard. Lucille Arnoldus hadn’t started out as a middle-school teacher. She’d been an archaeologist and anthropologist; then transformed into a small-town Indiana Jones with wild hair and thick glasses who dared to teach school wearing jeans. Gasp!

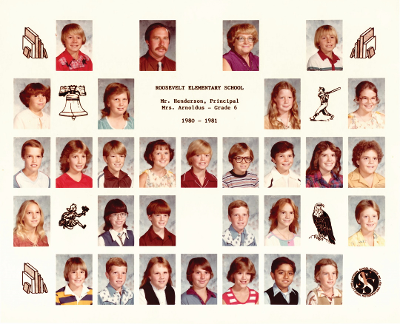

Mrs. Arnoldus (top row, third from left) and Donna Barba Higuera (second row from top, far left). Photo courtesy of Donna Barba Higuera.

When word spread that homeroom assignments had gone out, every sixth grader at Roosevelt School waited by their mailbox, promising God they’d be good the rest of the year if Mrs. Arnoldus’s name was on the teacher assignment postcard. Lucille Arnoldus hadn’t started out as a middle-school teacher. She’d been an archaeologist and anthropologist; then transformed into a small-town Indiana Jones with wild hair and thick glasses who dared to teach school wearing jeans. Gasp! When my postcard arrived, Mrs. Arnoldus’s name was on it!

On the first day, she shared how she’d spent her weekends digging at a Yokuts Village site near my home in central California. The captivating tales I’d heard about this teacher were all true.

A few months into the year, she split our class into two and presented an assignment for each group to create an ancient civilization with its own language and history. We would bury our work in a box for the other group to find, then they’d excavate our society and read about what had happened to us. (Surely it must have been something pretty horrific if they’d found us three thousand years later buried in the four-by-six-by-two-foot sandbox of a central Californian middle-school playground!) I begged for the job of letter writer in our group. What better civilization for me, a true product of the seventies, to mimic than the Sleestak from Land of the Lost? But I could do better than the hissing, zombie-esque horrors that terrorized Holly, Will, and Chaka. My brain came alive with ways to make my more sophisticated lizard-humanoid culture the stuff of legends.

My group began creating our civilization’s artifacts: a monetary system, an alphabet, and finally my letter. I spent each day after school writing that letter with the detailed story of our civilization and its ultimate demise. When I’d finished creating my story to Melvillian proportions, I translated it into the cuneiform-type symbol alphabet we’d also created. I proudly buried my story along with our carved modeling clay Rosetta Stone tablet and the artifacts hinting at who our culture had been eons ago.

In the desert heat, our class sweated and dug and had the best time of our lives. Then, the other team found my letter…

Its grand discovery and subsequent translation did not go over as I’d expected. The other team scowled at its monumental word count. How could they not appreciate the profound story I’d written?

Mrs. Arnoldus, sensing my humiliation, pulled me aside. She spoke these encouraging words: “You created an amazing, imaginative world, Donna. Now go write other worlds and stories.”

I went from hot tears pouring down my dirty face to a soaring feeling in my gut that I’d found life’s purpose. It suddenly didn’t matter what anyone else said or thought. Those few words coming from this magical woman were all I needed. I did continue to write short stories using the strange ideas that came to mind, or retellings of folklore and mythology I’d heard. Now, novels.

Years later, I learned that Mrs. Arnoldus had died. I found her obituary and read about how she’d been a teacher, anthropologist, and professor at a local college. There was no service. No fanfare.

No one had written about her classroom archaeological/anthropological digs. They didn’t mention her example to young girls of breaking social norms. No one wrote of how she’d told a sweaty, dirty-faced kid that her made-up history of a lizard-humanoid civilization was imaginative, and how on that day she had helped create a writer.

How had they left out the most important part of who she was?

So, I’d like to make an addition to her obituary:

Lucille Arnoldus was an inspiration to children, who never judged and who, like the archaeologist she was, sniffed out her students’ truths and encouraged them to seek out their passions.

By the way, Mrs. Arnoldus also mentioned I had potential as an archaeologist. I might try that next.

From the May/June 2021 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Pura Belpré Award at 25. Find more in the "Lighting the Candle" series here.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!