Lynne Rae Perkins Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by![]()

For the education-minded among you, let me just say about Frank and Lucky Get Schooled that I don't think I've seen more Core Standards introduced in a single book. And I'll bet you didn't know they could be this much fun, either. Newbery Medalist Lynne Rae Perkins and I talk about pictures, books, and the making of them both.

For the education-minded among you, let me just say about Frank and Lucky Get Schooled that I don't think I've seen more Core Standards introduced in a single book. And I'll bet you didn't know they could be this much fun, either. Newbery Medalist Lynne Rae Perkins and I talk about pictures, books, and the making of them both.Roger Sutton: I would like to know where this book began, because it's a book about everything. What was your starting point?

LRP: A long time ago, I had an idea to make a book for preschoolers who had older siblings who were going to school. It would look like a notebook with dividers, and there'd be different subjects and things they could do, so that they could feel like they were going to school also. I didn't get very far, but it was an idea that was in the back of my mind. And then we had a dog, Lucky, who was fourteen years old. For the last year of his life, I would take him on these walks that were long but didn't cover much distance. He would walk about twenty steps and then lie down in the middle of the street, and I would sit down with him, and then we would go on. While I was taking these walks I thought a lot about the dog that he had been when he was younger. He was really active. He could run for miles. On one of our walks — I think my son Frank must have been home from college — the title for this book just popped into my head. Frank and Lucky Get Schooled. I wrote it down, didn't do anything with it right away. When I went back to it, I thought of following Frank and Lucky from when they were young to when Lucky was an older dog.

RS: A very different book.

LRP: That went by the wayside. With most of my books, there are some parts that pop up right away, and other parts I have to wait for.

RS: Your picture books, to me, always seem to have an intense braid between the text and the pictures. It's hard for me to say this part must've come first. Are you working on them in concert all the time?

LRP: Often they do go back and forth the whole way, and I don't know until the very end what the last line of the book is going to be. That was true here — the very last line of the book was the last thing that happened. In this case I actually did have a whole manuscript before I started drawing. What's most fun for me are when things surprise me and also when ideas pop into my head. Ideas mostly come from the work itself. Often when I'm drawing, the words will be bouncing around in my head, and when I'm writing, ideas about the drawing happen. I love that. I don't like things to be static when I'm working. It starts to feel a little boring. So I like going back and forth.

RS: It sounds like you don't enjoy a lot of structure.

LRP: In some ways I'm very structured. I'm structured with time. But I do like to be surprised.

RS: I never knew where this book was going to go next. Where it does go never feels forced or illogical, but you allow each moment to go to the next, and the reader is surprised along with Frank and Lucky — and, apparently, you.

LRP: It's true. I started thinking about that when I was working on As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth.

RS: Which is a novel.

LRP: Yes. I had read that Dickens's novels were often published serially. I thought it would be fun to write a book, just sitting down and writing a chapter every day, not knowing what would happen next. So that's how I wrote the first draft. And then of course I had to go back and make sure everything worked and change things. One of my favorite moments in that book was when something happened that I had no idea was going to happen. I don't want to make myself sound that spontaneous, because I'm not. I generally have an idea where I want to go, but I don't know how I’m going to get there.

RS: I find that even in book reviewing. I'll read something that's been assigned to me for review, and I'll think I have a pretty good idea of what I think and what I need to say, but then when I write the review I discover new things I think about that book.

LRP: I love that when you're writing your mind is sort of figuring things out on its own, without you directing it.

RS: Right. And then, as you say, you've got to go back and whip everything into shape. And not every seemingly brilliant spontaneous idea is in fact as good as it first seems.

LRP: Right.

RS: But it is wonderful the way they topple out. Is it the same thing with drawing?

LRP: Yes. Not too long ago I made a drawing for a book I'm working on now. It's a little drawing of a girl who's ashamed and upset and hides in the corner of the closet. It's the kind of drawing that I feel like I'm really good at. If I could make a career out of drawing little girls hiding in corners, I would do really well. But I know if I did that all the time I would get tired of it. I love when I'm trying to do something I don't know how to do, and it kind of figures itself out along the way. And that means messing up a lot. That means throwing away a lot of drawings. But I do love that discovery of when you're trying to figure out how to make something work, and it happens in a way that you didn't predict.

RS: That seems so frustrating to me as a word person. You can work for hours on a drawing, which is not one word after another, the way I work, and then have to chuck the whole thing out. You can't just edit.

LRP: It's really daunting when you have just spent a lot of time on something to think about tossing it out. But once you've started something better that's working right, then it's pretty easy to let the first one go.

RS: I see what you mean. Now, Frank and Lucky learn a lot in this book. What did you have to learn — about science and math and all the things that the two of them explore — in order to tell their story? Or was this all stuff you already knew? In which case you're better educated than I am.

RS: I see what you mean. Now, Frank and Lucky learn a lot in this book. What did you have to learn — about science and math and all the things that the two of them explore — in order to tell their story? Or was this all stuff you already knew? In which case you're better educated than I am.LRP: Some of it just involved thinking about, for example, the different kinds of science, what chemistry is. Science about what everything is made of, the kind of thing that can change into another kind of thing. That was more or less reading how chemistry was described in different books, and then trying to synthesize it into something simple that made sense. So there was that kind of learning. And then there were things like the history piece, where I looked up famous dogs in history. I knew what fractions were. I knew what infinity was. Being a previous art student, I knew about some art concepts.

RS: How did you decide what Frank and Lucky were going to learn?

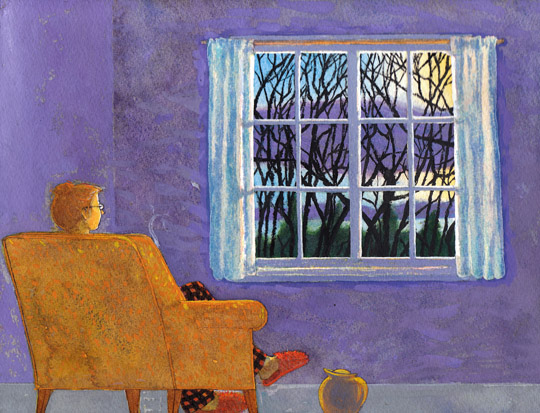

LRP: I had a general outline of subjects. The way I start my days is my husband brings me a thermos of coffee up to the bedroom.

RS: That's a sweet deal.

LRP: I creep over to my chair and sit there with my notebook and my thermos of coffee. It's my best time for thinking, because I haven't started thinking about anything else yet, and the thoughts can kind of go in and out of my head.

RS: Do you have to make yourself do this?

LRP: No, I like doing it. It's one of my favorite times of day. I'll have an array of notes, things that I want to think about. Something will start to take shape, and I'll play around with it. It's not usually an intense time. It's sort of a playful time. But it's when some really good thoughts arise.

RS: When you're still almost half-dreaming.

LRP: Yeah. After I do that for about an hour, I get dressed and go down in my studio, and that's a different kind of working.

RS: How related is the time up in your bedroom to the time down in your studio? Or are they completely separate?

LRP: They're really related. In the bedroom time I have generated thoughts, and then in the studio I take those thoughts and try to shape them into something. The morning time is also a time when I look at what I did yesterday. That's often a jumping-off point for today.

RS: Pretty structured.

LRP: Yeah. I'm German, after all.

RS: I take back my earlier remark about spontaneity.

How did you decide to distribute information among the main text, the dialogue within the pictures, the speech-balloon dialogue, and the illustration itself? Because they're all completely interdependent, which I love.

LRP: That feels like a really natural thing to me, not something that involves a lot of decision-making. It seems like it just evolved in a really easy way.

RS: Does that seem generally true to you? Because you are a person who doesn't seem to have firm boundaries about what's going to be text, what's going to be picture, what's going to be in-between.

LRP: I've done that in a number of books. I'm heavily influenced by Edward Ardizzone, how he has people talking in little speech bubbles. I love those. And also Edward Gorey. Those are two of my favorite people. I don't feel like it's something I invented myself, rather something I absorbed and continue to do.

RS: It seems like we're in a time now where the picture book is a lot freer. You said you began this idea as a picture book for preschoolers, but, really, it's not a preschool book anymore. Picture books go all the way up, through teenagers. Middle-grade novels are now more heavily illustrated than they were even ten years ago. There seems to be a lot of fluidity, which speaks to the way you work.

LRP: That's really interesting. I remember when I was working on All Alone in the Universe, and Robin Roy was my editor. When I first sent it to her, she said kids this age don't want pictures in their books. By the time I finished the book, she was saying, "More pictures!" It really does feel, partly because of graphic novels kids read, like there's a lot of freedom with how you can use both images and words, because we think in both of those ways.

RS: You think of a word, you see the picture. You see a picture, you think of the word. I do, anyway.

LRP: Right. I think we're also so conditioned by watching movies. There will be scenes in a movie where people are walking through the park, or through a forest, and you're seeing the flickering leaves around them, and they're walking, but you're also hearing their words. It's an interaction between where they are and what they're saying that's both visual and verbal.

RS: And you just take that all in at once.

LRP: Yes.

RS: It's like thinking about breathing. Once you start to think about it, it becomes difficult to do.

LRP: Yes, it does.

RS: Are you surprised at how your career has turned out, as both a novelist and a picture-book creator? It's pretty rare.

LRP: I don't think about it that much, but sometimes I am surprised by that. I sometimes wonder why I didn't turn out to be the kind of picture-book writer who has stuffed animals that go with their books. That would be okay with me. I think, "How come? How come that didn't happen?" But I like that I get to do both things.

RS: In order to get the stuffed animals, you've got to make a series about the same character.

LRP: Right.

RS: Have you ever done more than one book about the same set of characters?

LRP: Only the characters who are both in All Alone in the Universe and Criss Cross. But there's no stuffed Debbie doll.

RS: I'll see what I can do about that.

More on Lynne Rae Perkins from The Horn Book

- Horn Book Magazine starred review of Frank and Lucky Get Schooled

- Calling Caldecott: Frank and Lucky Get Schooled

- Five Questions for Lynne Rae Perkins

- Virginia Duncan's profile of 2006 Newbery Medal winner Lynne Rae Perkins

Sponsored by![]()

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!