Marieke Nijkamp Talks with Roger

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

SOURCEBOOKS

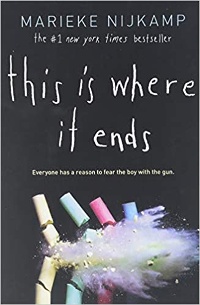

Marieke Nijkamp's first novel, This Is Where It Ends, is unfortunately timely, telling, through multiple points of view, of a young shooter who holds an entire school hostage for one harrowing hour. Blood is spilled, secrets are revealed, truths are told. Marieke (pronounce it like the Jacques Brel song of the same name) spoke to me from her home in the Netherlands.

Roger Sutton: You are Dutch. How did it happen that this book is written in English and being published here

Marieke Nijkamp: It actually came to pass quite by accident. I'd been writing in Dutch for quite a few years before I made the switch to English. A few non-Dutch-speaking friends of mine would have me translate things I was working on into English so they could get a sense of what I was doing every time I sat curled up in a corner somewhere with a notebook or my laptop. I'd been writing young adult stories without realizing it, because it wasn't quite a market here, at that point, the way it was in the U.S. Mostly on account of traveling, I'd been used to speaking English, so using it as a way to tell my stories felt very natural. That was basically how that experiment started.

Marieke Nijkamp: It actually came to pass quite by accident. I'd been writing in Dutch for quite a few years before I made the switch to English. A few non-Dutch-speaking friends of mine would have me translate things I was working on into English so they could get a sense of what I was doing every time I sat curled up in a corner somewhere with a notebook or my laptop. I'd been writing young adult stories without realizing it, because it wasn't quite a market here, at that point, the way it was in the U.S. Mostly on account of traveling, I'd been used to speaking English, so using it as a way to tell my stories felt very natural. That was basically how that experiment started.

RS: Do you feel like a different person writing in English? Do you think you write different things?

MN: I actually do. I think it has to do with the way we use language in general. The rhythm of language, the melody, and also the cultural components really do influence the way we tell stories; the way I tell stories, certainly. I tried to translate an English story of mine into Dutch at one point, and halfway through the second sentence it changed into something completely different. That's something to say about translating—it's an art and craft that I do not possess.

RS: What was it like for you, then, coming from the outside, but writing in English, about what is a very American problem, at least these days?

MN: At first it felt incredibly intimidating, and I felt completely unequipped to talk about it. But I started working on the book because I was feeling just confused and baffled by how often these situations happen and how horrendous they are. I wanted to explore that and find a way to better understand. As a writer I do that by telling stories, and by trying to get as close to a situation as I can, even fictionally.

RS: Which part of the story occurred to you first?

MN: It started out as a conversation with a friend about gun safety and school violence. It left me with so many questions, and it began this story in the back of my mind, these characters who wanted me to tell their story. That's something I hadn't really quite experienced before. I'm usually the type of person who very carefully plots stories and knows exactly where to go from one moment to the next. But these characters occurred to me, and refused to let me finish another story I was working on, because I was so enthralled by what they had to say.

MN: It started out as a conversation with a friend about gun safety and school violence. It left me with so many questions, and it began this story in the back of my mind, these characters who wanted me to tell their story. That's something I hadn't really quite experienced before. I'm usually the type of person who very carefully plots stories and knows exactly where to go from one moment to the next. But these characters occurred to me, and refused to let me finish another story I was working on, because I was so enthralled by what they had to say.

RS: I think it's a very dangerous story, and I mean that in a good way. The storytelling is dangerous. And you let us know pretty early on in this book that it's not going to be safe. That no one, essentially, in the book is safe from the shooter. We don't know until the very end of the story who's going to make it out alive.

MN: That was a very conscious choice for me, and also something that quite terrified me, writing it. I wanted to get as close as I could to the experience of being in that kind of situation, while still staying on the side of fiction, of course.

RS: One hopes.

MN: I feel like it's important to have these types of discussions in fiction, too, even the ones that are dangerous in a sense. We only talk about tragedies after they occur. After something absolutely terrible happens we try to find ways to put it into words. We rarely ever talk about it beforehand. We rarely create safe spaces where we can discuss things that are so quintessential to teens' lives these days. Books can play a very important role in that.

RS: Do you think a book like yours can help prevent these things from happening?

MN: You're giving me the hard questions.

RS: I'm not asking you to say, yes, my book will save lives. But books in general. How do they help?

MN: Books in general, especially books that reference teens' experiences and make them feel seen or heard, can create a sense that you're not alone even when it may seem like it. In that regard, books play a very important role in many teens' lives, in making them feel like they matter. Sometimes, especially for teens in difficult situations, it can seem like the entire world is against them. Just having that sense that there's someone else out there who has gone through what you've gone through, or who can just empathize, is so incredibly important.

RS: How do you balance the need for telling a good story with getting your message across?

MN: The story always comes first. I don't write with a certain kind of message that I have to tell. I certainly don't want my books to be didactic, telling teens how to live their lives. But I do think it boils down to empathy. If you tell a good story it means getting close to teenagers' lives, getting close to the things that motivate them, things that matter to them. If you do that, and if you approach that respectfully, you can get to a place where you have a common understanding of each other. That helps in getting the conversation going. Being a conversation-starter is one of the most important, or even just the best, things a book can do. There's nothing like picking up a book and going over to someone else and talking about the things you experienced or the things you felt, and how that changes you, or how that makes you feel. That is more important than any message, in the end.

RS: It's interesting. The last interview I did for this series was with British publisher David Fickling, and he said that when he reads a book he really loves, he doesn't want to tell anybody anything about it. The only thing he wants to do is say, read this.

MN: That is so interesting. I tend to be that person who picks up a book and carries it under their arm and walks around pushing it into people's faces.

RS: How did you decide to make the entire action of the book fall within a single hour? It's pretty intense.

MN: To be honest, I asked myself that question many times while writing. I mostly wanted to convey that when a tragedy strikes, disaster strikes, it almost does feel like time slows down or stops entirely. Even a minute can feel like an hour or a day or longer. I wanted to use that as a way of exploring just how much has changed in such a short period of time. I gave myself those boundaries and stuck as close as possible to the situation itself, which obviously meant a little poetic license, because looking at average shootings, they don't last for 54 minutes. So I did make some allowances there. But I hoped to get the point across that everything that you thought you knew, even five minutes ago, can change utterly and completely, and what does that do to you as a person?

RS: I think it's a really effective literary device in this case too. When I started the book, I wasn't really paying attention to the timestamps beginning each chapter. But as soon as I realized how minute-by-minute the story was, it pulled me in even further.

MN: That's good to hear.

RS: You're on the board of We Need Diverse Books here in the States.

MN: True.

RS: We Need Diverse Books is all about increasing representation in books and in publishing and among writers, etc. Do you feel like an outsider, coming to this American story?

MN: I don't necessarily. I had been talking and writing about representation well before We Need Diverse Books happened. I grew up disabled, and there were many, many days and weeks and months I spent in hospitals, lying in bed, being able to do nothing but read books and watch television, and in my case that usually meant just reading books. With a very few exceptions—and those usually ended up being books like The Secret Garden, where even the disabled character is healed by the end, so it didn't really feel like a book for me anyway—I just never saw myself inside the pages of a book. That's something that caused me to start writing.

So that feeling, that necessity that stories should belong to all of us, motivated me from very early on. And it culminated in being a board member of We Need Diverse Books. I have to be conscious about the fact—and I do try to be—that I live in a different society, with different rules and different experiences of various kinds of marginalization. But that underlying need of readers to have both mirrors and windows is something I feel is universal, and is something I can speak to in that particular context.

RS: Sometimes I worry that our definition of what a mirror is has become too narrow. When I think of my own reading as a kid, I didn't just need little nerdy gay white boys to read about, even though that's what I was. I found my mirrors in lots of different kinds of characters. They could be animal characters, they could be female characters, they could be adults, they could be historical figures. Sometimes I feel like we're getting too literal about what we mean by a mirror.

MN: I think we can find mirrors in many kinds of books. I don't think that finding a mirror in a book or in a character that is supposedly unlike yourself means that everyone will always find themselves reflected in that way. Just looking at the books I read and my experience, there were certainly books that I identified with a lot, but there were also things I struggled with as a disabled kid that I would have loved to have seen in books and never saw. Just the ways life can differ if you have a disability.

Just having that sense of recognition would have been very important to me. I think that even when we do see ourselves in different kinds of stories, that doesn't negate the fact that there are many other stories we rarely tell, if ever. There is a need for those as well. The fact that we seem to have a narrow definition of mirror at times doesn't mean that those are the only stories we have to tell, but it means that those are the stories we aren't telling enough, and maybe we should try to be more inclusive.

RS: I understand that. Let's make sure that those mirrors are there.

MN: Yeah, absolutely.

SPONSORED BY:

SOURCEBOOKS

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!