Marla Frazee Talks with Roger

Ars longa, something Marla Frazee saw for herself during the quarter-century between conceiving of In Every Life and, uh, delivering it. We talk about time, creativity, and babies below.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Ars longa, something Marla Frazee saw for herself during the quarter-century between conceiving of In Every Life and, uh, delivering it. We talk about time, creativity, and babies below.

Roger Sutton: According to your author's note, you had the idea for In Every Life from a prayer you heard at church more than twenty-five years ago. What took you so long to figure it out?

Marla Frazee: That’s true. It’s based on a Jewish blessing, but I first heard it in 1998 in an Episcopalian church. From the minute I heard it, I thought, that’s a picture book. There were a lot of reasons it took so long. First of all, personally, I wasn’t ready. I saw it as a picture book, but I couldn’t unlock it. It’s like a house: if you can’t find the entrance, you can’t get in the door.

Marla Frazee: That’s true. It’s based on a Jewish blessing, but I first heard it in 1998 in an Episcopalian church. From the minute I heard it, I thought, that’s a picture book. There were a lot of reasons it took so long. First of all, personally, I wasn’t ready. I saw it as a picture book, but I couldn’t unlock it. It’s like a house: if you can’t find the entrance, you can’t get in the door.

Photo credit: Marla Frazee.

RS: What gave you the key, then, to continue your metaphor?

MF: I think it was living through the pandemic. So many things were taken away from us, and we were trying to figure out what was most important in our lives. Over the years I’d had all kinds of ideas about what this book should be, but I never could manifest any of them. I’d been changing the words, eliminating this phrase and adding another one. A ton of text revision.

RS: But you kept up with it over the decades.

MF: I did. Another point, though, is that the vision of the book was not always in sync with what was happening in publishing at the time. In the early years, it went from house to house, then was put in a drawer and taken out again later. I heard that my work was too light and funny to illustrate a serious text like this. Or the book is too serious; it’s really an adult book, not a children’s book. Or it’s too religious. I made changes to address the feedback, but then the text didn’t seem to quite have the same truths as when I’d first heard it. When I brought the manuscript out from a drawer again in 2020, I thought, this might be the right time. If there ever was a time for this book, I think it’s now.

RS: Had you been working with Allyn [Johnston; vp and publisher of Beach Lane Books] on it all along?

MF: It always circled back to Allyn; I have notes from her from over the years. She’d revisit it and ask important questions like “Why would this book be read again and again? Under what circumstances?”

RS: Do you have to have a completed text before you can start on the pictures?

MF: I don’t typically. Often, I start with pictures. In this case, I couldn’t get to the pictures until I finally figured out the key to unlock the house. I’d always seen this book’s pagination following a pattern: “In every birth” — page-turn — “blessed is the wonder” — page-turn. Sometime after I’d finally nailed down the text to the seven lines that they are now, I was on a long walk and thought, maybe that whole phrase [“In every birth, blessed is the wonder”] should be on one page, and then the spread after the page-turn should be wordless. It seems like that shouldn’t have taken me twenty-five years to figure out, but it did!

RS: That’s interesting, not even to think of it as a possibility.

MF: Right, it never occurred to me. But once it did, I thought, oh my god, I know how to do it. It just made the whole thing so much calmer. The part that was always difficult was how to sustain whatever the picture story was going to be, which I never really got to, over that page-turn. What is the visual connection? Putting the whole line on one spread meant that it could be taken in slowly, without feeling the need to turn the page to finish the sentence. Then the image after the page-turn with no words accompanying it offers a quieter, more expansive opportunity to continue the mood. It just made sense.

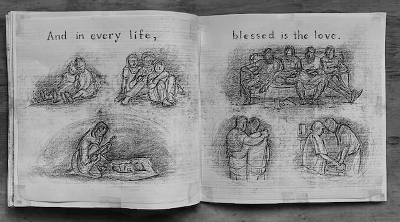

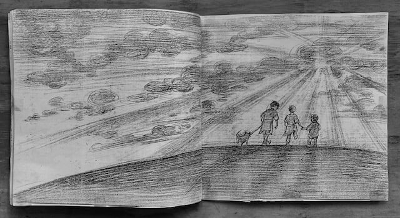

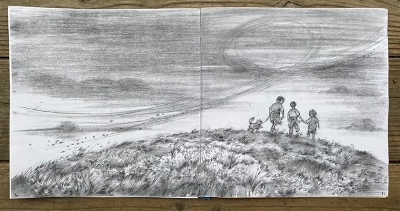

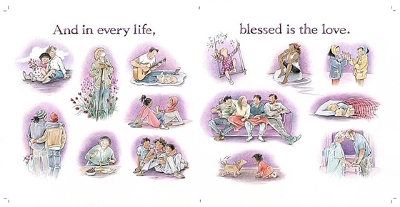

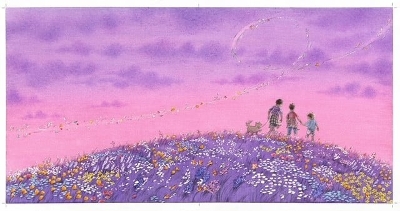

RS: Was that at the same time that you decided you were going to use the rhythm of vignettes plus a full-page spread?

MF: Yeah, that was it. I could show many ways the phrases, like “in every birth, blessed is the wonder,” can be true in the vignettes. And then when I turned the page, I could expand it out to the feelings we receive from larger experiences in our lives. For me, that is usually being in nature. It’s been very important for me to get out into the natural world and find resonance in wherever I am, whatever the weather is, with how I feel. It’s such an important aspect of life to me, and I need that on a regular basis. The wordless spreads enlarged each of those phrases to encompass the world itself.

RS: I want to climb that hill after “In every hope, blessed is the doing.” Is that a real hill?

MF: I spend a lot of time in the San Gabriel mountains right up against Pasadena where I live.

RS: I went to school in Claremont, so I used to walk there.

MF: Oh, that’s right. You’re familiar with those foothills. I’m on those trails a lot. It’s not a particular hill — it’s sort of a made-up version. But I wanted it to be in the golden light of these hills. Each of the seven lines has a certain palette and color scheme, which carries through the vignettes to the mood of that wordless spread.

RS: You start out with bright sunlight, and as you go, the palette gets darker and more saturated.

MF: Yes. I wanted to get more complex and deeper in terms of color. I feel like that’s what happens in our lives as we live through our days, too.

RS: You do love your books about babies, don’t you?

MF: I really do. There are themes I keep circling back to. I had done The Farmer and the Clown, The Farmer and the Monkey, and then The Farmer and the Circus. Right after that, I illustrated Mac Barnett’s The Great Zapfino, which also had a circus theme, and I thought, what’s going on with the circus thing? My second book, That Kookoory!, takes place at a fair. These things do tend to come back around in my work, but babies have been a constant, definitely.

RS: Are you nervous at all about getting into some of the same trouble you had with Everywhere Babies, in terms of showing different kinds of families?

MF: I’m not nervous about it personally. I’m nervous for our kids. I’m very nervous about banning books and what that means.

RS: We saw quite a bit of that complaint with Everywhere Babies — to me, that book is the best example of really? This tiny picture of two men and a baby is what’s bothering you?

MF: It’s hard to understand. What’s interesting is how much adults read into pictures versus how children read them. Children don’t have a bias. They’re just looking at a picture for what it is. A child who has two moms or two dads might look at a certain picture in a book a certain way, because that’s their experience. The child who doesn’t have that experience might see maybe two aunts or a mom with a friend.

RS: That’s right. I think if children see a picture of a female couple with a baby, for example, kids who don’t have lesbian mothers don’t think, oh, lesbian mothers. They don’t judge it either way. That’s not how they look at pictures. Why do we grownups?

MF: It’s very hard to understand all the judgment and fear placed in picture books, of all places, rather than thinking about real children growing up without representation in what they’re reading. That’s what’s scary.

RS: One thing I really love about this book is that the vignettes allow kids all kinds of entry into the story. They can tell their own stories about what’s going on in each of those little pictures, and they’re going to have favorites among them. They’re going to have pictures they don’t connect with so much. But I would think every kid is going to find a way into the book through those little situations you present. Each could create a story in itself.

MF: Thank you. I hope so. That’s always my hope. I definitely want this book to appeal to all ages, of course, but always children, mainly.

RS: Then, as you've said, on the next spread you expand on the situation with a single large image; I feel like that keeps it fresher. And anyone, child or adult, can respond to a landscape.

MF: When we look out at an expanse and we’re small in it, we’re awestruck by the largeness of the world, the grandness of the sky, whatever it might be. The scale is so much a part of the emotion you’re feeling. I wanted the book to provide that, too, not just the close-up moments, but the moments in which we don’t feel like we’re the center of the universe. There’s this whole other world out there that we’re part of. It's important to me in my own life to get that sense on a regular basis.

RS: It’s those little moments that lead to the possibility of the big feeling in the big picture, literally, I guess. It must have been tough to challenge yourself with such an abstract text. I imagine that would have been something that stopped you for twenty-five years, because it is harder when you don’t have a story.

MF: When I look back at some of my notes I wonder, what was I thinking? They say things like: "It’s about the golden moments in our lives, these times when things are just magical or just important." I was trying to describe what this book would be. But I never, ever got to a place where I was figuring it out in pictures. I was stuck.

RS: Do you see it as a religious book?

RS: Do you see it as a religious book?

MF: I see it somewhat as a religious book, maybe more spiritual. There was a point where I took out “blessed” to make it less religious. For a lot of years, it was “In every birth, there is wonder,” for instance, and my title was A Child’s Meditation. When I looked at it again in 2020, I thought, I don’t think anybody’s going to say this is too serious anymore. I don’t think anybody’s going to say it’s too quiet, or it's too religious. I think now it’s just the time.

RS: It’s very un-directive. This is a book I see a parent sharing with a young child, and every time they do, it’s going to be a different experience. Depending upon what happened to the kid that day, different things are going to hit differently. Which is kind of what we hope for with picture books, right?

MF: I really would hope for that to be true. All the picture books my three sons and I loved when they were growing up are still on shelves in my living room. I refer to them often. And so do they, because the books are so accessible. This has been true from the time they were still living in the house — when they were in junior high, high school, and college. It continues to be so beautiful to me to see their ongoing connections to and evolving feelings about these books that were so much a part of their childhoods. Now my oldest son is a dad, and he’s reading the books he loved to his own son. Books, when they become part of our lives, are part of everything.

RS: And you got to dedicate this one to your first grandchild.

MF: I sure did. My son who had that son is a type designer. He did the display type on the cover and title page, which was such a great gift. It really makes the cover sing — it’s so beautiful. When I first saw it, I knew, yes, that’s what it should be.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!