Middle-Grade Graphic Novels Make Good

Graphic novels for middle graders have a unique position for some readers, situated between picture books and non-illustrated works and straddling subject matter suitable for their developmental position between young childhood and young adulthood.

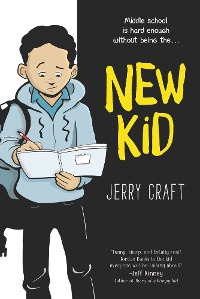

In 2012 the Horn Book published a special issue on the theme “Books Remixed: Reading in the Digital Age.” Of course graphic novels weren’t new at the time; but books such as The Arrival and The Invention of Hugo Cabret, with their copious illustrations and hard-to-classify format, were spurring us to pay a different type of attention to the middle-grade storytelling that we thought we knew. By the time Raina Telgemeier’s graphic memoir Smile, about complicated friendships and even more complicated orthodontia, won a Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor in 2010, it was clear that the graphic format was speaking directly to middle graders. Since then, graphic novels have taken off in the children’s publishing market — and their landscape, and currency, are vastly different today. In addition to indie and comics-focused houses and to established imprints such as Graphix at Scholastic (started in 2005) and First Second (2006, now part of Macmillan), other heavy-hitter publishers, including Random House, HarperCollins, and Abrams, have also recently launched or announced new graphic novel imprints. This year, momentously, saw the first-ever graphic novel Newbery Medalist, New Kid by Jerry Craft. Though there are some who still question graphic novels’ literary legitimacy, there’s no denying their place in the market.

In 2012 the Horn Book published a special issue on the theme “Books Remixed: Reading in the Digital Age.” Of course graphic novels weren’t new at the time; but books such as The Arrival and The Invention of Hugo Cabret, with their copious illustrations and hard-to-classify format, were spurring us to pay a different type of attention to the middle-grade storytelling that we thought we knew. By the time Raina Telgemeier’s graphic memoir Smile, about complicated friendships and even more complicated orthodontia, won a Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor in 2010, it was clear that the graphic format was speaking directly to middle graders. Since then, graphic novels have taken off in the children’s publishing market — and their landscape, and currency, are vastly different today. In addition to indie and comics-focused houses and to established imprints such as Graphix at Scholastic (started in 2005) and First Second (2006, now part of Macmillan), other heavy-hitter publishers, including Random House, HarperCollins, and Abrams, have also recently launched or announced new graphic novel imprints. This year, momentously, saw the first-ever graphic novel Newbery Medalist, New Kid by Jerry Craft. Though there are some who still question graphic novels’ literary legitimacy, there’s no denying their place in the market.

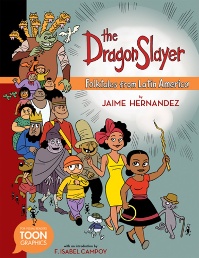

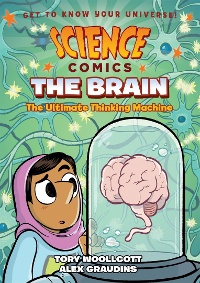

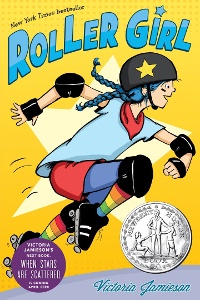

Today there’s something for everyone. Alongside superhero-themed tales and other visually sequential stories traditionally thought of as comics, we’ve got: anything new by Raina Telgemeier, Dav Pilkey, and Lincoln Peirce, their release dates practically celebrated as national holidays, à la Harry Potter, by fans (including my own two little ones). In addition to the 2020 Newbery winner, there are previous Newbery honorees (El Deafo, Roller Girl) and a Caldecott honoree (This One Summer, complete with profanity!). School stories (Secret Coders, Mr. Wolf’s Class, The Breakaways), camp stories (Be Prepared, Lumberjanes), family and friendship stories (Sunny Side Up, Stargazing, The Cardboard Kingdom). Sci-fi/fantasy (Amulet, Bone, Pashmina, 5 Worlds), reimagined fairy tales and folklore (Baba Yaga’s Assistant, Rapunzel’s Revenge, The Dragon Slayer). Retold history (tongue-in-cheek: Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales series; poignant and affecting: Drowned City, Child Soldier, Seeking Refuge). Historical fiction (White Bird, Bluffton). Science (Science Comics series). Revisioned classics (George O’Connor’s Olympians series). Graphic novelizations of modern children’s classics (A Wrinkle in Time, The Giver, The Crossover, The Baby-Sitters Club books). We’ve got Lowriders in Space, Cleopatra in Space, Zita the Spacegirl, Mirka in Space, CatStronauts. The variety in subject matter, genre, and illustration style makes it difficult to generalize about them — which can be a very good thing for keeping the format alive and vibrant.

Not everyone is a graphic novel fan, and that’s fine. They’re not usually my own first choice for leisure-time reading; as an avid novel reader, I sometimes find the brain shift (meld?) that’s required to process the interplay between words and pictures something of a challenge. But remember Elisa and Patrick Gall’s 2015 Horn Book article “Comics Are Picture Books: A (Graphic) Novel Idea” in which they state: “We believe that comic books and graphic novels (which we’ll refer to as ‘comics’ from here on out) are picture books, and that there are many types of picture books, from those for the earliest readers to those intended for young adults and beyond.” Seen in this light — if we take it as a given that graphic novels are picture books — it makes good sense that many middle graders may be attracted to them, having just graduated from picture books. Anyone who has read picture books aloud with or alongside young children knows how keen their powers of observation can be. Kids’ observations about graphic novels can have the same level of visual acuity.

Betty Carter reminds us, in her 2016 Horn Book article “Escaping Series Mania,” that picture books’ value goes far beyond reading comprehension — and that, unfortunately, children as young as first grade seem to be stopping reading them in favor of chapter books. Perhaps for some middle graders, graphic novels can offer a way to hold onto picture-book love a little longer.

Some graphic novels for this age range are intended to appeal to both their target audience and the grownups with different background knowledge who might also be reading and/or purchasing them. Dav Pilkey’s Dog Man books, for example, are hugely popular, entertaining, and silly spin-offs from his squarely kid-centric Captain Underpants series (itself likewise defined by meta structure and humor). The Dog Man books are definitely for kids: “‘Knock knock.’ ‘Who’s there?’ ‘A ladder.’ ‘A ladder who?’ ‘A ladder pooped on your head.’” But with titles such as A Tale of Two Kitties, For Whom the Ball Rolls, and Lord of the Fleas, and with jokes and call-outs to the classics, the Dog Man books demonstrate some adult awareness.

Victoria Jamieson’s 2016 Newbery honoree Roller Girl and Jerry Craft’s 2020 Newbery Medal winner New Kid, too, demonstrate awareness of grownups — their foibles and potential limitations regarding middle graders’ needs and emotions. In Roller Girl, protagonist Astrid’s hardworking librarian single mom is pretty rad — she lets Astrid do roller derby! Over the course of the story, Astrid’s friendships change dramatically and with lots of big emotions; it isn’t until a giant blowup that mother and daughter have an actual heart-to-heart. Mom: “You’ve had all of this bottled up inside of you for weeks? Sweetie, if you keep all your feelings inside like this, you’re going to explode.” Astrid: “So take it from me, kids: If you find yourself in hot water with your parents, try talking to them about your ‘crazy, mixed-up teenage feelings.’ It might just get you out of a jam.” New Kid is about an African American boy, Jordan, adjusting to life at private school as one of few children of color. He has positive interactions and makes close friends but also must contend with a librarian who hands a book called The Magic of the Magical Magicon to a white student and one called The Mean Streets of South Uptown to a Black student (both are tongue-in-cheekily deemed to be “real books…not those silly graphic comics”); and teachers who call one student of color by another’s name while others brush it off. Craft’s illustrations are very clear in their depiction of characters — there’s no way readers would mistake darker-skinned Drew for Jordan, for example — as the graphic novel format subtly and effectively reinforces the microaggression story line.

Victoria Jamieson’s 2016 Newbery honoree Roller Girl and Jerry Craft’s 2020 Newbery Medal winner New Kid, too, demonstrate awareness of grownups — their foibles and potential limitations regarding middle graders’ needs and emotions. In Roller Girl, protagonist Astrid’s hardworking librarian single mom is pretty rad — she lets Astrid do roller derby! Over the course of the story, Astrid’s friendships change dramatically and with lots of big emotions; it isn’t until a giant blowup that mother and daughter have an actual heart-to-heart. Mom: “You’ve had all of this bottled up inside of you for weeks? Sweetie, if you keep all your feelings inside like this, you’re going to explode.” Astrid: “So take it from me, kids: If you find yourself in hot water with your parents, try talking to them about your ‘crazy, mixed-up teenage feelings.’ It might just get you out of a jam.” New Kid is about an African American boy, Jordan, adjusting to life at private school as one of few children of color. He has positive interactions and makes close friends but also must contend with a librarian who hands a book called The Magic of the Magical Magicon to a white student and one called The Mean Streets of South Uptown to a Black student (both are tongue-in-cheekily deemed to be “real books…not those silly graphic comics”); and teachers who call one student of color by another’s name while others brush it off. Craft’s illustrations are very clear in their depiction of characters — there’s no way readers would mistake darker-skinned Drew for Jordan, for example — as the graphic novel format subtly and effectively reinforces the microaggression story line.

Many popular graphic novels are actually graphic memoirs, based on their creators’ own lives. Raina Telgemeier, Shannon Hale, Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm, Cece Bell, Vera Brosgol — all of these creators tell their own stories (or fictionalized versions) of their early adolescence through imagery that rings true to middle graders’ experiences, or to those on the cusp. (“What’s puberty again?” asked my own young graphic-novel fiend after recently tearing through Best Friends, illustrated by LeUyen Pham, about Hale’s sixth-grade year, including tricky friend dynamics, changing bodies, and some very tame kissing.) Comics can be an excellent creative vehicle for these types of adolescent quandaries, with dialogue perhaps saying one thing but pictures conveying something else; in Hale’s book, for example, stoic Shannon’s quivering chin gives her hurt feelings away. Telgemeier’s latest “Telgememoir” (H/T Shoshana Flax), Guts, effectively incorporates visual metaphor — with the image of fourth grader Raina, sick at school, shown trapped by a swirling green background. A reader must put all the pieces together, in text and art, in order to process what’s going on in a pubescent or prepubescent character’s head, simultaneously reading between the lines of the pictures that are in front of their eyes. That these creators have come out the other side of adolescence and are able to process their experiences and channel them into art gives middle graders some guideposts to the experiences.

Many popular graphic novels are actually graphic memoirs, based on their creators’ own lives. Raina Telgemeier, Shannon Hale, Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm, Cece Bell, Vera Brosgol — all of these creators tell their own stories (or fictionalized versions) of their early adolescence through imagery that rings true to middle graders’ experiences, or to those on the cusp. (“What’s puberty again?” asked my own young graphic-novel fiend after recently tearing through Best Friends, illustrated by LeUyen Pham, about Hale’s sixth-grade year, including tricky friend dynamics, changing bodies, and some very tame kissing.) Comics can be an excellent creative vehicle for these types of adolescent quandaries, with dialogue perhaps saying one thing but pictures conveying something else; in Hale’s book, for example, stoic Shannon’s quivering chin gives her hurt feelings away. Telgemeier’s latest “Telgememoir” (H/T Shoshana Flax), Guts, effectively incorporates visual metaphor — with the image of fourth grader Raina, sick at school, shown trapped by a swirling green background. A reader must put all the pieces together, in text and art, in order to process what’s going on in a pubescent or prepubescent character’s head, simultaneously reading between the lines of the pictures that are in front of their eyes. That these creators have come out the other side of adolescence and are able to process their experiences and channel them into art gives middle graders some guideposts to the experiences.

Interestingly, many graphic novels and memoirs are by #OwnVoices creators and are telling #DiverseBooks stories. Gene Luen Yang’s 2019 Zena Sutherland Lecture delves into the history of Asian Americans as well as Jews in comics. An October 2019 Teen Vogue article — “Latinx People Helped Build the World of Comic Books — While Often Being Left Out of the Pages” — discusses Latinx creators’ contributions. Even before #WeNeedDiverseBooks, there was a flourishing movement of experimentation in graphic novels by in-group creators about their own cultures published by mainstream children’s book presses. Yang’s diptych Boxers and Saints, for example, was experimental in both form and subject matter — a matched set of books, with magic, some humor, and heft, set during China’s Boxer Rebellion and starring protagonists on opposite sides of the conflict. Raúl the Third’s Lowriders series, written by Cathy Camper, and Barry Deutsch’s Hereville books spotlighted cultures rarely, if ever, seen in mainstream conventional children’s publishing (Latinx lowrider culture and Orthodox Judaism, respectively). Perhaps it’s because the form itself has been historically viewed as experimental…but whatever the reason, graphic novels have been a consistent source of welcome diversity in children’s publishing.

Interestingly, many graphic novels and memoirs are by #OwnVoices creators and are telling #DiverseBooks stories. Gene Luen Yang’s 2019 Zena Sutherland Lecture delves into the history of Asian Americans as well as Jews in comics. An October 2019 Teen Vogue article — “Latinx People Helped Build the World of Comic Books — While Often Being Left Out of the Pages” — discusses Latinx creators’ contributions. Even before #WeNeedDiverseBooks, there was a flourishing movement of experimentation in graphic novels by in-group creators about their own cultures published by mainstream children’s book presses. Yang’s diptych Boxers and Saints, for example, was experimental in both form and subject matter — a matched set of books, with magic, some humor, and heft, set during China’s Boxer Rebellion and starring protagonists on opposite sides of the conflict. Raúl the Third’s Lowriders series, written by Cathy Camper, and Barry Deutsch’s Hereville books spotlighted cultures rarely, if ever, seen in mainstream conventional children’s publishing (Latinx lowrider culture and Orthodox Judaism, respectively). Perhaps it’s because the form itself has been historically viewed as experimental…but whatever the reason, graphic novels have been a consistent source of welcome diversity in children’s publishing.

Graphic novels for middle graders have a unique position for some readers, situated between picture books and non-illustrated works and straddling subject matter suitable for their developmental position between young childhood and young adulthood. Whether fluent, emergent, reluctant, or in between, a reader’s reading of a book can depend on format and accessibility. Of course kids’ love of graphic novels doesn’t necessarily have to be tied to developmental milestones; many middle graders love graphic novels for their own sake, not just as a gateway between picture books and non-illustrated novels. It’s easy to see why: action, adventure, humor, emotion — everything that makes a good middle-grade book good — can all be found (and seen) in today’s expansive library of graphic novels.

From the March/April 2020 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

![]()

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!