When you look at others, what do you assume? When others look at you, what do they see? These questions lie at the heart of Milo Imagines the World. Christian Robinson has illustrated the book in two styles: his artwork stands apart stylistically and spatially from the drawings purportedly by Milo, the story’s young African American protagonist.

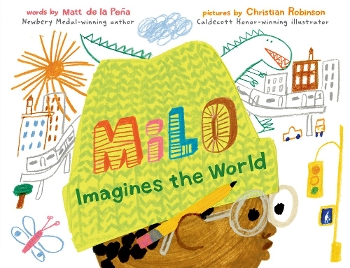

When you look at others, what do you assume? When others look at you, what do they see? These questions lie at the heart of Milo Imagine the World, written by Matt de la Peña. Christian Robinson has illustrated this book in two styles: his artwork stands apart stylistically and spatially from the drawings of Milo, the story’s young African American artist and protagonist. Wearing distinctive big round eyeglasses and a bright green winter hat, Milo and his unnamed teenaged big sister take the New York subway to a destination — we read that they do this monthly — that remains a mystery until nearly the end of the story. The narrator describes himself as “a shook-up soda” early in the story, when readers cannot discern whether this refers to the physical turbulence of riding the subway or the emotional upheaval related to their destination. As the diverse riders enter the train, Milo draws them in his spiral sketchbook, creating a life for them that involves both his imagination and many assumptions — some positive, some less so.

When you look at others, what do you assume? When others look at you, what do they see? These questions lie at the heart of Milo Imagine the World, written by Matt de la Peña. Christian Robinson has illustrated this book in two styles: his artwork stands apart stylistically and spatially from the drawings of Milo, the story’s young African American artist and protagonist. Wearing distinctive big round eyeglasses and a bright green winter hat, Milo and his unnamed teenaged big sister take the New York subway to a destination — we read that they do this monthly — that remains a mystery until nearly the end of the story. The narrator describes himself as “a shook-up soda” early in the story, when readers cannot discern whether this refers to the physical turbulence of riding the subway or the emotional upheaval related to their destination. As the diverse riders enter the train, Milo draws them in his spiral sketchbook, creating a life for them that involves both his imagination and many assumptions — some positive, some less so.

For the man sitting next to him, reading the newspaper and completing the crossword, Milo initially imagines him returning home through brown sludge to his cluttered sixth-floor apartment, three escaped parakeets, three cats, “burrowing rats,” and a lonely dinner of “tepid soup.” Milo also predicts a heterosexual wedding for a blue-haired, dark-skinned woman, who carries a flower bouquet and a small tan dog with a lolling tongue in a shoulder bag. Milo’s primary curiosity, however, focuses on a White boy with bright white Nikes, wearing a suit jacket and tie; he enters with a man Milo speculates is his father. In Milo’s imaginative conjecture, this boy goes home to a castle, where his sizable staff eagerly awaits his arrival, lowering the drawbridge for him and bringing him crust-free sandwiches.

The scenes Milo invents for the lives of the train riders appear in double-page, landscape spreads (with the spiral middle showing in the gutter), alternating with Robinson’s double-page spreads of Milo’s actual journey. The exception to this page layout signals an important turning point in the story. When Milo attempts to get his sister’s attention to show her his drawings, she and Milo appear on the left page, with a rear view of the suit-wearing boy to the far left, but on the right page, Robinson splits the top and bottom of the page with a white line, showing Milo above and the boy below, both positioned just right of center. “They lock eyes for a few seconds, and suddenly it feels like the walls are closing in around Milo.” Prior to this moment, Milo has had the luxury of watching without being watched. When he realizes that he has captured the other boy’s undivided attention, an uncomfortable moment of inward gazing occurs for Milo. After a group of break-dancers interrupts his contemplation, Milo puts his sketchbook in the seat next to him and turns to the blackened window-turned-mirror. He wonders then: “What do people imagine about his face?” This question prompts a new illustration and several questions about what others might assume about his life: can they see his studiousness? Can they hear “his mom’s soothing voice reading him a bedtime book over the phone?” (This may promp readers to ask where his mother is and why she must read to him via phone.) Can they smell the delicious foods his aunt cooks in her apartment? (This might also raise the question of why he lives with his aunt.) Clearly, he wants others to see him in a positive light, which changes everything for Milo, prompting re-illustrations of all the travelers he has drawn previously, including creating a same-sex wedding for the blue-haired woman.

Milo has yet another shift in perspective when he and his sister exit the train and he realizes that the suit-wearing boy and his dad have the same destination as Milo and his sister: through a security checkpoint and into the prison to visit a relative. As Milo and his sister greet their mother, wearing the same orange outfit as the other prisoners, the suited boy also seems to be visiting his mother. One then wonders how Milo might be remapping his royal assumptions about the life of this well-dressed White boy. Despite the fact that a security guard with gun-bearing holsters looks on, observing four reunions, here “in this tight tangle of familiar arms” Milo “feels most alive.” He proudly shows his mother the artwork he has sketched for her, which readers have not yet seen, and he “watches for the smile he hopes will spread across his mom’s face.” A double-page spread then reveals his mom, his big sister, and Milo (between them), sitting on the front stoop of their house, eating ice cream cones. His big sister’s braids and Milo’s glasses, drawn with Milo’s vibrant colored pencils, make the identities of the characters unmistakable, but the smiles on their faces during this poignant reunion tell the most anticipated part of Milo’s story.

Many fine details in Robinson’s art reward readers who pay close attention. The book’s front and rear endpapers have the same horizontal zigzag pattern as Milo’s hat, pointing out that the best parts of this book emerge from inside Milo’s head (and imagination), covered by that capacious cap. Curiously, Milo’s colorful drawings on the left side of the title page show a parade of people walking down the street with a butterfly and two birds flying around but also with animals unlikely to appear on a city street: a giraffe, a rhino, and a flamingo on a leash, held by someone wearing a green ballcap and bowtie. A green, city-dwelling dinosaur and a rocket ship, also clearly Milo’s creations, appear on the book jacket. These fantastic additions contrast with the mostly realistic portrayals Milo creates for the subway riders. Even the boy who Milo assumes lives in a castle only gains a higher socioeconomic status, not a life of fantasy, through Milo’s drawings. Perhaps this points to the expansiveness of Milo’s imagination, vaster and more impressive than what this one story can contain.

A notable aspect of this mixed-media and collage book is that two male creators of color bring to life a sensitive, observant, artistic boy of color who has a fascinating life of the mind and whose imagination not only keeps him positively engaged when being a “shook-up soda” could get the better of him, but it also projects a similar life trajectory for Milo as his creators have had. He could grow up to be a writer like De la Peña or an artist like Robinson (or both!), and that’s inspiration worth taking away from this amazing, honest, and exquisitely crafted picture book.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Milo Imagines the World here.]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!