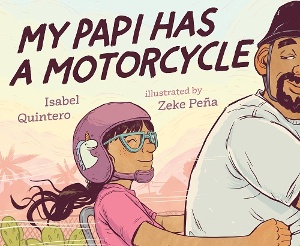

Isabel Quintero and I have at least one thing in common. My Papi Has a Motorcycle, too, and although we used to ride on Sunday mornings instead of in the evenings, Quintero and I both know the bond-forming experience of a father sharing the road with his daughter. Quintero once again collaborates with illustrator Zeke Peña (they worked together on Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbe), telling the story of a memorable motorcycle ride that Daisy and her father take through their hometown of Corona, California.

Isabel Quintero and I have at least one thing in common. My Papi Has a Motorcycle, too, and although we used to ride on Sunday mornings instead of in the evenings, Quintero and I both know the bond-forming experience of a father sharing the road with his daughter. Quintero once again collaborates with illustrator Zeke Peña (they worked together on Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbe), telling the story of a memorable motorcycle ride that Daisy and her father take through their hometown of Corona, California.

Isabel Quintero and I have at least one thing in common. My Papi Has a Motorcycle, too, and although we used to ride on Sunday mornings instead of in the evenings, Quintero and I both know the bond-forming experience of a father sharing the road with his daughter. Quintero once again collaborates with illustrator Zeke Peña (they worked together on Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbe), telling the story of a memorable motorcycle ride that Daisy and her father take through their hometown of Corona, California.

The endpapers show the town — nestled at the foot of a mountain, sitting quietly, and about to be stirred up by our speeding duo. The thrill and enjoyment from the ride that is to come is already visible in the wind lines shown on the cover. As the first spread introduces Daisy, waiting in the garage for her papi, digging through an open tool box, an exclamation point breaks a panel — Peña makes use of elements commonly found in graphic novels — telling us that something big is coming. Daisy runs outside ("WOOSHHH") in excitement, both helmets in hand, to greet Papi. (In an interview with NPR, Quintero mentions that no helmets were actually used during her own 1980s-era rides, but she felt they had to be in the story.)

Peña’s attentiveness to the details in his illustrations, which add so much to the sensory experience of reading the book, prevails throughout. His style is warm and vibrant. His line strokes are loose and free, as if they escaped Peña’s hand as fast as the bike. With a colorful palette, consisting of mostly soft, warm colors, this book provides the feeling of a memory being made. However, this is in no way a nostalgic, static book.

Once helmets are in place, tightened by Papi’s large yet delicate hands, Daisy and Papi VROOOOOMM out of the driveway. A stunning spread — with a zigzag of blue and an explosion of vibrant pink, yellow, and orange — announces a change in gear. The pair takes a whirlwind tour around the town, and sights like a tortillería, Abuelita’s church, and a local supermarket fill the pages.

As I shared Peña’s work with my mom, she said, “Es uno de esos libros que te quieres detener a ver todo.” I immediately agreed with her, as I too wanted to savor every detail in the book. Although the illustrations aren’t intricate, as in a Wiesner or a Pinkney book, they are full of particulars that ground the reading and the experience of zipping through streets. Peña captures the smallest details that reverberate in the biggest ways. With the lopsided gumball/toy dispenser and the hanging piñatas outside Joy’s Market, I am transported back to any and all “tienditas de la esquina” and can smell the meats and pan dulce advertised on the wall — although the strawberry concha’s frosting seemed a little stingy for my taste. Continuing through the book, we see a paletero on his bicycle selling Tweety Bird and Ninja Turtles ice-cream bars. Back home, there's a coffee can on the porch that doubles as a planter, probably containing aloe to apply in case of burns. All authentic details that allow young readers to see their own lives in the illustrations.

My Papi Has a Motorcycle also performs quiet, informative work. Through murals, popular in Mexican American art, the collective community history is depicted. The murals in Corona, a town crucial to citrus production, depict immigrant workers picking lemons and the Corona race of 1913, which Daisy longs to be a part of. The palette gives a sense of old-timeliness yet is vibrant enough to keep it fresh and innovative. The book also addresses loss, in the form of Don Rudy’s raspados shop. The shaved ice-cream store is all boarded up in a spread in which Peña cleverly hides Papi and Daisy’s faces. We do not partake in their sadness and regret, except when Daisy turns back and takes one longing last look.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of My Papi Has a Motorcycle.]

One of the Caldecott committee criteria talks about providing a “visual experience” for a child. Peña’s illustrations in My Papi Has a Motorcycle go beyond, as they evoke multisensory experiences. Some of the most stunning pictorial depictions in the book are the onomatopoeias. Sounds and movement — the rumbling vibrations of a lawnmower, the screech of brakes — are cleverly presented in hand-lettering in Peña’s pencil strokes. You can almost feel the vibrations of a revving bike or a jackhammer at work. You can almost hear the norteño music coming from the radio and the hammering of the construction crew. And don’t forget the bilingual aspect in onomatopoeias, as cats meow and miau, dogs woof and guau, and people laugh in English (hahaha) and Spanish (jajaja). (For some reason, birds are monolingual and only chirp.)

I truly hope that the Caldecott committee takes the time to consider the care Peña took in crafting the sensory experiences, so expertly translated into the illustrations — illustrations that make this a Caldecott-worthy book.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Nina Armendariz

I love the article... It made me want to read the book. Every book you recommend is worth reading.Posted : Nov 09, 2019 08:30