Holocaust picture books usually lie, with their omissions and happy endings. They trade in metaphor. They de-emphasize Jewishness. They revel in Anne Frank’s “I still believe that people are good at heart” and bypass her “I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever-approaching thunder, which will destroy us too.” And yet here I am, arguing that Peter Sís's Nicky & Vera deserves Caldecott consideration.

I loathe the widespread critical overuse of the word luminous. But what other adjective can you use for the illustrations of Peter Sís? Lyrical? Ethereal? Clichés too! Also true! Grr.

I loathe the widespread critical overuse of the word luminous. But what other adjective can you use for the illustrations of Peter Sís? Lyrical? Ethereal? Clichés too! Also true! Grr.

And another cliché: “A singular talent.” But three Caldecott Honors (for 1997’s Starry Messenger, 1999’s Tibet Through the Red Box, and 2008’s The Wall: Growing Up Behind the Iron Curtain), a gazillion Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards, a passel of New York Times-New York Public Library Best Illustrated Children’s Book awards, a MacArthur “Genius Grant” (the first children’s book illustrator ever so honored), and many more honors attest to that truth, too.

And yet. I did not want to like this book.

This is a picture book about the Holocaust. Most middle-grade and young-adult Holocaust books fail — they’re sentimental, ponderous, poorly researched, skewed, pedantic, simplistic, opportunistic, or torture porn-y — and picture books are usually worse. Experts in teaching Holocaust literature warn that books for young readers need to be authentic, age-appropriate, readable, and emotionally immediate without being traumatizing. I’d add that they also have to be wary of overemphasizing righteous gentiles and ending on a too-optimistic note.

Holocaust picture books usually lie, with their omissions and happy endings. They trade in metaphor. They de-emphasize Jewishness. They are narrated by cats or trees. They revel in Anne Frank’s “I still believe that people are good at heart” and bypass her “I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever-approaching thunder, which will destroy us too.”

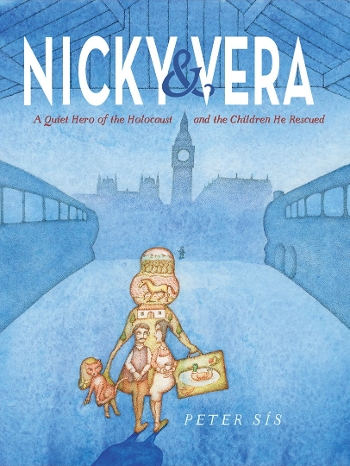

And yet here I am, arguing that Nicky & Vera: A Quiet Hero of the Holocaust and the Children He Rescued deserves Caldecott consideration. Visually, Sís is at the top of his game. Nicky & Vera employs his characteristic maps, mazes, graphic borders, stamps, and circles and his gorgeous washes of watercolor with semi-submerged, mysterious, pen-and-ink illustrations half-hidden within them; these hallmarks are particularly apt in a story about a border-crossing, document-forging, labyrinthine wartime rescue effort.

Nicky & Vera tells the true stories of Nicholas "Nicky" Winton, a young Brit who helped mastermind the rescue of Czech Jewish children via trains to England, and Vera Gissing, one of the children he rescued. Their narratives remain separate until nearly the end of the book, when the characters meet and their stories intertwine.

Sís’s use of form and color is, as ever, masterful. Take this spread, depicting little Vera all alone in a London train station awaiting her “new family.” The double-peaked, plank roof taking up the top third of the spread is all straight lines — dozens and dozens of them, in somber parallel slats. They echo the straight lines of the train, which is disappearing into the vanishing point of the horizon in the middle of the spread. The train is gray, full of infinitely precise and subtle cross-hatching —still more straight lines. The angled roof and empty station are awash in moody, cloudy, watercolor blues. Left behind in the station, and in the bottom third of the spread, is Vera. She’s standing in the left foreground, clutching a little suitcase in one hand and her dolly’s hand in the other. She is the only curvilinear form in this chilly world, drawn in an entirely different color palette of yellows, pinks, and pale greens. She is a silhouette, filled with the warm, beautiful rural life she’s left behind: trees, ducks, a horse, a cozily set table, one of her beloved cats, and largest of all, her smiling parents.

In another spread further along in the story, the now-elderly Nicholas Winton — who’d told almost no one about his secret rescue missions during the war — is surrounded by some of the 669 now-middle-aged children he rescued. They’re all standing, most in profile, all angled to look at the seated Winton. Every former child is filled with a gentle gray cloud of watercolor (Vera, standing closest to Winton, has subtly deeper gray coloring, drawing your eye to her; Winton's eyes are pointed just slightly toward her, too), and inside each body of each former refugee is a tiny sepia-toned child, a depiction of who they were when they were rescued.

I’m aware that the Caldecott Medal is for illustration. (I’m also aware that this is a constant source of debate.) There should be no question that Sís’s artistic work is “distinguished”; the art is astonishing and beautifully complements the simple, declarative text. It seems to be irrelevant in terms of the award criteria that Sís has accomplished something remarkable and rare, telling a Holocaust story in picture book format that isn’t dumbed down or pedagogically unsound. He spells out that Vera’s entire family died; this is important. We also read that, after the war, she "only found the daughter of one of her old cats.” This hits hard. It’s reinforced by the graphite-colored cat and Vera’s hair as the only solid-looking touches in a pale spread full of empty paths, ghost houses, gravestones, unreadable writing, and wispily drawn echoes of all the quotidian things — teacups, alarm clocks, books, photos — that Vera has lost. (I do wish someone had thought to transpose the words only and found in that sentence, because grammar, but I will let this go.) The back matter, too, is solid and well-sourced.

There are elements of the text I could quibble with. (Buy me a drink and I will.) But the art is unimpeachable, and given that we live in a world of rising anti-Jewish sentiment and violence, one in which twenty-two percent of millennials have never heard of the Holocaust, Nicky & Vera is important as well as visually spectacular.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Nicky & Vera here.]

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!