On the Futurity of the Pura Belpré Award

A reflection on the future of the Pura Belpré Award must begin with a meditation on the past. As Black, Caribbean, Afro-Atlantic, and Afro-Latinx scholars teach us, the future is in the past, and the present is in the future. My contemplation, then, begins with two iconic photographs of Pura Belpré.

A reflection on the future of the Pura Belpré Award must begin with a meditation on the past. As Black, Caribbean, Afro-Atlantic, and Afro-Latinx scholars teach us, the future is in the past, and the present is in the future. My contemplation, then, begins with two iconic photographs of Pura Belpré.

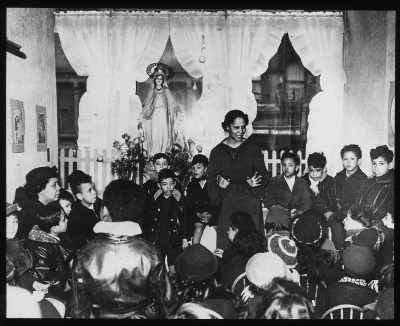

Storytelling at the 115th Street Library (left) and El Museo del Barrio (above).

Pura is performing storytimes with Black and Boricua children in New York City. The punctum of both pictures is her hands. Pura Teresa Belpré’s hands speak to me; they touch me. They disrupt the linearity of colonial time that would seek to fix us and freeze us into the past. They emit the sounds made en la brega, vibrating with the improvisations and everyday inventions that Boricuas do to resist and refuse the ongoing assault of empire’s violence.

In Listening to Images, Tina M. Campt examines the genre of “identification photography” — passport photos, ID cards, etc. — particularly in their governmentality of Black people in diaspora. While the primary purpose of identification photography may be to operationalize the workings of the institution, their subjects’ vitality gives voice to their experiences. These archival photographs, Campt argues, bear witness to the ordinary, everyday practices of Black diasporic life — practices of the quotidian which we may otherwise miss in their ordinariness. Campt theorizes a way to, counterintuitively, “listen” to photographs, and thus attune to the “quotidian reclamations of interiority, dignity, and refusal marshaled by black subjects in their persistent striving for futurity.”

In many ways, these images of Belpré operate as identification photography in that they archive the workings of the New York Public Library’s storytime programming for Harlem and East Harlem’s children of color throughout her tenure. The photographs serve as records of Belpré’s innovations in culturally sustaining library programming and community outreach that centered the linguistic beauty of Spanish and bilingual storytelling, puppet theater production, and visual and performing arts and literacy that put Black and Puerto Rican children at the heart of the NYPL. A polyglot and gifted storyteller, Belpré wrote and published extensive collections of Puerto Rican folktales throughout a monumental, generative career of sixty-seven years of professional library service that spanned most of the twentieth century and that continues to influence and expand our contemporary understanding of library services for children.

Near the end of her decades-long career as a children’s librarian, Belpré began writing a series of essays describing her everyday work, in which she articulated her vision for the transformative possibilities in storytelling, its humanizing dignity, and its ethical imperative to exceed the restricted possibilities created for children of color by the state. Collected in Lisa Sánchez González’s comprehensive critical biography, The Stories I Read to the Children: The Life and Writing of Pura Belpré, the Legendary Storyteller, Children’s Author, and New York Public Librarian, are Belpré’s words:

In this present struggle to fight poverty, hunger and fear, and to bring some semblance of peace and security into the home, the need for serenity and beauty seem to be forgotten. Food alone can’t do it. It needs an elevation of the spirit that transcends all materialities. This serenity, this beauty, is apparent in the faces of the children in the story hour room. For a while at least, through the power of a story and the beauty of its language, the child escapes to a world of his own. He leaves the room richer than when he entered it.

Belpré’s contemporary Arturo Alfonso Schomburg also identified the role of storytelling in perpetuating Black and Afro-Latinx vitality in his call to arms, that books “about black history and culture…‘must be published, and it is the responsibility of you and other children’s librarians to get them written and published.’” Augusta Baker and Charlemae Hill Rollins, likewise contemporaries of Belpré, activated this very imperative in their curation and dissemination of bibliographies of African American children’s literature. Tracing the genealogies of Black and Boricua librarianship in this way allows us to see how the vision and path-making of Glyndon Flynt Greer and Mabel R. McKissick — founders of the Coretta Scott King Book Award — also directly shaped and inspired the work of Chicana and Latina children’s librarians Sandra Ríos Balderrama and Oralia Garza de Cortés. Their impulse to change the institutional shape of children’s literature awards, and, in turn, youth services librarianship and the world of youth literature publishing, led to their establishment of the Pura Belpré Award.

The Coretta Scott King Book Award and the Pura Belpré Award have gained authority and visibility by operating within the existing professional institutions of children’s librarianship and publishing markets. Indeed, the Pura Belpré Award has gained firm institutional ground since its establishment twenty-five years ago. That its taproot continues to survive and persist against the hubristic “slippery slopes” of whiteness is evident in the expansion of the award to now include Latinx-authored young adult literature, the growing momentum of scholarship on Latinx youth literature, as well as attention to the historiography of Belpré’s far-reaching contributions to librarianship, education, and children’s literature.

Yet the disparity in children’s literature by and about people of color and white people persists, as the Cooperative Children’s Book Center reminds us each year. The dominance of white authorship in youth literature continues to assert structures of white supremacy across all facets comprising the networks of youth literature. As Marilisa Jiménez García writes in her essay “The Pura Belpré Medal: The Latino/a Child in America, the ‘Need’ for Diversity, and Name-branding Latinidad”: “We need more than diverse books and even more than diverse book prizes. We need a field of children’s literature — English departments, educators, libraries, and publishers — that includes people of color. And we need antiracist mechanisms that push past the narrow affirmations of literary distinction.”

Perhaps it is here, en la brega of youth literature publishing and prizing, where we can attune to the sounds of Pura Belpré’s hands, for these hands hold a key that unlocks the infinite ways for us to keep on pushing, to keep on making, to keep on writing and telling our stories. As Belpré herself revealed in the documentary Pura Belpré, Storyteller by Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños: “The first story that I heard from my grandmother’s lips was ‘La Cucarachita Martina y el Ratoncito Pérez.’ Perez and Martina has been my golden key. It’s been opening doors for me, everywhere.” The magnitude of Belpré’s contributions, and how her legacy continues to unfold through the Belpré Award, is to be understood through the ongoing work of librarians, scholars, educators, parents, caretakers, children, young people, writers, and illustrators situated in the wide diaspora of Afro-Latinx life.

It matters profoundly that Pura Belpré was born in Cidra, Puerto Rico, and that hers was a life of the Black Puerto Rican diaspora. The stories we award under her name have an opportunity to disrupt Latinx representation under a white gaze. Antiblackness permeates Latinidad’s investments in mestizaje, the colonial racialized logics of assimilation, and stories of progress that devalue nonwhite people.

What might it mean, then, to consider a futurity for the Belpré Award that pushes against the normativity of the white dominant culture? To refigure our prize committees toward a rejection of Western canons in our assessment of literary and artistic quality, to instead engage in the capacious aesthetics that recognize the vitality of Black, Boricua, Afro-Latinx diasporic life? What if instead of a seat at the table, we were to actualize the Belpré Award as a site of rehearsal and imagination outside of empire?

Today, as I listen and attune to the register of the sounds and vibrations emitting from the photographs of Pura Belpré, I hear the charge in these questions. And Belpré’s hands, much like they moved the children who heard her stories, move me, too! To dream up worlds of boundless imagination and without restriction, new worlds in which to tell our stories, about how we make beauty from life in the face of death.

From the May/June 2021 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Pura Belpré Award at 25. Above left: photo courtesy of New York Public Library Archives, The New York Public Library. Above right: Photo courtesy of the Pura Belpré Papers, 1897-1985 collection at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives. Hunter College, City University of New York.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!