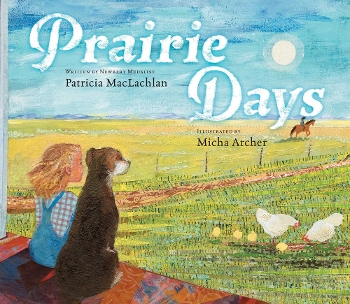

In Patricia MacLachlan's Prairie Days, illustrated by Micha Archer, poetry and picture come together to create a book that provides children with a "visual experience” that is altogether mesmerizing and worthy of the 2021 Caldecott Medal.

Every August, I replace my Caldecott poster with the updated version. Strategically placed near my circulation desk and next to the Caldecott award shelf, it hangs low to the ground to ensure comfortable viewing for even the youngest of students. At the top of the poster is the cover of the most recent Caldecott winner and beneath it are the covers of all eighty-three Caldecott Award winning books. Children are fascinated with the poster, and I often overhear them identifying and comparing favorites with classmates. I have at least one copy of every Caldecott Medal winner and often have designated “Caldecott Conversation” weeks when students select a medal-winning book and study it with a buddy. I encourage children to choose new-to-them winners, but often they want to revisit their favorites. Peggy Rathman’s Officer Buckle and Gloria, Leo and Diane Dillon’s Why Mosquitos Buzz in People’s Ears, Allen Say’s Grandfather’s Journey, Emily Arnold McCully’s Mirette on the High Wire, Virginia Lee Burton’s The Little House — these, among others, are in frequent rotation.

Every August, I replace my Caldecott poster with the updated version. Strategically placed near my circulation desk and next to the Caldecott award shelf, it hangs low to the ground to ensure comfortable viewing for even the youngest of students. At the top of the poster is the cover of the most recent Caldecott winner and beneath it are the covers of all eighty-three Caldecott Award winning books. Children are fascinated with the poster, and I often overhear them identifying and comparing favorites with classmates. I have at least one copy of every Caldecott Medal winner and often have designated “Caldecott Conversation” weeks when students select a medal-winning book and study it with a buddy. I encourage children to choose new-to-them winners, but often they want to revisit their favorites. Peggy Rathman’s Officer Buckle and Gloria, Leo and Diane Dillon’s Why Mosquitos Buzz in People’s Ears, Allen Say’s Grandfather’s Journey, Emily Arnold McCully’s Mirette on the High Wire, Virginia Lee Burton’s The Little House — these, among others, are in frequent rotation.

I, too, love looking at the poster, tracing eight decades of distinguished picture books. I always find myself wondering, What makes some Caldecott Award winners memorable and others, to put it bluntly, forgettable? Picture the cover of Robert McCloskey’s Make Way for Ducklings (winner of the 1942 medal). Okay, now picture the cover of Nonny Hogrogian’s Always Room for One More (winner of the 1965 medal). Can you do it?

In Patricia MacLachlan and Micha Archer’s collaboration, Prairie Days — I have hopes we'll see this one on that poster soon — poetry and picture come together to create a book that provides children with a "visual experience” that is altogether mesmerizing and worthy of the 2021 Caldecott Medal — and definitely memorable. Let's look at why, point by point, according to the Caldecott criteria.

Excellence of execution in the artistic technique employed:

The collage illustrations are a combination of acrylics, inks, and textured papers that Micha creates using origami, tissue papers, and homemade stamps. From the sunny yellow front endpapers to the dark midnight-hued back endpapers, each page invites readers to linger and notice the layers of textures and pattern that come together to create cohesive prairie-scapes, with children, storekeepers, grandmothers, and farm dogs nestled within. Collage illustrations can be busy, adding an element of the chaotic, but Archer keeps this from happening by balancing collage with portions of acrylic paint. For example, on one of the spreads, the children, wooden porch, Papa’s old gray car, filling station buildings, and the golden prairie fields are painted paper collages, causing them to pop against the wide dirt road and blue sky, which are rendered in acrylics textured with brush stroke.

Appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme, or concept:

The prairie’s endless horizon and “sky so big” are captured through Archer’s double-page spreads filled with wide-angle perspectives, showing long dirt roads, fields with rows of crops, railroad tracks stretching into the distance, a wide front porch and the place “where the prairie met the mountains.” Archer’s use of mixed media (lace for the curtains, cotton for the clouds, etc.) complement, but do not overwhelm, MacLachlan’s gentle reminiscences, reflecting breezy summer days, the prairie’s patchwork landscape, and “quilts of stars, pinwheels, and squares.”

Delineation of plot, theme, characters, setting mood or information through the pictures:

Archer’s illustrations add humanity and a sense of time and place, lifting the poem from a memory to a story. Like the 1980 Caldecott winner — Donald Hall and Barbara Cooney's Ox-Cart Man, which I always turn to every March when I have the the obligatory district-mandated task privilege of teaching economic principles to six-year-olds — one grasps the time period (1940s or 1950s) through the illustrations. There are 1940s-era automobiles; children get drinks “out of cold-water lift top tanks” and buy “penny mints” at the town’s general store, where colorful bolts of fabric sit behind the counter. Could the barrel of brooms be a nod to Ox-Cart Man?

Excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience:

My first Prairie Days read-aloud experience was with college students in the context of a picture-book course. They commented on the depth of Archer’s illustrations, the effect of rubber stamps, the sunset’s warm hues, and how horizon lines work. A week later, I read it aloud to a group of (masked) second-graders. When I closed the book, it was quiet. I found myself whispering my normal post-read discussion questions, and my students whispered back. Their comments were different than my college students' — but equally astute. They noticed the farm dogs, the old-fashioned cash register, and vintage catalogue images; the subtle patterns found in the golden fields, shimmering pond, and layered night sky; and how the red barn casts a blue shadow. Then the connections started and their whispers grew to chatter, as they compared the story to their summers spent at the lake or shared how their grandmother has hollyhocks in her garden. One commented, “It reminds me of my mom’s scrapbook and, Miss Stuart, can we use your origami paper and punches to make pictures of our special places? I want to make my backyard forest.” MacLachlan’s words and Archer’s art captivated the children, showing them another place and time and inspiring them to consider, connect, and create.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Prairie Days here]

Words are abstract, but images are concrete. Here, Micha Archer takes a poem and brings it to life. Offering more than just defining images, she gives children a rich visual feast, transporting them back in time to experience sun-splashed prairie days. It’s majestic, mesmerizing, and marked with eminence, yes. And guess what else it is?

Memorable.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!