Reviews of the 2020 Sibert Award winners

Read the Horn Book's reviews of the 2020 Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award winner and honorees.

Winner

Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story

Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story

by Kevin Noble Maillard; illus. by Juana Martinez-Neal

Preschool, Primary Roaring Brook 48 pp.

10/19 978-1-62672-746-5 $18.99

This affectionate picture book depicts an intergenerational group of Native American family members and friends as they make fry bread together. The text begins: “Fry bread is food / Flour, salt, water / Cornmeal, baking powder / perhaps milk, maybe sugar.” On subsequent pages we learn that “Fry bread is shape…sound…color,” etc.; and through the refrain “Fry bread is…” readers learn that the food staple, although common to many Native American homes, is as varied as the people who make it and the places where it is made. This diversity, too, is reflected in Martinez-Neal’s warmhearted acrylic, colored-pencil, and graphite illustrations, on hand-textured paper, in which the characters within Native American communities have varying skin tones and hair texture. More than just food, “Fry bread is time…Fry bread is art…Fry bread is history.” In the extensive, informative back matter, Maillard (a member of the Seminole Nation, Mekusukey band) explains how fry bread became a part of many Native Americans’ diet after the people were forced from their land and given limited rations by the United States government. The book’s endpapers powerfully list the names of Indigenous communities and nations currently within the U.S., some federally recognized, others not. Regardless of “official” status — as the book declares — “We are still here.” Reference list and notes — plus a recipe — are appended. NICHOLL DENICE MONTGOMERY

From the November/December 2019 Horn Book Magazine.

Honor Books

All in a Drop: How Antony van Leeuwenhoek Discovered an Invisible World

All in a Drop: How Antony van Leeuwenhoek Discovered an Invisible World

by Lori Alexander; illus. by Vivien Mildenberger

Intermediate Houghton 94 pp.

8/19 978-1-328-88420-6 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-0-358-03619-7 $9.99

In the prosperous city of Delft, in seventeenth-century Netherlands, Antony van Leeuwenhoek was a cloth merchant. But even without formal scientific training, and possessing abundant curiosity and technical skill, Antony became instead interested in lenses and magnification. He went on to create the most advanced microscopes in the world, eventually amassing a collection of over five hundred, each affixed to an individual specimen. He was secretive about his cutting-edge technology, which allowed him to be the first person ever to see many varieties of microbes — which he called diertgens (little animals), translated into English as “animalcules.” Alexander’s excellent, accessible overview of Leeuwenhoek’s life gives upper-elementary chapter-book readers a feel for both the person and the historical context. Well-chosen quotes from Leeuwenhoek’s letters reveal the sometimes tentative but ultimately persistent pioneer and reflect a time when scientific inquiry was open and encouraging to those with the means to pursue their passions. Mildenberger’s cartoony illustrations, both spot art and full-page drawings, include intricately rendered details of the people, places, and microbes of Leeuwenhoek’s world. DANIELLE J. FORD

From the November/December 2019 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

This Promise of Change: One Girl’s Story in the Fight for School Equality

This Promise of Change: One Girl’s Story in the Fight for School Equality

by Jo Ann Allen Boyce and Debbie Levy

Intermediate, Middle School Bloomsbury 311 pp. g

1/19 978-1-68119-852-1 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-1-68119-853-8 $12.59

In 1956 in the small town of Clinton, Tennessee, twelve African American students integrated the all-white high school. Jo Ann Allen Boyce, one of the “Clinton 12,” narrates this first-person account. She lives with her family up on the Hill, a part of the city that was settled by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. Jo Ann and her family are active in their church, and her knowledge of religious songs and biblical history is threaded throughout the memoir. The book consists of free-verse passages that often include rhyme and employ various forms such as pantoum and villanelle. (One haiku titled “And Then There Are the Thumbtacks” reads: “Scattered on our chairs / A prank straight out of cartoons / They think we don’t look?”) Boyce’s character evolves throughout the book. Though not naive about racism early on, she later fully experiences the weight of white supremacy. Even her white neighbors on the Hill turn on her family members once they are perceived as stepping “out of their place.” Newspaper headlines and clips, excerpts from the Constitution, and examples of artifacts such as signs held by protesters (“We Won’t Go to School with Negroes”) are interspersed throughout. This fine addition to texts about the integration of public schools during the civil rights era in the United States concludes with an epilogue, biographical information about the Clinton 12, a scrapbook of photographs, source notes, and a timeline. JONDA C. MCNAIR

From the January/February 2019 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

Ordinary Hazards: A Memoir

by Nikki Grimes

High School Wordsong/Boyds Mills 325 pp.

10/19 978-1-62979-881-3 $19.99

As poetically written as Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming (rev. 9/14) with a story as hard-hitting as Sapphire’s Push. In her author’s note, poet Grimes (winner of the 2017 Children’s Literature Legacy Award) says that memoirs focus on truth, not fact. Because of the childhood trauma she suffered, she has limited memories of her early years but has constructed the truths of her life from a patchwork of recollections; photos obtained from friends and family; and a few artifacts salvaged despite the frequent moves of her impoverished family and time spent in foster care. Overshadowing most of the story, her mother’s mental illness (paranoid schizophrenia), alcoholism, and marriage to an abusive and irresponsible man made Grimes’s early life hazardous. In a childhood in which she had to elude rats in her apartments and bullies and gangs in her neighborhoods and in which she was sexually violated by her stepfather, young Nikki found solace and confidence through her identity as a writer. She was supported and nurtured by her sister, from whom she was separated at age five; by her father, a violinist who immersed Nikki in Harlem’s Black Arts scene; and by an English teacher who insisted on excellence. As her story unfolds (the book is arranged in sections, chronologically, beginning in 1950 and ending in 1966), the striking free-verse poems powerfully convey how a passion for writing fueled her will to survive and embrace her own resilience. “My spiral notebook bulges / with poems and prayers / and questions only God / can answer. / Rage burns the pages, / but better them / than me.” A must-read for aspiring writers. MONIQUE HARRIS

From the September/October 2019 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

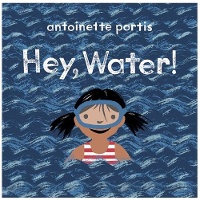

![]() Hey, Water!

Hey, Water!

by Antoinette Portis; illus. by the author

Preschool, Primary Porter/Holiday 48 pp. g

3/19 978-0-8234-4155-6 $17.99

e-book ed. 978-0-8234-4201-0 $17.99

A girl named Zoe explores water in this playful and informative book. Speaking directly to water (“Hey, water! I know you! You’re all around”), Zoe considers the role of water inside a home (shower, faucet) and outside of it (sprinkler, hose). Spread by spread, the book’s scope widens as the girl points out ever-larger bodies of water — from a stream to a river to an ocean. The scope then shrinks back again to a lake, pool, puddle, and dewdrop. Zoe also considers the different forms water can take (identified in the back matter as liquid, solid, and gas), using examples such as the steam of a teakettle, a cloud, an ice cube, and more; throughout, each item is accompanied by an unobtrusive label in a larger block font to help clarify the information. Portis’s main text is spare and accessible, with occasional, effective use of figurative language: dewdrops that wink, water that freezes “soft as a feather,” snowflakes that are “fancier than lace.” The many permutations of water (not the book’s protagonist) are the focus of the crisp, uncluttered, primarily aqua-colored illustrations; when we do see Zoe, she’s delighting in water. “Hey, water, thank you!” she says on the final page while playing in the bathtub. The story’s ending segues easily to back matter that includes notes on conservation and water forms and a simple diagram of the water cycle. JULIE DANIELSON

From the March/April 2019 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

For more, click on the tag ALA Midwinter 2020.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!