Sarwat Chadda Talks with Roger

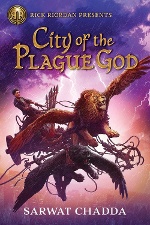

In City of the Plague God, Sarwat Chadda sends a young Muslim New Yorker deep, deep into mythology. We’re talking Gilgamesh. I talked on Skype with Sarwat in his London home.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

In City of the Plague God, Sarwat Chadda sends a young Muslim New Yorker deep, deep into mythology. We’re talking Gilgamesh. I talked on Skype with Sarwat in his London home.

Roger Sutton: This isn’t the first time you’ve turned to mythology for inspiration. Does it ever make you nervous to be throwing what used to be a religion up in the air for your own dramatic purposes and sometimes for laughs?

Sarwat Chadda: For me, it actually goes back to “write what you love.” I want to share my enthusiasm and passion for any mythology so people will take it in a positive way. People may take it in a negative way, but that’s always going to be out of the control of any author.

Sarwat Chadda: For me, it actually goes back to “write what you love.” I want to share my enthusiasm and passion for any mythology so people will take it in a positive way. People may take it in a negative way, but that’s always going to be out of the control of any author.

RS: I wasn’t even thinking about upsetting people, except maybe the gods. You’re messing with gods here!

SC: Yeah, well, you know. That is even more beyond my control.

RS: Were these stories of Gilgamesh, Ishtar, etc., part of your childhood?

SC: Actually, it was more from my teens and twenties, when I was in London and living down the road from the British Museum. They have looted the entire world; their Mesopotamian artifacts are second to none. Because I was brought up as a Muslim, to me, when it came to stories and mythology, the big revelation was about all this other mythology that came out of the Middle East and South Asia, which I’d not really been brought up with. It felt like this massive gap in my heritage. My parents came from India, so I wanted to explore Hindu stories. And because culturally I feel a great affinity to the Middle East, I wanted to explore Middle Eastern stories that weren’t just rehashes of Sinbad and genies and flying carpets. When people talk about fantasy today, from a Western perspective, I feel like they’re actually talking about really mundane tropes. You can have dragons, elves, etc. What’s fantastical about that nowadays?

RS: Have you seen that new book, a study of the effect those Oxford guys, Tolkien, Lewis, etc., had on what we think of now as fantasy novels? [Ed. note: Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century by Maria Sachiko Cecire] As you say — dragons, elves, etc.

SC: Exactly. When I started noticing fantasy stories coming out with Middle Eastern settings, I was really excited. But then I realized every single one had got a genie in it. While I love the Arabian Nights, it felt like we were just falling into the Eastern clichés, which are different from the Western ones, but nevertheless still clichés.

RS: You’re going much further back here though, right? I don’t really understand the scale of time when it gets that long ago. “The cradle of civilization."

SC: Old school. And I had a very peripheral understanding of Mesopotamia myth. All these stories from the Old Testament and other aspects of Western civilization all came out of Mesopotamia. One of the great things about mythologies is seeing how well all the dots start connecting, and you realize, “Oh wow, that’s just that story again, but for a different people, in a different setting.” I’m a big fan of Joseph Campbell, too. Of course it goes back to Star Wars for me, how Campbell inspired George Lucas — and his idea of the monomyth. What’s great is Campbell makes you feel that all of humanity is connected. We all have exactly the same pot of stories. Being able to go back to Mesopotamia and see how much is picked up in the Old Testament was actually a really big faith revelation.

RS: Was Star Wars where your interest in the fantastic began? I don’t know how old you are…

SC: I was ten or eleven when the first Star Wars movie came out. I was part of the original audience.

RS: So was I, but I was a college student, and I was high.

SC: Like a lot of kids my age, I wasn’t aware of that much fantasy beyond things like The Hobbit and Greek mythologies. In fact, can I just show you something?

RS: Sure. [Ed. note: we’re on Skype]

SC: [Holds up New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology (1970)] My bible. I came across this in the '70s. I would memorize all the characters, all the adventures, getting really upset about the fortunes of all the Greek heroes. Mythology’s always been my first love. It feels as though it was inevitable that would feature strongly in all my writing.

RS: Despite the monomyth, what kind of differences do you find between a mythology from South Asia and one from Mesopotamia? Are there things that really tell you you’re in another part of the world?

SC: With South Asian and Mesopotamian stories, good and evil don’t exist in the way that we in the Judeo-Christian society perceive them. One of the ancient Hindu goddesses I wrote about was Kali, goddess of death and destruction. She is this terrifying demonic form with fangs, black skin; she’s got a necklace made out of skulls. Judeo-Christians believe she is the very epitome of something terrifying and evil. In Mesopotamian mythology, you have Ishtar, who’s both the goddess of love and of war. You could perceive that as she being the goddess of passion, itself neither good nor evil. In Greek myths, the heroes commit appalling acts, but they’re still heroes. I think there’s an interesting reflection here on how we perceive our heroes in the media and in culture. We might have a hero who does something admired, but then does something that we feel is actually beyond the pale. Do all the things they’ve achieved mean nothing? Are we judging them on this thing, or are we judging them overall? My daughters are insane fans of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, and the whole Johnny Depp saga is a perfect example of that.

RS: Canceled!

SC: We’re trapped in this idea that something has to be pure good or pure evil, which is a foundational structure of the Judeo-Christian belief system, which doesn’t apply to many other religions.

RS: You know, yours is the fourth book I have read now in the past five months where a kid has to go find a missing brother in another world. What is going on? What is in the water? Do you have a brother?

RS: You know, yours is the fourth book I have read now in the past five months where a kid has to go find a missing brother in another world. What is going on? What is in the water? Do you have a brother?

SC: No, I have sisters. So for me, the whole sister bond is well sorted. The most interesting thing for me was writing how a younger brother might perceive his older brother. Especially in Islam and also Southeast Asia, we are brought up to respect our older siblings. It’s kind of a default position, but, of course, there is resentment and rivalry and envy. That was fun to explore with Sik. He still has all of these negative feelings, even though his brother has passed away and has gained an even more “good” status from having died. You can’t speak ill of the dead. He feels a terrible sense of betrayal by having negative feelings toward his hero brother, whom he did incredibly look up to.

RS: Are there particular challenges in blending a contemporary kid’s world with these dark and light forces from mythology?

SC: The biggest challenge was getting the balance between the concept of there being multiple Mesopotamian gods and Sik being a devout Muslim and believing there’s only one divinity. That was the far bigger work, to make it feel that his faith wasn’t being compromised. As a Muslim and a reader of stories with Muslim protagonists, I was really sensitive about making sure I didn’t fall into the trap of suggesting that our God is like those gods. The way people saw the Mesopotamian gods is radically different from the way we perceive Jehovah or Allah — the god we worship in the here and now. That separation had to be clear and strong.

RS: It seems that monotheism may not give a fantasy writer very much to work with. If you have one god, and that god is everything, there’s not a lot of personality there.

SC: Yeah, you’ve hit the nail on the head. That was the challenge in writing City of the Plague God. I wanted to explore a Muslim kid growing up in a Western heritage, but then I wanted to have my cake and eat it, too, because nobody else has particularly written about Mesopotamian mythologies. It lined up perfectly with Sik’s Iraqi heritage. My ambitions to become a writer started about 2003 or 2004, which was the same time as the Iraq War, and a lot of my early stories were about the conflict between Islam and the West, basically stemming from my anger about what was going on. Now through Sik I could go back to that, from a generation later. What I really love about Sik is his sense of fusion, that he can be Muslim and of Iraqi descent, but still wholeheartedly American. That’s one reason I wanted to set the story in New York — you can belong in New York. I was wary of falling into the idea that there’s a constant clash of civilizations. I’ve never really felt that. I was brought up Muslim, but I was born and raised in Britain. I’ve never really felt I had to pick one or the other. Why can’t I be both? Sik was a great chance for me to write about this fusion being a wholly positive thing, rather than being a source of conflict, or some sort of internal battle the character has.

RS: One thing I like about your book is that ease that Sik has in negotiating being a Muslim, being in New York, loving his special hot sauce recipe, all that stuff that you’d think would be taken for granted, but it often doesn’t seem to be in books with religious protagonists.

SC: On the one hand, it would have been inappropriate for me to ignore Islamophobia, but I didn’t want to focus on it or get up on my soapbox: “Hey, us Muslims are good guys as well; we’ve been portrayed really badly.” Instead I just had Sik go on his adventure and show everyone he’s being heroic. But I also show, in a comic way, his cousin, a young actor, always getting typecast in auditions. When writers write about their religion, they may feel there’s a point to be proven, or have a certain sense of defensiveness. They’re reacting to outside impressions and portrayals that put their religion and things that they love in a negative light. Which is — again, I perfectly understand that. But I wanted to tread much more lightly. And at the end of the day, I wanted to write a rip-roaring adventure story. That’s my fundamental ambition. Of course, I wanted to portray a character who I really strongly relate to, so hence a Muslim immigrant. It’s those two things combined — but at the top of the page, a rip-roaring adventure.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!