Show and Tell: Curating “The ABC of It: Why Children’s Books Matter”

Not quite two years ago, The New York Public Library asked me to curate an exhibition about children’s books for its central gallery, the grand 4,500-square-foot space that lies just beyond the Library Lions (the main Fifth Avenue entrance-way) and Astor Hall.

This wall panel near the exhibition entrance features a graphic of a children's bookseller's shop from eighteenth-century London.

This wall panel near the exhibition entrance features a graphic of a children's bookseller's shop from eighteenth-century London.Not quite two years ago, The New York Public Library asked me to curate an exhibition about children’s books for its central gallery, the grand 4,500-square-foot space that lies just beyond the Library Lions (the main Fifth Avenue entrance-way) and Astor Hall. I would have a research assistant, a work area, my choice of designers, and the run of the library’s special collections. I could do more or less whatever I wished. They would pay me, too. “Yes,” I said. “I would like that very much.”

The library last mounted a major children’s literature show in the 1980s. The curator then had adopted an old-fashioned “greatest hits” approach. He had had plenty to choose from. Thanks to the library’s historic role in the development of service to children, NYPL housed one the world’s great children’s literature collections. Besides the special books, there were all the special things, gifts from artists, writers, and publishers to the Central Children’s Room and its powerful overseers: P. L. Travers’s parrot-head umbrella, the original Pooh stuffed animals, a Beatrix Potter watercolor. Other notable items were to be found in each of the labyrinthine library’s treasure rooms. The Rare Books Division possessed the oldest known copy of The New-England Primer, the most widely distributed and influential American children’s book of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Berg Collection of English and American Literature had Alice Liddell’s own copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, inscribed to her by the author. The Manuscripts and Archives Division owned Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden manuscript. The Prints and Drawings Room was home to W. W. Denslow’s original Oz illustrations as well as Arthur Rackham watercolors galore. And on and on!

Taking time out to read in the "hush" of the Great Green Room.

Taking time out to read in the "hush" of the Great Green Room.I knew, in a general way, what I hoped a new show might accomplish. A great many people form strong, even passionate personal associations with children’s books — connections forged in childhood or later in life — but without seeing those books in broader cultural terms, as literature and art. My goal would be to present children’s books in that larger context, to connect the dots by highlighting the place of children’s literature, broadly defined, in the arts, popular culture, and social history.

First came a whirlwind round of meetings with collection curators. List-making was a big part of this exploratory phase: lists of things I had seen and then, as my focus sharpened, lists of things needed to round out this or that story. I knew, for instance, of many picture book artists who had also made fine-art prints, posters, or drawings at one time or another (Vladimir Lebedev, Wanda Gág, Bruno Munari, Jean Charlot, Don Freeman) and of fine artists who had occasionally made picture books (El Lissitzky, Kurt Schwitters, Faith Ringgold). Displaying the various facets of these artists’ work side-by-side was one way to showcase the art-worthiness of children’s book illustration. Not every search for material paid off, but it soon was white-gloves-and-pencils-only time as the Print Room staff hauled out the first of many oversized archival boxes of art from around the world for me to examine.

Nathaniel Hawthorne as parent, fantasist for children, and — as the author of The Scarlet Letter — Romantic champion childhood.

Nathaniel Hawthorne as parent, fantasist for children, and — as the author of The Scarlet Letter — Romantic champion childhood.Excavating the Berg Collection catalog was another jaw-dropping experience. The Lewis Carroll holdings alone were staggering: multiple special copies of Carroll’s famous books, significant caches of letters and photographs, a set of original John Tenniel drawings. The Hawthorne archive drew my attention early on, too. I knew going in that Nathaniel Hawthorne not only had published storybooks for children under his own name but that as a young unknown fiction writer he had supported himself in part as a ghostwriter for Samuel Goodrich, the energetic nineteenth-century Boston juvenile author/entrepreneur who won fame and fortune as Peter Parley. Now I discovered that, during his dry spell just prior to writing The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne had kept a journal of his young children’s activities. Hawthorne the family man! He doted on his daughter and son and rejected the New-England Primer on which his stern colonial-era Salem ancestors had been reared. By the time I came across the Hawthorne household’s Mother Goose collection at Berg, with certain rhymes marked “Not to be read to Una” by the children’s protective mother, Sophia, it was clear there was a compelling story to tell about an American Romantic known to most of us only as high-school required reading.

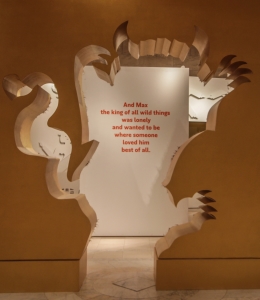

This Wild Things cutout serves as a gateway to a consideration of Romanticism in children's books, from the Grimms and Andersen to Sendak, Zwerger, and beyond.

This Wild Things cutout serves as a gateway to a consideration of Romanticism in children's books, from the Grimms and Andersen to Sendak, Zwerger, and beyond.Still in need of an overall plan for contextualizing these and many other remarkable finds, I next made lists of key questions around which the show might be framed. How, for instance, had changing ideas about childhood led to the different kinds of children’s books that have come down to us? The exhibition opens with the suggestion that behind every children’s book there lies a “vision” of childhood: the Puritan vision of original sin as exemplified by the fire-and-brimstone New-England Primer; the Enlightenment vision codified by John Locke and played out in the pointedly entertaining illustrated books introduced by John Newbery; the Romantic vision that inspired excursions into fantasy by Hawthorne, Hans Christian Andersen, and later E. B. White and Maurice Sendak; the progressive educators’ vision of the self-directed, collaborative child that found sly expression in experimental picture books like Goodnight Moon and Harold and the Purple Crayon. The Hawthornes’ Mother Goose volume inspired a sidebar to the display cases devoted to the Romantic Child. “At Home with the Hawthornes” considers not only the writer’s contributions to literature but also the impact his experiences as a parent had on his work — most notably as the father of Una, his model for The Scarlet Letter’s Pearl. This first, and largest, of the three major sections of the exhibition also looks at the “citizen child”: the role of children’s books as tools for building national identity, with examples gathered from post–Revolutionary War America, Bolshevik Russia, 1920s Palestine, post-colonial India, Mao-era China, and contemporary Francophone Africa, among other places.

Alice grows up — and down — alongside a set of drawings by Sir John Tenniel.

Alice grows up — and down — alongside a set of drawings by Sir John Tenniel.The other question explored in this first major section is: how have children acquired their books? The show concentrates on three ways: as gifts, at the library, and in secret. A focus on gift books became an opportunity to sketch the rise of the commercial trade in children’s books, not only in the West but also in Edo-era Japan, and to display deluxe gift editions illustrated by Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Ivan Bilibin, and others. Children’s magazines such as St. Nicholas and the less-well-known Brownies’ Book, which was launched in the early 1920s by NAACP founder W.E.B. Du Bois, were another kind of gift. So too were homemade books that became famous when published: Alice, Pooh, and Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense, the latter represented by a rare hand-drawn copy. The Poky Little Puppy takes its place in this section of the exhibition as well, as a landmark in the democratization of publishing for children: at last, a gift book nearly every parent could afford.

The exhibit cases devoted to children as library goers spotlight the activist role of early-twentieth-century American librarians in establishing free access to books. New York Public’s Anne Carroll Moore is profiled, as are two librarian pioneers of multiculturalism, Augusta Baker and Puerto Rican–born Pura Belpré, whose hand puppets are on view. The “secret readers” case features comic books and traces the bitter debate their immense popularity sparked among librarians, psychologists, and other experts who could not fathom their value or appeal.

The exhibition continues in two more major sections. The first of these zooms in closely on the picture book. It invites visitors to reappraise the artistry that lies behind these supposedly simplest of all books. It pinpoints the modern picture book’s origins in the dynamic graphic experiments of Randolph Caldecott. And it posits the picture book as the laboratory in which the future of the printed book will be decided.

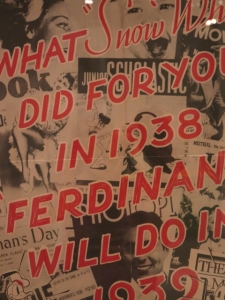

The Story of Ferdinand as a Hollywood sensation and marketing bonanza generated by Walt Disney.

The Story of Ferdinand as a Hollywood sensation and marketing bonanza generated by Walt Disney.The third and final section of the exhibit illustrates a variety of ways in which children’s books have had an impact on the larger culture. Books that have inspired films, plays, and fashions, or have otherwise become cultural phenomena, are displayed alongside relevant artifacts and memorabilia: film stills, pop chart recordings, and licensed products spun off from Mary Poppins and The Story of Ferdinand; a sampling of the frenzied media coverage generated by Harry Potter. We track one nursery rhyme, “Humpty Dumpty,” as it threads its way through the work of Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, Charles Addams, Robert Penn Warren, Aretha Franklin, and Woodward and Bernstein. And we highlight books — from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Wrinkle in Time to The Diary of a Young Girl, Pippi Longstocking, and The Beast of Monsieur Racine — which, having touched a cultural nerve, went on to incur the wrath of censors. Visitors are sent on their way via a selection of books with New York settings and themes: stories inspired by the storied city which, not coincidentally, has long been one of the world’s capital cities of children’s book publishing.

I write this column two weeks before “The ABC of It” opens to the public. It is impossible to know just who will see the show, but in all likelihood upwards of a quarter of a million people will do so: admission to the gallery is free, and the library itself is one of New York City’s most popular tourist destinations. The exhibition will remain on view for nine months. The only assumption to be safely made is that many of those who view the show will arrive with a favorite children’s book in mind, looking perhaps to encounter it again in the gallery. I hope visitors will leave thinking about that book, and all the other books in the exhibition, in surprising new ways: as tales belonging to certain vital storytelling traditions; as works of art crafted by flesh-and-blood artists and writers; and as the messages in the bottle that each generation sends out to the next, because it wants its hopes and dreams to last.

The ABC of It: Why Children’s Books Matter

curated by Leonard S. Marcus

The New York Public Library,

Stephen A. Schwarzman Building,

Gottesman Exhibition Hall

Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street

New York, New York

Friday, June 21, 2013–Sunday, March 23, 2014

All photos courtesy of the New York Public Library. From the September/October 2013 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

porrer

Check this out https://www.arts.gov/art-works/2014/why-childrens-books-matterPosted : Feb 28, 2016 05:37

Darla Grediagin

I was able to see “The ABC of It” while in New York City last month. Neither my husband or I knew about this before our visit. It was a very pleasant surprise to find it at the library. As a school librarian, I was able to learn a lot that I can take back to my student's on the west coast of Alaska.Posted : Dec 06, 2013 02:50