Phoebe Wahl’s The Blue House feels like it’s been around for a long, long time — while also being utterly groundbreaking.

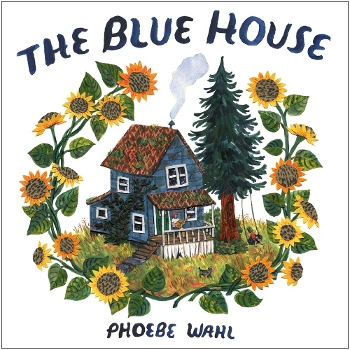

Caldecott terms and criteria stipulate that the Medal goes to a picture book published “during the preceding year.” Although the 2020 publication of Phoebe Wahl’s The Blue House satisfies this term, it feels like it’s been around for a long, long time — while also being utterly groundbreaking. Picture books abound about houses and homes, about loss and moving on, and about parent-child bonds; but very few offer stories of single-father households, of families who rent — rather than own — their homes, or of the impact of gentrification on the poor and working class. The Blue House is “individually distinct,” as it does all of this — and more.

Caldecott terms and criteria stipulate that the Medal goes to a picture book published “during the preceding year.” Although the 2020 publication of Phoebe Wahl’s The Blue House satisfies this term, it feels like it’s been around for a long, long time — while also being utterly groundbreaking. Picture books abound about houses and homes, about loss and moving on, and about parent-child bonds; but very few offer stories of single-father households, of families who rent — rather than own — their homes, or of the impact of gentrification on the poor and working class. The Blue House is “individually distinct,” as it does all of this — and more.

When talking Caldecott, it’s natural to connect this picture book and Virginia Lee Burton’s 1943 Caldecott Medalist, The Little House. Thematically, both titles focus on a (little) house, after all, and the artists share common ground stylistically, with surfeits of rounded forms, curved lines, and the clear influence of their common experience in textile design. But their differing story structures and resolutions highlight how Wahl’s book, while familiar, is something new: where Burton offers readers a nostalgic, happily-ever-after ending that rescues the Little House from the city that’s grown up around her and restores her to a rural, bucolic setting, Wahl acknowledges the love at the heart of sentimentality without succumbing to its limiting pitfalls. By not rescuing the Blue House from gentrification and the developer’s wrecking ball, and by showing how human characters endure loss and start anew, Wahl’s story resists the pull of nostalgia and looks ahead to the future.

Furthermore, even though the Blue House is eponymous, this isn’t “Her Story” (to borrow The Little House’s subtitle). Instead, Wahl centers young Leo as the protagonist and visually signals his importance — not on the cover, where his tiny form is barely visible on a tire swing suspended from a fir tree, but on the title page. Here, we see another depiction of the Blue House, this time rendered in a naïve style as though painted by a child’s hand — Leo’s hand. The sun shines brightly in this picture, and giant flowers stand in cheerful companionability with the fir tree. This is a happy picture, made by a happy child, and this book is about his sense of home.

Wahl excels in her “delineation of…characters” with her depiction of artistic Leo, who emerges as a specific individual in her careful creation. He resists gender norms, with long, brown hair, a penchant for pink socks, and a tender heart that exhibits itself in scene after scene. It’s immediately apparent that Leo’s happiness and individuality is nurtured by his devoted father, to whose portrayal Wahl devotes equal care. He’s made the Blue House a cozy home for himself, his son, and their cat, one in which they dance, bake pies, build blanket forts, draw, read, garden, and make music. Only passing mention is made of Leo’s schooling, and there’s no indication of employment for his dad. One gets the sense that gardening isn’t a hobby so much as a means of sustenance, and that he ekes out a living, perhaps as a musician, or with some other creative pursuit. Details in the setting help construct this understanding of Leo’s father, including playful use of text on books and record albums in the illustrations that mark him as a vinyl connoisseur and avid reader. Underneath the jacket, these record albums, books, and other belongings decorate the printed case, inviting readers to play an I-spy game in the pages to find these beloved objects in the Blue House — and, crucially, later in their new house.

While these items and other elements of the setting help construct character, they also infuse the Blue House itself with a sense of hygge, despite its dilapidation. The walls of the home are dingy, but they’re decorated with art (by Leo and others), and plants and fabrics add visual texture. Earth tones and the rounded forms and curved lines that recall Burton’s work proliferate. “But it was theirs” reads an early line of text after Wahl details the “leaks and creaks” and other signs of wear the Blue House displays, conveying a sense of home ownership present in the characters’ hearts, if not in their status as renters.

Their tenancy makes them vulnerable to the landlord’s power to sell the Blue House. This heart-wrenching turn of events is anticipated in the front endpapers, where an aerial view of a neighborhood shows it standing among several other run-down houses, some with "For Sale" signs. This is a neighborhood in transition, a state made clear when the text explains how “there was all kinds of construction going on in the neighborhood.”

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of The Blue House here]

When Leo’s dad must share that the landlord is selling the Blue House, he brings Leo to the beach, where they sit eating ice cream in a driftwood structure. It’s reminiscent of a blanket fort they made earlier and functions not just as an interesting visual element of the composition but as a meaningful symbol of home during this moment of anticipatory loss. This setting detail, unmentioned in the text, serves as just one powerful instance where Wahl demonstrates “excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept”; the father, who can’t protect his son from the loss of their home, quite literally shelters him while breaking the bad news. Ensuing pages demonstrate Wahl’s investment in visually interpreting home as a theme. Leo barricades himself in his room after hearing the news, and art shows his dad worriedly standing outside his door, while Leo drapes himself with a blanket, an abandoned Lego-like structure on the floor, and that same picture of the Blue House from the title page hanging on his wall.

Wahl’s introduction of the new home for Leo and his dad happens well before they move in, in the lower-right corner of the front endpapers. Here, a little white house stands in the shadow of an apartment building, a “For Rent” sign in its yard. Though he’s at least gets to stay in the same neighborhood, Leo’s grief on their first night in this new house is palpable as he says, “‘I hate it,’” while cradled in his father’s arms. The page in this scene is expressively stark and gray, but his father’s embrace and his response — "That’s okay” — is warm as ever.

Efforts to make this new house feel like a home, and to carry on the memory of the Blue House, are symbolically reinforced by Wahl’s closing endpapers, where the new house stands with sunflowers growing in front and a tire swing appears on the branches of a tree in its yard. The tire swing was clearly moved from the fir tree at the Blue House, but the sunflowers are something new. They weren’t present on the front endpapers; they’re a new addition to a new home, symbolizing the growth and renewal that defines this plot. Noticing the sunflowers on the back endpapers casts the picture on the cover in a new light: as a memory. Leo and his dad will always remember the Blue House, but they’re not stuck in the past. They are moving forward, together.

This is a picture book that rewards repeat readings and will doubtlessly stay in readers’ memories. It’s a timely book in a moment where economic insecurity impacts the lives of so many children and their families, and in its “conspicuous excellence or eminence,” it strikes me as timeless, too.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!