Less a story than a book about an idea, the central message of Corinna Luyken’s debut, The Book of Mistakes, appears as paratextual coda on the back of the jacket: “Set your imagination free.

Less a story than a book about an idea, the central message of Corinna Luyken’s debut, The Book of Mistakes, appears as paratextual coda on the back of the jacket: “Set your imagination free.” According to Caldecott criteria, the Caldecott is "not for didactic intent,” but Luyken delivers her message as a masterful celebration of creativity rather than a lesson. Its central premise — that “mistakes” are opportunities for inspiration — never feels heavy-handed. Instead, inventive, engaging, metafictive text and illustration fulfill the criterion of “excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience,” while positioning the book as a resource for adults keen on encouraging kids to, in the words of Ms. Frizzle, “take chances, make mistakes, get messy!” Taking a chance myself, I’ll say it’d be a mistake for the 2018 Caldecott Committee to overlook this stunning, playful picture book.

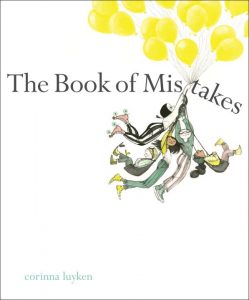

Less a story than a book about an idea, the central message of Corinna Luyken’s debut, The Book of Mistakes, appears as paratextual coda on the back of the jacket: “Set your imagination free.” According to Caldecott criteria, the Caldecott is "not for didactic intent,” but Luyken delivers her message as a masterful celebration of creativity rather than a lesson. Its central premise — that “mistakes” are opportunities for inspiration — never feels heavy-handed. Instead, inventive, engaging, metafictive text and illustration fulfill the criterion of “excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience,” while positioning the book as a resource for adults keen on encouraging kids to, in the words of Ms. Frizzle, “take chances, make mistakes, get messy!” Taking a chance myself, I’ll say it’d be a mistake for the 2018 Caldecott Committee to overlook this stunning, playful picture book.The portrait layout’s generous trim size makes immediate visual impact with striking jacket art that depicts children grasping a bunch of balloons lifting them into empty, white space. The fearlessness of this open background acts as precursor to nearly empty opening pages, which gradually give way to increasingly complex compositions. But before heading into the book proper, there’s more to consider about layout, jacket, and case design. First, look at the low, small depiction of a boy on the back of the jacket looking up at the floating children.

Is this a “mistake”? Was he left behind?

Acknowledging the plural titular noun, “Mistakes,” and examining display type, look, too, at how the floating children and balloons disrupt the title.

Another “mistake”?

Remove the jacket to examine the case, which omits words and provides more detail for the left-behind boy: his now-visible unicycle is outfitted with a big balloon.

Will he pedal forth and soar into the sky after the others?

The stage now set to test theories about the narrative, open the book to pause at the endpapers, which are expanses of white marred by two black inkblots.

Even more “mistakes”?

Perhaps. But their placement seems deliberate, since they’re positioned in the same places as the floating children and the boy. This minimal, intentional design introduces the inkblot motif found on future pages, and their positions anticipate how interior compositions exploit the portrait layout by reaching for upper and lower heights to emphasize space, movement, and perspective — elements key to the ensuing, complex visual narrative.

Turn to the dedication page, and you’ll find a small animal (later called “the frog-cat-cow thing”) and another inkblot on the title page — right on the i in “Mistakes.” These details prompt readers to expect them on subsequent pages, just as jacket art introduced human characters who will reappear. The first such character shows up in the opening spread as a tiny, incomplete sketch of a face with one eye, one ear, a nose, and a mere suggestion of an eyebrow. “It started,” reads spare, accompanying text, and a page-turn completes the sentence: “with one mistake.” Now the face has a line for a mouth, penciled-in hair, another tiny eyebrow, and a big, black circle of an eye, far larger than the first, small eye. That text doesn’t specify this outsized second eye as the “one mistake” allows readers to name it themselves. Luyken trusts readers to fill in gaps and comprehend how words and pictures work together, a responsibility that reinforces the trust she places in the creative process by positioning reading as a creative act aimed at making meaning. In a picture as simple as this one, it’s an easy task that prepares readers for ever closer examination of ensuing spreads.

In these early pages, Luyken transforms the eyes into glasses, establishing a pattern of “mistakes” providing creative inspiration. She thus presents art-making as a kind of problem-solving. This doesn’t come across as a slog, but as a process that demands a playful mindset undeterred and, indeed, fed by mistakes. The apparent pleasure Luyken takes in her process translates into pleasurable engagement for readers, as pages with “mistakes” like “the elbow and the extra-long neck” provoke laughter at how she plays with rules of proportion. Clearly, she’s an artist who knows the rules and can therefore break them for humorous effect.

But there’s more than humor here; paratextual promises are kept, too. The evolving drawing of the bespectacled face emerges as a quirky roller-skating girl, recognizable as one of the floating children from front jacket art. This connection provokes wondering about the balloons and when they and the other children will reappear. Luyken soon delivers and fills subsequent pictures with those details observed early on. The result is bookish wish-fulfillment — we get what we expect, and we get much more, too. The balloons? They’re delivered by the roller-skating girl in wordless spreads that invite readers to narrate her progress toward a massive tree. The other children? They’re cavorting among the tree’s branches.

Play with visual perspective then seizes control to make setting become character and (perhaps) character, self-portrait. A textual shift to the second person implicates the reader in the metafictive results: “Do you see—” it asks as shadows creep in inky darkness on the lower part of the spread. A page-turn zooms out much farther, with blackness dominating the verso, while the scene of the roller-skating girl approaching the tree with the balloons becomes ever smaller, but remains recognizable, in the lower recto.

Delighted interjections abound at storytime when the shadowy landscape transforms into the huge, helmeted head of the roller-skating girl, with the tree scene sprouting from the top of her head. Then, perspective zooms out to cast her not just as a skater, but an artist drawing the same, slight sketches that opened the book, and positioning her as a sort of self-portrait of the artist as a young girl. As one child at storytime remarked, “Since the girl in the book is the one making the pictures of herself, it’s like she’s the real artist. We’re seeing how the real artist thinks.”

It’s extremely satisfying that something so unexpected culminates a book whose paratexts initially guide readers to search for and find the expected, and this child’s comment seems an ideal articulation of what this picture book does so well: it captures Luyken’s imaginative, creative process in order to “set … free” readers’ imaginations. The playfulness of her words and pictures as she achieves this paradoxical feat exemplifies the Caldecott criterion of “excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept,” leading me to conclude that there can be no mistake about it: this is a picture book worthy of Caldecott recognition.

Read the Horn Book Guide review of The Book of Mistakes.

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Emmie

Megan, haha I love that Mistakes reminded you of Go Dog Go too! I really enjoyed reading the rest of your intertextual notes. I can see how pushing aside intertextual connections would be really hard when serving on the Caldecott committee. Your connection with Spring is Here is brilliant. The 'character-to-setting-to-character' aspect of Mistakes is very well done -an element I missed on the first couple of readings. I can't wait to see if my students notice it. I'd love to read others' thoughts on your question regarding a committee referencing previously published books. When books win awards it seems like they're inevitably compared to other books.Posted : Oct 18, 2017 07:23

Sam Juliano

Congratualtions on your new baby!!!! Best Wishes!!!!! :)Posted : Oct 15, 2017 09:40

Megan Dowd Lambert

Emmie, You read my mind with the Eastman connection! Here's some content on intertextual connections that I had to cut from my first draft of this post: "Although stylistically quite different, I can’t help but think of P.D. Eastman’s outrageous dog party in the tree at the end of Go, Dog. Go! when I see the first, whimsical spread depicting Luyken’s tree with the children climbing all over it. And I thought of one of her artistic contemporaries, Erin E. Stead (and especially her book with Julie Fogliano, And Then It’s Spring), when I first saw this picture, too, because her palette and style have a similar, vintage feel that embraces white space, relishes flat patches of darkness for the tree’s massive trunk and branches, and achieves clean, compositional balance with careful arrangement of soft colors. No, the real committee isn’t charged with making such intertextual connections, but when Calling Caldecott I can’t help but think that such readings enrich one’s experience of a picture book, whether the artist intends the references or not. As the visual perspective zooms outward in a series of spreads building toward the book’s metafictive ending, Stead’s work in And Then It’s Spring recedes from my mind, and I instead recall Spring Is Here by Japanese artist, Taro Gomi. In Gomi’s book, what we initially regard as a character (a calf) turns out to be a setting, which then shifts again back to character. In The Book of Mistakes, what we regard as setting (the shadows and trees) turns out to be a character." I served on the 2011 Caldecott Committee, and pushing aside intertextual connections was a huge challenge for me when writing nominations and discussing books. Confidentiality rules prevent me from saying much more about that experience, but I will say that I learned a lot about myself as a reader who builds meaning in one book by thinking about its connections with other books. It's difficult, to say the least, for me to read books in calendar-year isolation. What do others of you think about the term "The committee in its deliberations is to consider only books eligible for the award, as specified in the terms." I understand the limitation of considering books for the Medal and Honor(s) from a given year, but do you see wiggle room for referencing other books from other years in one's consideration? Or is this absolutely a violation of terms?Posted : Oct 15, 2017 02:22

Megan Dowd Lambert

Thanks for the comments, everyone. This post went up on the very day I had my new baby, so I wasn't able to respond right away but am eager to do so now. Kazia, I had a really powerful emotional response to this picture book, too. I think it's more common for picture books to move us through characterization, but this one is powerful because of how it speaks, not through character, but through reader response to message and theme. The former kind of impact relies on a mimetic reading that regards characters as real, or authentic, or believable. The latter instead asks readers to reflect on the characters and other elements of the book as the products of a creative mind. This creates great potential for a sense of communion with the artist, a marvelling at the mind behind the creation. And, it in turn provokes awareness of one's own reading mind as contributing to the creation of story. I call my blog "Book Happenings" after a favorite quotation from Reader Response theorist Louise Rosenblatt: "Books do not simply happen to people. People also happen to books." I think that the emotional power of this book is how very much it relies on and overtly revels in people happening to books. In fact, my first draft of this post was about twice as long as the published one (Jules and Lolly were very patient editors) and it included additional content about my daughter's reading of this book. I cut it but just may resubmit it for the Family Reading blog...Posted : Oct 15, 2017 02:09

Emmie

Megan, reading your post caused me to immediately pull out my copy of Mistakes so that I could notice all of the details you discussed. Your observation, "Luyken trusts readers to fill in gaps and comprehend how words and pictures work together, a responsibility that reinforces the trust she places in the creative process by positioning reading as a creative act aimed at making meaning." is a aspect that had not occurred me. Luyken achieves the reader responsibility concept (which sounds simple, but is hard to execute) with grace. The Book of Mistakes was an instant favorite with my students sparking much conversation. Pairing 'The Book of Mistakes' with Santat's 'After the Fall' lets students discuss different aspects of the growth mindset concept. One personal and somewhat random observation...the illustration with the tree on the girl's helmet reminds me of the last illustration (its a dog party!) in P.D. Eastman's 'Go Dog Go'.Posted : Oct 14, 2017 09:29