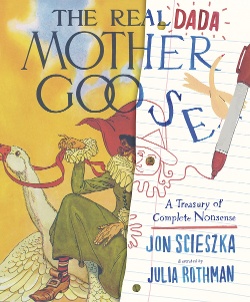

The absurdist The Real Dada Mother Goose, illustrated by Julia Rothman and written by Jon Scieszka, (unsurprisingly) upends conventions — and because of its use of Blanche Fisher Wright’s original illustrations also raises provocative questions about its Caldecott eligibility.

[Many Calling Caldecott posts this season will begin with the Horn Book Magazine review of the featured book, followed by the post's author's critique.]

The Real Dada Mother Goose: A Treasury of Complete Nonsense

The Real Dada Mother Goose: A Treasury of Complete Nonsense

by Jon Scieszka; illus. by Julia Rothman

Primary, Intermediate Candlewick 80 pp. g

10/22 978-0-7636-9434-0 $19.99

Since the 1992 publication of The Stinky Cheese Man (rev. 11/92), Scieszka has been upending conventions in children’s literature. Here, he’s back at it, with a Dadaist interpretation of Blanche Fisher Wright’s classic The Real Mother Goose. Scieszka focuses on four Mother Goose rhymes plus “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” modifying each entry multiple times and creating absurdist variations. For example, he rewrites “Jack Be Nimble” backwards, in pig Latin, and in Esperanto; as Mad Libs–like fill-ins; as a multiple-choice quiz; and as a child’s book report. Language-play abounds, including translations into Morse code; verbal and nominal substitutions; spoonerisms; and “Jabberwocky” (“Old Mother Jabbber went to the clabber, / to get her frum jub a gove”). Encouraging youngsters to create their own riffs on literature, Scieszka includes explanations of many of these linguistic conventions. Rothman illustrates each poem by altering Wright’s original illustrations—superimposing her own mixed-media collages on some, clipping others and rearranging the parts, adding geese to populate many pages. Clever, inventive fun. BETTY CARTER

From the November/December 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

As Calling Caldecott's mock vote nears and in anticipation of the ALA Youth Media Awards on January 30, we take a moment to reflect on the eligibility rules for the Caldecott Medal. As the picture book course at Simmons University prepared for its mock Caldecott, students wondered about the eligibility of Julia Rothman’s The Real Dada Mother Goose: A Treasury of Complete Nonsense, written by Jon Scieszka. Cathie Mercier (director of the graduate programs in children’s literature at Simmons University), Vicky Smith (access services director, Portland (Maine) Public Library), and Shelley Isaacson (picture book course instructor) share their unfolding discussion about the book's eligibility.

CATHIE MERCIER: Near the end of last semester, I was hanging out in the BookNook at the Center for the Study of Children’s Literature when one student asked, “Professor Mercier, how would your Caldecott committees have handled the question of eligibility about The Real Dada Mother Goose?” I took a quick look at the book to offer a limited answer: I questioned its eligibility. I also noted that this is a question the committee might want to consult with their Priority Group Consultant (PGC), a member of the Association of Library Service to Children (ALSC) detailed to help the organization’s committees with their work.

SHELLEY ISAACSON: Students write three nomination papers as their culminating assignment in the picture book class at the Center for the Study of Children's Literature. A passionate advocate for the book wondered if the Caldecott manual’s guidelines about “original art” would make the book ineligible. Should I keep the book on our class list? I reached out to Cathie, who sent me to Vicky Smith, a former ALSC board member and 2010 Sibert committee chair.

VICKY SMITH: Here's how this sort of question would play out in a real Caldecott committee:

The chair's role is not to make qualitative rulings beyond determining the most concrete basics: the book is published for children in the U.S. during the year of consideration, and the creators are U.S. citizens or residents. The chair might run it past their PGC if they have any qualms that extend beyond those very simple yes/no questions. I would personally not have had any qualms, but it's possible a committee member might have brought a concern regarding the proportion of old art to new. If they had, I would have consulted with the PGC. The PGC looks at the book and the Caldecott award manual to consider whether the book meets the criteria.

Here’s the exact wording of the manual with regard to “original work”:

• "Original work" means that the illustrations were created by this artist and no one else.

• Further, "original work" means that the illustrations are presented here for the first time and have not been previously published elsewhere in this or any other form. Illustrations reprinted or compiled from other sources are not eligible.

On the face of it, Wright’s original illustrations are all over The Real Dada Mother Goose, and they have certainly been previously published. However, she is not the illustrator of record of The Real Dada Mother Goose. From a legal standpoint, Wright’s 1916 illustrations are in the public domain (as are the rhymes that form the foundation of the text), and from a procedural one, she’s not in the Caldecott running.

When I looked at the book, I considered how the new illustrations interact with the old ones, and it seems very clear to me that in the context of the book, the new illustrations are engaging with the old ones in a playful, transformative way. The illustrations expand on both the written text and the inherited illustrative text to create a synergy that is greater than the sum of its parts. And isn’t that what picture books are supposed to do?

CATHIE: In reading this part of Vicky’s response, I immediately realized what I should have said to students and how I should have drawn on my own experience as a Caldecott committee member (1994: Grandfather’s Journey; 2012: A Ball for Daisy). What I should have done was shared an example. Perhaps Me...Jane, a 2012 Caldecott Honor by Patrick McDonnell in which the artist uses an iconic photograph of Jane Goodall and one of her chimpanzee subjects as part of his illustration. How might this use fit into an understanding of original art?

To answer Vicky’s question about what picture books are supposed to do, we need to ask how illustrator Rothman was using Wright’s work. How does this picture book combine art and text? How do art and text interact and what do they achieve? How did this book differ or cover similar territory of other books under consideration for 2022? Does it make a unique contribution?

SHELLEY: Does “original art” simply mean art created for this book that has not been previously published, or can it mean art that visually quotes other art? For example, doesn’t David Wiesner visually quote L. Leslie Brooke in The Three Pigs? Is there a line between original art and visual quotation?

CATHIE: Rothman does something quite different than does Wiesner. Wiesner draws his version of Brooke’s art; he put it in his own hand. Rothman scanned Wright’s images. Thus, the 2022 illustrations use the originals to achieve different narrative ambitions.

VICKY: In my understanding of the criteria’s intent, ALSC’s requirement that reprinted material does not constitute more than a certain proportion of the totality is to ensure that the book under consideration now has not been seen prior to this year. Rothman’s 2022 spin on the 1916 original art has distinct aspirations and accomplishments. The “Humpty-Dumpty” illustration that appears with the original rhyme is as Wright painted it, with the anthropomorphic egg just beginning its tumble — but with the turn of the page, the text presents a “Censored” version, complete with blacked-out words. Rothman’s painted goose, executed in loose, unconfined strokes that contrast effectively with Wright’s precisely outlined watercolors, now holds a can of black paint and stands next to Humpty on the wall. Humpty is in exactly the same state of imbalance as in the original illustration, but now the birds and birdhouse in the background are blotted out with strokes of black paint. Why did the goose single the birds out? Who knows? The question is the point. In another version of the same rhyme, which presents Humpty’s “Postcard” home from summer camp, only those “censored” elements remain from the original illustration, the birdhouse as the postcard stamp and the birds in the background behind the hand-lettered postcard, possibly indicating the front of the next postcard in the stack; Rothman’s goose now appears as a letter carrier standing atop it. The original illustrations are thus incorporated into Rothman’s in a way the 1916 book’s readers never saw them.

I say keep it on the picture book class list and let the book's champion(s) articulate why they feel the presentation in The Real Dada Mother Goose and its use of archival material make it the most distinguished picture book of the year. If I were facilitating, I would ask opponents who simply look at the raw proportion of old to new to listen hard to the champions' arguments.

SHELLEY: When Vicky, our stand-in PGC, chimed in with “I say keep it on the list,” I was delighted. I let the student champions for the book speak in their written nominations. I was again delighted when those written nominations successfully got “deeply into understanding and evaluating the book’s ambitions” (to quote Cathie). A win indeed.

CATHIE: This Mother Goose re-imagines the whole production through a Dadaist lens. More than the “re-telling, re-illustrating and re-mixing” promised in the creators’ notes, it disrupts traditional logic and reason. It uses Wright ”as archival material” (to quote Vicky) and disorders the formal composition of the art to unsettle any stability that the art and the rhymes themselves might have had. I agree with the flap copy that the book "deconstructs," an oft-misused word. The art and text — and even our discussion of eligibility — tease the whole question of origin and original and puts it all back together into a different thematic whole that celebrates absurdity. Absurdity becomes a new thematic unity — deconstruction in the most literal sense because it un-does and re-does differently. That the text’s back matter notes the sketchy unknown origins of Mother Goose further underscores the absurdity of the new project.

Although we can’t offer a final decision on eligibility or a final definition of “original art,” our conversation about these questions did yield new appreciation for The Real Dada Mother Goose. And isn’t that what Calling Caldecott is meant to do?

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!