Which discussion-provoking Caldecott-related issue will guest posters Elisa Gall and Jonathan Hunt tackle this time? Oooh — this year it's the part of fthe Caldecott criteria specifying that the award is not for "didactic intent."

ELISA GALL: Part of the Caldecott terms and criteria reads: "The committee should keep in mind that the award is for distinguished illustrations in a picture book and for excellence of pictorial presentation for children. The award is not for didactic intent or for popularity."

ELISA GALL: Part of the Caldecott terms and criteria reads: "The committee should keep in mind that the award is for distinguished illustrations in a picture book and for excellence of pictorial presentation for children. The award is not for didactic intent or for popularity."

In recent years, I've seen more and more books getting published (and heavily promoted) that don't shy away from being explicit: they own their messages outright. Have you noticed this?

JONATHAN HUNT: There is an abundance of books published this year that I would describe as affirmations of identity and self-worth, books like All Because You Matter; Black Is a Rainbow Color; Child of the Universe; You Matter; and Magnificent Homespun Brown. Three of these five illustrators—Bryan Collier, Ekua Holmes, and Christian Robinson—already have Caldecott pedigrees, and a fourth, Raul Colón, has had a similarly distinguished career. The caliber of these artists commands attention, and I can certainly make a case in their books for excellence of pictorial presentation for children. Each book also has an explicit message that some people may find didactic. But this begs the question: didactic for whom? To what extent does this kind of an argument provide cover for white fragility?

ELISA: "For whom?" Exactly! Children's books are always playing a role in the socialization of young people, and every book has a message. Is the message subtle? Subtle for whom? Is it heavy-handed? For whom? Is it popular? For whom?

Affirmations of racial identity and self-worth get seen as didactic to some librarians, but which affirmations are regarded as "normal," and which affirmations are regarded as didactic — and to which librarians? I think we’re saying this, but just to be explicit: it's the white kids and librarians (and those with other majority culture identities and experiences) who usually get centered. White supremacy culture shows up in the children's literature world too. The two of us are white. So much of what the two of us have been trained to regard as apolitical or "not didactic" is media, norms, etc. that center our own comfort, experiences, and the messages of superiority we have internalized as white people — often subconsciously.

K.T. Horning wrote about didacticism and the Caldecott criteria in the Horn Book several years ago, stating:

Within the children’s literature field, we talk a lot about the fact that the Caldecott Award is not for popularity. We talk less often about didactic intent. Perhaps this is because children’s book critics are so leery of anything that smacks of didacticism. No one wants to be preached at through art, we argue, especially not children.

And yet we preach to children all the time through their books. We preach that they should share with others. We preach that they should be proud to be individuals. We preach that they should not be bullies. We preach that they should learn to be independent. We preach that they should be really, really sleepy at bedtime.

When I was in library school, I was taught (pretty overtly, unfortunately) that popular and message-driven books are not to be respected as quality literature — but, of course, this is just plain wrong. There are both great and terrible books that are popular, and the same with books with perceived didacticism. While the award is not for popularity or didactic intent alone, that does not mean a book cannot be both didactic and be the most distinguished picture book of the year!

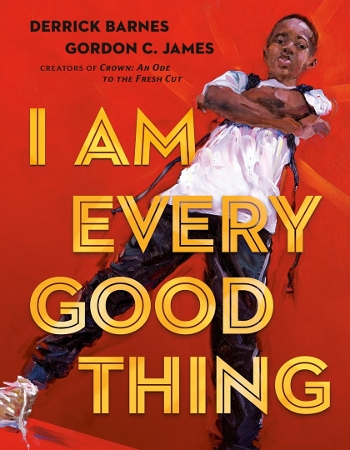

Speaking of amazing books, have you seen I Am Every Good Thing? This is another one that I would put in the category of affirming/potentially regarded as didactic to some people, and Gordon C. James's oil paintings are so vibrant, full of life, and representative of the theme that I would be nominating it for sure if I were sitting on this year’s Caldecott committee.

JONATHAN: Ack! How could I forget I Am Every Good Thing? It's arguably the best of this bunch — and recently won the Kirkus Prize.

I’ve been doing lots of professional reading about ethnic studies, social justice, and equity, and it all talks about the importance of developing a positive sense of identity, including self-worth. The best book, Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy, by Dr. Gholdy Muhammad, advocates for developing identity, skills, intellect, and critical thinking about who holds power.

All of this reading has helped me understand that if I might have been underwhelmed by or unappreciative of affirmation books in the past, then perhaps it was because our culture, media, and society constantly send me messages of affirmation. And a reader who does not get these messages would have different reading needs than mine.

I am curious: do you think any of these affirmation books would be knocked out of contention solely because of didactic intent — or the perception thereof?

ELISA: Obviously, this depends on the committee and their perceptions. One critique I've heard about recently published books with unapologetic messaging is that they might be beautiful, but they don't have a compelling story. This is where I might push back in deliberations, because of course there are many different types of picture books, and a compelling story alone is not what makes every picture book excellent. The Caldecott manual repeatedly mentions "pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept." I always zoom in on the word or there. I might even argue that perceived didacticism — or whatever the implicit or explicit message is — is part of the theme or concept.

JONATHAN: Yes, there is definitely a bias toward picture books with a story, and many picture books fall outside of that — such as books for the very young; browsable, nonlinear nonfiction books; and poetry books, whether they be a single poem or a collection.

A couple more thoughts about didacticism.

- One criticism that is closely related to didacticism, but is not quite the same, is questioning whether the book is for a child audience. I don't think there's any question that all of the books we've mentioned are for children, especially when you put it beside a book like Antiracist Baby, which seems to be as much for adults as it is for their babies and toddlers. I'm not sure anyone is seriously considering that book for the Caldecott, but it's a good example of a book that has didactic intent and has a questionable child audience.

- To answer my own question, I'm not sure that didacticism is often the fatal flaw, the single thing that knocks a book out of contention, or even the biggest reason. It’s more likely to be a supporting reason. Then, too, there isn't really consensus about the reasons for not advancing books through the Caldecott process, so one committee member can dislike a book for didacticism, while another can dislike the illustrations, while a third simply liked other books better, and so on.

Can you think of other instances where didacticism may come into play, aside from this affirmation subgenre?

ELISA: Didacticism has the potential to come up in discussions around longer books and books for older readers, particularly when those books have social justice messages and/or when characters with minoritized identities are centered. The very presence of humanizing, liberating representation can be seen as “controversial” to gatekeepers with privilege and power. (I’m thinking, for example, about Malinda Lo’s research on representations of diversity in frequently challenged books.)

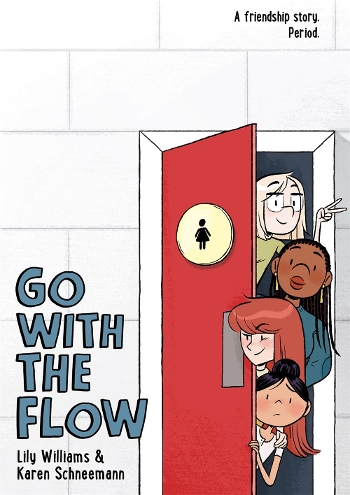

One Caldecott contender this year that is longer and for older readers is Go with the Flow by Lily Williams and Karen Schneemann. It’s an expertly drawn graphic novel with memorable characters, thoughtful coloring, effective formatting — and at the same time it sends pretty clear messages about inclusivity, the importance of questioning “normal,” and how to become a period activist and support people who menstruate. If this book gets nominated but voted down somewhere along the process, it could be due to some committee members’ biases against the page length, age range, LGBTQIA+ representation, activist messages, the limited color palette (it is aptly illustrated in shades of red), or something else entirely — or a combination of things. Whether or not it gets recognized by this year’s committee, I think you’re right that, either way, trying to point at one reason why is next to impossible.

Your #1 and #2 make me think about how, just as committee members’ votes are confidential, biases are too. And they’re often unknown even to the committee member. We are subconsciously drawn to certain storylines, genres, and affirmations and are often unaware of the biases pushing us toward or away from certain types of books, certain creators, and certain imagined readers. To me, this is where the rubber hits the road when we look at oppressive outcomes in children’s literature, whether it’s diversity in publishing houses, library departments, review journals, or award committees. It’s on each of us to do the work of learning about our biases so that we can actively work against them in order to challenge power and advocate for changes in policies and practices so that outcomes can become more equitable — and so that our behaviors and our institutions can become actively anti-oppressive.

JONATHAN: I would hope that a limited palette wouldn't be viewed necessarily as a negative. This One Summer only had a single color, too, and it got a Caldecott Honor.

But back to your earlier point. Because there is not accountability in terms of voting, it behooves each committee member to work on their own biases throughout the year. Reading and rereading and rereading has a way of allowing you to do that. Another thing I always found helpful was to compare and contrast books within subgenres. Which of all these affirmation books is the most distinguished? Then, having articulated that, I could compare it with other genres, say more story-driven picture books.

We've covered a lot of territory in this conversation. What started as a conversation on didacticism quickly evolved into a conversation about diversity, perspective, and bias. I think that's a testament to just how elusive this quality is and how much it colors our evaluation of certain books.

ELISA: Yep.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Karen MacPherson

Great and timely discussion! Thanks for your thoughtful -- and thought-provoking -- comments, Elisa and Jonathan.Posted : Nov 25, 2020 07:09

Ruth Quiroa

Thank you. There is also that little thing of aesthetic bias--what cultural and ethnic artistic styles, colors, images, etc. a committee member unconsciously (?) believes to be beautiful and will absolutely dig their feet into the ground to defend.Posted : Nov 21, 2020 08:40

DEBBIE REESE

Excellent! And glad to see it in Horn Book.Posted : Nov 19, 2020 06:12