Why Do Comics Matter? — The Zena Sutherland Lecture

Why do comics matter? At the risk of sounding completely self-absorbed, I’m going to answer this question by talking about me.

I am an Asian American cartoonist. I’m going to tell you how I became these two things: an Asian American and a cartoonist. Then I’m going to tell you how these two worlds — Asian America and the American cartooning industry — overlap.

Why do comics matter? At the risk of sounding completely self-absorbed, I’m going to answer this question by talking about me.

Why do comics matter? At the risk of sounding completely self-absorbed, I’m going to answer this question by talking about me.

I am an Asian American cartoonist. I’m going to tell you how I became these two things: an Asian American and a cartoonist. Then I’m going to tell you how these two worlds — Asian America and the American cartooning industry — overlap.

I became an Asian American by being born. I am the son of two immigrants. My mom was born in mainland China and my dad in Taiwan. They had each come to the United States for graduate school, where they met, fell in love, got married, and had me.

I grew up in a house full of stories. Both of my parents loved telling stories, and I loved listening to their stories.

I also grew up drawing. My mom tells me that I started drawing when I was two years old. I haven’t stopped.

When you take stories and you combine them with drawing, you get animation. When I was a kid, I loved watching animated shows on television and animated movies in the theater because they made me realize I could tell stories by drawing. Animation was the first form of drawn storytelling that I was exposed to. I loved animation so much that when I was in early elementary school, I dreamed of becoming a Disney animator.

That dream changed one night when I was in the fifth grade, when my mom took me to our local bookstore. Back in the 1980s, every bookstore had a spinner rack full of comics. On this night, my mom bought a Superman comic book for me from that rack.

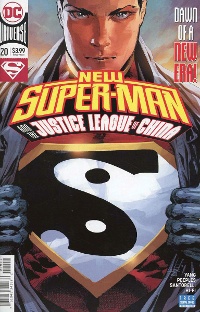

These days, I am a big fan of Superman. I’ve even gotten to write the character for DC Comics. But back in fifth grade, I thought Superman was the most boring superhero ever. That’s why my mom bought a Superman comic for me, right? Of all the superheroes out there, he is the best behaved. He is every parent’s favorite superhero.

These days, I am a big fan of Superman. I’ve even gotten to write the character for DC Comics. But back in fifth grade, I thought Superman was the most boring superhero ever. That’s why my mom bought a Superman comic for me, right? Of all the superheroes out there, he is the best behaved. He is every parent’s favorite superhero.

As disappointed as I was, I brought the comic home and read it. In the story, the atomic bomb drops in 1986. It kills off most of the planet’s population. The few remnants of humanity gather into makeshift societies that are pretty lawless, so a group of men get together, dress up in armor, and ride around the apocalyptic countryside on giant mutated dogs to fight crime. They call themselves the Atomic Knights. Superman, being Superman, is one of the survivors. He teams up with the Atomic Knights, and they have an adventure together. In the last few pages, it’s revealed that the entire story is just a dream someone’s having, but that did not stop it from completely freaking me out.

I stayed up nights thinking about Superman, the Atomic Knights, mutated dogs, and comic books; about how this combination of words and pictures did something in my head that had never happened before.

Pretty soon after, I went from being a comic-book reader to a comic-book creator. My best friend in fifth grade was a kid named Jeremy Kuniyoshi. At recess, when our more athletic friends were playing tetherball, Jeremy and I sat at the lunch table and made comic books. We came up with the stories together, I did all the pencils, and he did all the inks. We gave our originals to his mom, who would take them to work with her, wait until all her coworkers went home, and sneak photocopies for us. We took those photocopies, stapled them into issues, and sold the issues for fifty cents a copy. We made eight dollars. It was glorious. That was the beginning of my comic-book career. Jeremy has since given up on comics, but I kept going.

After college, I put out my first self-published comic, a thirty-two-pager titled Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks. It’s about a young man who gets a spaceship stuck in his nose and becomes friends with the alien driving the ship. It’s loosely based on my own life.

Ten years after Gordon Yamamoto, First Second Books published American Born Chinese, my first full-color graphic novel. The response to American Born Chinese was well beyond anything I’d expected. Librarians, teachers, bookstore owners, and comic-book fans all came out to support the book, and their support changed my life. They paved the way for me to become the full-time cartoonist that I am today.

* * *

That is how I became an Asian American cartoonist. How, then, does Asian America overlap with the world of American comic books?

I don’t have firm statistics to back up this claim, but it seems to me that Asian American creators are better represented in American comics than in any other American entertainment medium. There are a lot of us working in comics. A lot.

So many, in fact, that the parents of Asian Americans across the nation are asking, How could this happen? After all, working in comics is not one of the approved career paths. It is not doctor, lawyer, or engineer.

This phenomenon is even more perplexing when you consider how Asians and Asian Americans have historically been represented in American comics.

Chinese immigrants first began coming to the United States in large numbers in the 1800s. By the 1860s, Chinese people made up approximately ten percent of California’s population. Many Americans worried that all these immigrants would ruin American culture. They pressured the government to do something about it.

Newspapers all over the country published political cartoons commenting on the situation, featuring caricatures of Chinese people with grotesquely exaggerated facial features. These cartoons were meant to dehumanize the Chinese so that the U.S. government would be willing to act.

It worked. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act, effectively prohibiting all legal immigration from China into the United States for decades.

Dehumanizing images of Asians and Asian Americans weren’t limited to early American political cartoons. They were also found in early American comic books. DC Comics is our oldest comic-book company. The letters DC come from Detective Comics, the company’s longest-running series, which began in 1937.

Detective Comics #1 features on its cover Chin Lung, a Chinese supervillain bent on taking over the Western world. Chin Lung has slanted, blank eyes and a pointy-toothed grin. He was designed to play on Americans’ fear of the Chinese. Today, we call these sorts of characters “yellow peril” villains.

Early American comics were replete with yellow peril villains. The most outrageous of these is probably Egg Fu. Like Chin Lung, Egg Fu is a Chinese supervillain bent on taking over the Western world. He is also literally a bright-yellow man-sized egg with a Fu Manchu mustache.

Every now and then in early American comic books, Chinese characters did show up on the hero side of the hero-villain divide. During World War II, a company called Quality Comics published the adventures of the Blackhawks, a team of superhero pilots who fought for the Allies. At the height of their popularity, the Blackhawks outsold all other comic-book characters but Superman.

Blackhawk members represented different Allied nations. There was a British Blackhawk, a Polish Blackhawk, a French Blackhawk, and even a Chinese Blackhawk. All but one of the Blackhawks wore snazzy blue pilot uniforms. The Chinese member, named Chop-Chop, wore a green and yellow suit that bore more resemblance to a circus performer’s costume than to traditional Chinese clothing. He wore his hair in a braid despite the fact that Chinese men had ended that practice decades before. Chop-Chop even had the exaggerated facial features of a political cartoon of the 1800s. Even when Asians and Asian Americans were allowed to fight for good, their depictions were problematic.

Things did get better. In the 1970s, America went through a collective obsession with martial arts, in large part because of a charismatic Chinese American actor named Bruce Lee. Comic-book companies catered to this obsession with a host of Asian martial arts characters. The most prominent of these is probably Shang-Chi, the Master of Kung Fu, who is essentially the Marvel Universe version of Bruce Lee.

Martial arts characters come with a particular set of stereotypes, but on the whole, I believe this was an improvement over what came before. Most of these characters were heroes, and they were portrayed as three-dimensional human beings with relatable desires, fears, and flaws.

In the 1980s, the G.I. Joe franchise was a bastion of diversity, with an array of cultural representation that was well ahead of its time. There were Asian and Asian American characters both on the G.I. Joe team and in the villainous Cobra organization.

I always wondered why G.I. Joe was so diverse, and as an adult I discovered the answer. Many of those early G.I. Joe comic books were written by a Japanese American writer named Larry Hama, who wanted to represent as many different aspects of America as possible.

In the 1990s, the X-Men were another bastion of diversity. As far as Asian and Asian American representation goes, there was Sunfire, a Japanese mutant who could shoot fireballs out of his hands; Jubilee, a Chinese American mutant who could shoot fireworks out of her hands; and Psylocke. Psylocke was actually born British, but after coming to America and joining the X-Men, she was kidnapped by ninjas and given an Asian body, so I’m claiming her as an Asian American.

* * *

No doubt about it, representation has gotten better. However, it still doesn’t answer the question: why are there so many Asian American creators in the American comic-book industry?

I’m going to share with you two of my own theories. I am a cartoonist, not a researcher, so please take these with a grain of salt.

My first theory comes from the very structure of the comics medium. Comics, by definition, are a blend of words and pictures. In Western cultures, words and pictures have traditionally been seen as two separate disciplines. The people who were good at words were not the same people who were good at pictures. When words and pictures did come together, the results were often judged as vulgar, as in advertising, or childish, as in picture books. (To be clear, I do not believe advertisements to be inherently vulgar, and anyone who belittles picture books has never tried to make one.)

The same is not true of Asia. If you look at Chinese brush painting or Japanese printmaking, the image is always paired up with words. A work is not considered complete unless both elements are present. A work is not considered masterful unless both elements are masterful.

Maybe Asian Americans are drawn to comics because our cultural heritage prepares us for this medium that combines words and pictures.

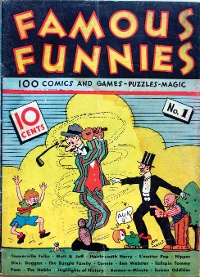

My second theory comes from the origin of the comic book. The publishing format that we now think of as the comic book was created in 1933. (Called Famous Funnies, this first comic was the brainchild of a couple of printing-press employees at Eastern Color Printing.) In less than a decade, comics became a mass medium, selling millions of copies every month.

My second theory comes from the origin of the comic book. The publishing format that we now think of as the comic book was created in 1933. (Called Famous Funnies, this first comic was the brainchild of a couple of printing-press employees at Eastern Color Printing.) In less than a decade, comics became a mass medium, selling millions of copies every month.

Many of the creators who were working in the early days of comics, whom we now consider masters of the medium, were the children of immigrants. Specifically, they were the sons of Jewish immigrants. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman. Bob Kane (born Robert Kahn) and Bill Finger created Batman. Stan Lee (born Stanley Lieber) and Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) created most of the Marvel Universe. They were all the sons of Jewish immigrants.

I don’t know whether or not they did it consciously, but they all put pieces of their own cultural heritage into their stories. Take Superman, for example. When Siegel and Shuster created him in 1937, they weren’t just creating a character, they were establishing a genre. Superman is the very first superhero ever. Every other superhero follows in his footsteps.

The central dynamic of Superman’s existence is his dual identity. Most of the time, when people see him on the streets of Metropolis, they think he’s an “average American.” Deep down, though, he knows he’s not. He knows he’s from another place. He knows he’s an alien, an immigrant, a foreigner. And just to get through his day, he has to hide this fact from the people around him.

This hiding of who you are, this navigating between two identities, was a daily reality for Siegel and Shuster and all of their Jewish family and friends, here in America and also back in Europe. After all, when Superman was getting started in the late 1930s, so was World War II.

Superman’s story felt very familiar to me. I, too, used two different names: an American name at school and a Chinese name at home. I spoke two different languages — English at school and Mandarin at home — and lived under two different sets of cultural expectations. I knew what it was like to navigate between two identities.

Maybe this is another reason why so many Asian Americans are drawn to comic books. From their very beginning, comic books have been for outsiders. In the early days, voiceless sons of Jewish immigrants were able to find their voices in comics. I believe the same is true today for Asian Americans—and, really, not just Asian Americans, but “outsider” storytellers of all kinds. Like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, many of us are able to find our voices in comics.

* * *

Comic books matter because stories matter, and comics are a way to tell stories.

Comic books matter because stories matter, and comics are a way to tell stories.

Each of us has this voice in our heads that is constantly taking the events of our lives and weaving them into a narrative, into a story. This is how we humans make meaning.

Stories matter. How we are portrayed in the stories of our culture matters because those stories influence the narrative in our heads. They affect the aspirations we allow ourselves to have. They affect what risks we are willing to take.

Stories also influence how others see us. They affect how the people around us receive our words, our ideas, and our humanity. When they look at us, do they see Chin Lung? Do they see Egg Fu? Or do they see a three-dimensional human being?

So let’s tell better stories about ourselves. And let’s be willing to listen to the stories of others.

Stories matter.

From the November/December 2019 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. This article is adapted from the 2019 Zena Sutherland Lecture, delivered on May 3, 2019, at the Harold Washington Library Center in Chicago. See also Roger Sutton's 2017 interview with Gene Luen Yang and more by and about the author/illustrator.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!