Welcome to the Horn Book's Family Reading blog, a place devoted to offering children's book recommendations and advice about the whats and whens and whos and hows of sharing books in the home. Find us on Twitter @HornBook and on Facebook at Facebook.com/TheHornBook

Words for Flora's Mother (and Other Imperfect Parents)

Often, when I mention that I have five children, people ask, “How do you do it all?” I sometimes quote a response I’ve heard from Donna Jo Napoli, fellow writer, professor, and mother of five:

“How do I do it all? Badly.

“How do I do it all? Badly. You could eat off my kitchen floor…for weeks.”

How I do it all is that I don’t do it all at once. As I sit down to write, my kitchen is a mess, and my kids are at their other house with their other mom (my ex-wife). I miss my children, but I’m also grateful to be able to work like hell on the days they’re gone and really focus on them when they’re here. Or at least that’s what I try to do.

Shared reading enables us to slow down and enjoy one another’s company in the midst of our busy, transition-laden routines. I’m currently reading Kate DiCamillo’s 2014 Newbery Medal winner Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures with my four youngest children. I read the ARC by myself and knew my kids would be pulled in by the exact elements that made me initially skeptical. A superhero squirrel? Quasi-comic-book art? Not my cup of tea. But I also felt myself yearning to deliver the message of unconditional love that’s at the heart of the book: “Nothing / would be / easier without / you.”

Shared reading enables us to slow down and enjoy one another’s company in the midst of our busy, transition-laden routines. I’m currently reading Kate DiCamillo’s 2014 Newbery Medal winner Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures with my four youngest children. I read the ARC by myself and knew my kids would be pulled in by the exact elements that made me initially skeptical. A superhero squirrel? Quasi-comic-book art? Not my cup of tea. But I also felt myself yearning to deliver the message of unconditional love that’s at the heart of the book: “Nothing / would be / easier without / you.”Sometimes I worry my kids might think I feel differently. There are days when I am snappish or grouchy or just plain overwhelmed by balancing work and motherhood. DiCamillo’s novel has me thinking about depictions in children’s literature of less-than-ideal parents and what they communicate about family life to child and adult readers alike. I don’t mean Roald Dahl-ian parents like poor Matilda Wormwood’s dreadful mother and father, but more like Flora’s divorced parents or her friend William Spiver’s mother and “her new husband.” These secondary, or even offstage, adult characters are believable in all their flawed humanity. Their failings help define Flora’s story as she grapples with the shortcomings of the adults in her life, but DiCamillo paints her characters with such subtlety that the lesson doesn’t overwhelm the text.

On the flip side, many books have the mommy or daddy endlessly reassuring their little Stinky Faces and Nutbrown Hares about their love-you-forever love. Such constructions of adulthood don’t reflect the times we parents fail, as Flora’s mother does. They instead present us with visions of what we might be on our best days.

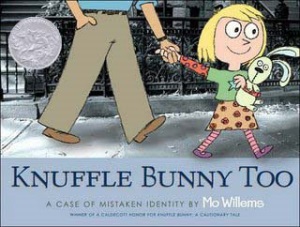

It’s the rare person who rises to the level of idealized parenting achieved, for example, by the father in Mo Willems’s picture book Knuffle Bunny Too. When daughter Trixie realizes, in the middle of the night, that she mistakenly took home the wrong Knuffle, Daddy agrees to an on-the-spot stuffed-bunny exchange. Would I do such a thing? Not a chance. Faced with such a scenario, I’d tell my kid that we’d sort things out in the morning. If I were feeling very generous, I’d tuck her back in with another stuffed animal. And I wouldn’t go back and forth in some reverie about “and if the moon could talk” or whatever. Good. Night.

It’s the rare person who rises to the level of idealized parenting achieved, for example, by the father in Mo Willems’s picture book Knuffle Bunny Too. When daughter Trixie realizes, in the middle of the night, that she mistakenly took home the wrong Knuffle, Daddy agrees to an on-the-spot stuffed-bunny exchange. Would I do such a thing? Not a chance. Faced with such a scenario, I’d tell my kid that we’d sort things out in the morning. If I were feeling very generous, I’d tuck her back in with another stuffed animal. And I wouldn’t go back and forth in some reverie about “and if the moon could talk” or whatever. Good. Night.And yet, even if I can’t pretend to aspire to Trixie’s daddy’s selflessness, I absolutely see a reflection of myself in how plain exhausted he looks when Trixie rouses him from a deep sleep. Indeed, some of the most rounded portraits of parents in picture books come in stories about them trying to get their little ones to “go the f*ck to sleep.” Amy Schwartz’s Some Babies, David Ezra Stein’s Interrupting Chicken, and Janet S. Wong’s Grump (illustrated by John Wallace) are just a few that conclude with beleaguered, fatigued parents nodding off while trying (and failing) to put their little ones to bed.

And why are they so tired? Well, because the days leading up to those fraught bedtimes can be…long. I have a soft spot in my heart for Marla Frazee’s not-so-flattering but oh-so-familiar depictions of parents at the mercy of their Boss Baby; a mother driven nuts by her little girl (Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild! by Mem Fox); and an exasperated Mrs. Peters who can’t satisfy everyone’s tastes (The Seven Silly Eaters by Mary Ann Hoberman). And high on my list of picture book illustrations that capture not the drama of difficult moments but the tedium of daily routines is a vignette from Amy Schwartz’s slice-of-life picture book A Glorious Day. The droll text reads: “At home Henry and his mother play trains. Henry is the big train and his mother is the small train. All morning long.” I can practically hear Henry’s mother meditating on a refrain from another train book — “I think I can, I think I can” — as she puts in quality floor time with her kid.

And yet, she’s hanging in there. The same cannot be said of Flora’s mother. Until book’s end, she’s so wrapped up in herself and her career as a romance novelist that she is blind to her daughter’s needs. She might find kinship with the mother of another Flora, the star of Jeanne Birdsall and Matt Phelan’s picture book Flora’s Very Windy Day. I’ve read it with my children and have recognized myself in its depiction of a mother driven not wild but to weary despair as, instead of helping her quarreling kids solve their dispute, she shoos them outside while trying to get some work done. Is she writing a romance novel on that laptop? I don’t know. But I do know that she, like the other Flora’s mother, and like me sometimes, is not having a terribly glorious day of attentive mothering.

And yet, she’s hanging in there. The same cannot be said of Flora’s mother. Until book’s end, she’s so wrapped up in herself and her career as a romance novelist that she is blind to her daughter’s needs. She might find kinship with the mother of another Flora, the star of Jeanne Birdsall and Matt Phelan’s picture book Flora’s Very Windy Day. I’ve read it with my children and have recognized myself in its depiction of a mother driven not wild but to weary despair as, instead of helping her quarreling kids solve their dispute, she shoos them outside while trying to get some work done. Is she writing a romance novel on that laptop? I don’t know. But I do know that she, like the other Flora’s mother, and like me sometimes, is not having a terribly glorious day of attentive mothering.Phelan’s art deftly and powerfully conveys the emotions underlying the conflict. In the first double-page spread Flora, on the verso, is Eloise-like in her rage, with red emanata surrounding her. Little brother Crispin sits, posture alert, at a safe distance by a messy art table (as we saw on the dedication page, he spilled his sister’s paints — again!), his sidelong gaze directed at Flora. He’s clearly seen her blow her top before. Their mother is far to the right of the composition, turning away from her computer screen with a wan, defeated expression. While Flora is unquestionably the focus—the other characters’ eyes are on her, and her erect, outraged depiction demands attention—I can’t help but home in on this mother. I know her. I’ve been her. I want to give her a hug.

Do my children notice this mom? Not really. And who can blame them? Flora is a force to be reckoned with, and my kids are much more interested in the sibling conflict. When they once did shift their attention to the mother, it was to remark, “It’s not fair!” when she insists Flora take Crispin outside with her. “Give her a break!” I said in a mothers-of-the-world-unite sort of way.

The wind carries Crispin away, and Flora resolves to retrieve him: “My mother wouldn’t like it if I lost him.” My then-nine-year-old daughter Emilia empathetically piped up, “And Flora would miss him, too, even if he spills her paints.” On the penultimate spread, Flora and Crispin return home, and their mother, channeling Max’s mom and his “still hot” dinner, has chocolate chip cookies waiting. The story could end there — the text does — but Phelan delivers a heartwarming visual coda on the final page-turn that shifts attention away from the mother’s act of apology and back, where it belongs, to the sibling dynamic. The couplet of pictures first shows Flora and Crispin sitting apart and eating their cookies, then leaning into each other, not making eye contact or smiling, but with the closeness between their little bodies communicating forgiveness. The scene is familiar to me as both an older sister and as a mother of children who bicker and make up, who love one another through and despite times when they fail or hurt or disappoint one another. “Nothing would be easier without you” these pictures seem to say. “Even if you spill my paints.”

I appreciate how this wordless closing eschews a mama’s mea culpa as resolution to the story. After all, children’s book readers aren’t terribly interested in a mother’s emotional story arc. I recall with chagrin one time when I was sick with the flu — and also sick and tired of kids bickering before bedtime — that instead of letting my children choose our shared reading material, I dramatically pulled William Steig’s Brave Irene off the shelf, self-indulgently recalling how its intrepid child protagonist lavishes her ill mother with affection and support. “Oh Mom-Mom,” Emilia said, after I’d read a few pages. “We have not been so nice as Irene.”

I appreciate how this wordless closing eschews a mama’s mea culpa as resolution to the story. After all, children’s book readers aren’t terribly interested in a mother’s emotional story arc. I recall with chagrin one time when I was sick with the flu — and also sick and tired of kids bickering before bedtime — that instead of letting my children choose our shared reading material, I dramatically pulled William Steig’s Brave Irene off the shelf, self-indulgently recalling how its intrepid child protagonist lavishes her ill mother with affection and support. “Oh Mom-Mom,” Emilia said, after I’d read a few pages. “We have not been so nice as Irene.”And did that make me feel any better? Of course not. I felt like a jerk. Guilt-tripping one’s children into compliance or sympathy through passive-aggressive bedtime reading selections isn’t a terrific parenting strategy. I can report, however, that my other kids weren’t so moved. “You’re not really that sick,” Stevie said. “Can I choose the next book?” Caroline asked. And on we went.

I know my kids won’t recall their childhoods — even filled as they are with books, and play, and each other, and parents in two houses who adore them — as devoid of parenting failures, lacking in conflict or hurt, and overflowing only with wonder and whimsy. And I know that my own faults contribute to some of the less-than-ideal moments they’ll recall. That’s a hard pill to swallow, and as I (re)read DiCamillo’s book and anticipate Flora’s reconciliation with her mother, I’ve come to think that although this resolution may be a comfort to child readers who see the child protagonist’s wish fulfilled in confirming her mother’s love, it also gently guides them toward acceptance of flawed adults. Forgive us, children, books with such parents say; we know precisely what we do, and we feel like crap about it. DiCamillo’s novel avoids having the final words be delivered in a parental voice begging filial pardon. Instead, the closing poem is a superhero squirrel’s affirmation of his devotion to the girl who saved him.

Adoptive parents like me frequently encounter well-intentioned but misguided comments implying that we saved our kids. “They’re so lucky to have you” is the refrain. The truism that their other mom and I often resort to is that we are the lucky ones. To stretch and invert Ulysses’s line to Flora, nothing would be harder to imagine than life without them. Paraphrasing DiCamillo: “It’s a miracle. Or something.”

And if I lose sight of the miracle of this modern family of mine, there’s nothing like settling in with a book to redirect our attention away from the tumult of our own foibles and failings toward the common ground of others’ stories. Book bonding, you might call it. We put aside quarrels over who had more time on the Xbox, why it’s so hard to just bring the freaking laundry downstairs, and whatever is “not fair!” at any given moment, to read about everything from very windy days, to bunny-exchanging daddies, to mothers driven wild, to superhero squirrels. And, holy bagumba, as Flora might say, I’ll love those times forever — to the moon and back! The kitchen floor can wait.

From the May/June 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!