2022 Newbery Medal Acceptance by Donna Barba Higuera

If someone had told me as a child that not only would I one day write a book, but that book would sit alongside those “golden-sticker books” like A Wrinkle in Time or Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, I would have said, “That’s impossible. It could never happen for a kid like me.” But here I am.

"It could never happen for a kid like me." Photo courtesy of Donna Barba Higuera.

If someone had told me as a child that not only would I one day write a book, but that book would sit alongside those “golden-sticker books” like A Wrinkle in Time or Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, I would have said, “That’s impossible. It could never happen for a kid like me.” But here I am.

The words I could, should, might say tonight have haunted me. Will I put my foot in my mouth? A dear friend of mine told me, “If you’re worried about putting your foot in your mouth, just wear really big shoes.” So, I am.

The word cuentista means storyteller. But as words are often nuanced, the connotation for cuentista is that this particular storyteller might not be the most reliable of narrators. A cuentista might be twisting or bending the tale to make the story more colorful.

For cuentistas, those stories, or cuentos, often begin with a saying, something to let you know you’re about to go on an adventure, like: “Habia una vez” / “Once upon a time.” Or: “Cuando los animales hablaban” / “In the time when the animals spoke.” And the cuentos end with something like my favorite: “Y colorín colorado, este cuento se ha acabado,” which doesn’t really have a direct meaning, but is something like, “My many-colored, feathered friend, now the story has found an end.” Or: “Esto es verdad, y no miento, como me lo contaron lo cuento,” meaning, “This is true, I cannot lie; I told it to you as it was told to me.”

How does a storyteller go from finishing their story with “This is not a lie” to how I felt as a child when I made up my first stories? I grew up thinking I was indeed a liar. I’d learned in Sunday school that there were different kinds of lies; lies by omission, compulsive lies…white lies. I discovered I lied in a few ways. I lied by “fabrication,” and I was a “bold-faced liar.” My Sunday school teacher said, “A lie is a lie” and “All sin is the same.”

So I spent much of my childhood convinced I was going to hell. Still, even with the threat of fire and brimstone, there was no redemption for me. I couldn’t stop telling these lies.

The first lie I remember telling, at the age of five, was both a fabrication and a bold-faced lie. I looked my mom, then dad, then grandmother, then elderly neighbor dead in the eye and swore to each of them separately that alien ships had landed in our yard the night before. As I told of the arrival of the aliens to four different adults, each time the story grew. First, they’d simply landed, then took off quickly. By the fourth rendition, I proclaimed that the aliens had an extensive on-ship visit with me, where they imparted an important message for my parents: that they should let me eat as much sugar cereal as I wanted. It is not lost on me that my first attempt at story was science fiction.

And this was the first of many of these stories. None of these trusted adults ever stopped me from my lies. Instead, they’d smile and ask, Then what happened?

When I was a bit older, I collected bags of iridescent shards of glass from the ground outside an old, abandoned home on the corner. To me, they were not cracked and kaleidoscopic from being baked in the scorching desert sun. Fairies and gnomes must be traveling from England and Ireland to my tiny oil and agricultural town of Taft, California, to mine this new kind of treasure. I had to beat them to it. One day, my mother discovered my hoard of rainbow treasure, which I’d collected into one massive pile. I explained to her that I couldn’t tell her where I’d found it, as it was magic. Only children could find the treasure. (It was actually because I knew she’d ban me from the yard of the abandoned home.) That day, she didn’t ask, Then what happened? Instead, she placed my fortune in the garbage. How could she only see a toppling mound of shredded paper lunch sacks full of dangerous, splintered glass?

Once I was allowed to go past the end of our block, I found my way into the restricted pioneer cemetery in the desert hills behind our home. Using the faded and crumbling tombstones, I made up stories about its inhabitants. If the grave’s marker had no name, I made one up. By the time I’d learned how to add and subtract double digits, I could calculate the age of the person under the headstone. I’d make up reasons for each as to why they were in this small town in the first place. Babies were given full and magical lives filled with adventure.

I didn’t want to think of myself as a liar. But the Sunday school teacher said I was. So where did I learn this deviant behavior? What were the bad influences that urged me to tell stories and make things up? I have some people I’d like to tell you about.

My sweet grandmother, Maria (Mary) Barba Salgado Higuera, did not attend school beyond elementary school. The daughter of a farm laborer in Central California, at age eleven she was sent away to work in a hotel as a maid to help support her family, when her father, Francisco, died. We can say, “This was not so uncommon back then.” But it was not so long ago. I try to imagine myself at the age of eleven, and how she must have felt to be separated from her family. If I were her, how would I have comforted myself? Well, Mary Barba Salgado Higuera told me: she found her comfort in stories.

To a distant city, she carried little but the folklore, culture, and stories of her family. A true cuentista, she told other workers her cuentos, often twisting the truth of those stories and who her ancestors truly were to make them sound more magical. As a child, I begged her for these cuentos. Some of them were otherworldly, like the story of El Conejo, the rabbit on the moon. Some were horrifying and too close for comfort, like el cucuy, the boogeyman who lived in the cactus pot in my bedroom at her home. Many of her stories were of the hardships she and her family had encountered.

My mother, Patsy June, told me the stories of her family’s move from Oklahoma to California, like so many after the Dust Bowl; how when they arrived with nothing, her father built a home out of cardboard, and they lived in a shantytown called Pumpkin Center until he found work in the oil fields. My mom said this was when she most missed their farm in Oklahoma. She wove unbelievable tales of make-believe creatures called flying squirrels. She told stories of how she and her brothers ate sugarcane from the stalk. She swore they saw mysterious spooklights, thought to be the spirits of separated soulmates. Those things I thought were lies, like flying squirrels or eating sugar from a stalk instead of a box, turned out to be true. Maybe even the spooklights.

Esther Grigsby was a woman in her eighties who lived next door. She wouldn’t let me call her Grandma or Auntie Esther, so I simply called her Grigsby. Grigsby had lavender hair and wore faded cotton housedresses, Keds, and rhinestone earrings. Once a day, we’d sit on her porch. The clink of glass on glass would echo from her kitchen, and she’d bring out a jar of homemade pickled okra, and I knew a story would begin shortly. With okra juice dripping from our hands, we’d look out at her garden and mulberry tree. She’d curse at the jackrabbits who snuck in from the desert to eat her vegetables. She told me they’d swore at her first. She’d hold entire conversations with the birds and rabbits in her yard, and go into great depth about the discussions she’d had the night before.

A gazing ball under the mulberry tree held a secret world beneath — this was where these talking animals were originally from. The gazing ball was not made of iridescent or transparent handblown glass. It was a large round rock she’d found in the desert and painted silver. But she assured me that the gazing ball and everything around it were all magical, and if I spoke to the animals and plants and trees, that one day they would speak back. They’ve yet to speak back to me, but I will continue until that day arrives.

My father told me a bedtime story every single night. His stories were wild adventures and portal fantasies through the bathtub drain or an electrical outlet ushering my sister and me out of the desert and into lush and green, or snowy, places.

Once, my well-meaning fourth grade teacher gave an assignment to twenty-five kids, most of whom had fathers who worked in the oil fields. We were to give an oral presentation on a “famous person we were personally related to.” When I came home distraught, as we had no famous relatives that I knew of, my father suddenly recalled that Al Capone was my great-uncle. That presentation, apparently a lie of fabrication, got both me and my father in trouble.

These strong parents and grandparents and the stories of my other elders and ancestors: how can one live up to that? Are all these stories true? No one can know for sure. They were spinners and weavers of cuentos; cuentistas y cuentistos.

Aside from the oral tradition of storytellers in my own family, I had others who told me stories. Writers.

And there were many. The first book I remember taking me to another place was a picture book where an earthworm could be a farmer, drive an apple car, and fly an airplane. The first book where I remember sounding out words and sentences was with a mouse named Frederick who, like me, would rather stare at sunbeams and create stories and colors in his imagination than do chores. I moved from the daydreaming mouse to paragraphs where I joined orphans on a train car, then to longer chapters where my love of science fiction soared into the universe. While not everyone shared in my love of sci-fi, and I was often afraid to share my love of science fiction with others, I traveled with Meg Murry over and over again on all her adventures to battle evil in outer space and other cosmic dimensions from my dusty porch in that small desert town.

With these and other books, the floodgates of all kinds of stories opened for me. I traveled to cities and countries and worlds too numerous to count. In books, I found something else. There were others like me. The writers of these books were doing what I was doing, making stuff up. Did they think they were going to hell, too? If so, would hell be so bad? We could all sit around a firepit and lie to one another all night long!

I know now that I was, they were, all storytellers. Cuentistas.

Each of us in this room has books we’ve read or stories told to us by a teacher or parent or grandparent. Now we have the power and, yes, responsibility to pass those stories along. We have the privilege of creating, or placing books in the hands of readers, not just a book they will love but, if you know their life circumstance, as my town’s librarian, Mrs. Hughes, knew mine, a book that child might need.

As librarians and educators and writers, we get the opportunity to give kids books on topics and worlds they might not understand. We can open the universe to them, so the strange story of the Mexican boogeyman told by a fire, or cuentos of talking jackrabbits told while sitting on a back porch with a spear of pickled okra in hand, will also feel like home to you and those young readers.

That is the power of story and cuentos.

But from that first alien invasion UFO lie…cuento I told as a child bloomed this book of Petra and her love of story, folklore, and mythology. (Naysayers whispering: But it’s sci-fi.)

At the heart of The Last Cuentista are many things aside from science fiction: the love of family. The priceless gifts that stories and storytelling bring us. The dangers of conformity. Cherishing our individuality. Being proud of all we are. What it truly means to be human. And how those stories handed down to us by our parents, grandparents, even the ones we made up, the books in our libraries and human archives, are one of the most valuable things humanity possesses.

At the heart of The Last Cuentista are many things aside from science fiction: the love of family. The priceless gifts that stories and storytelling bring us. The dangers of conformity. Cherishing our individuality. Being proud of all we are. What it truly means to be human. And how those stories handed down to us by our parents, grandparents, even the ones we made up, the books in our libraries and human archives, are one of the most valuable things humanity possesses.

So I must speak about the literary elephant in the room.

This book was written a few years ago, but it eerily speaks to current events. The erasure of history, art, and stories and books, on the other side of the world, but also in our own country.

Why did I write this attempt at erasure of story in The Last Cuentista in the first place? Because it was what I feared most.

If you were leaving Earth and could take one thing along, what would that be? For me, that is story. Books. Folklore and mythology. But also the memories of the cuentos of Grigsby, my grandmother, my parents, and the books my local librarian, Mrs. Hughes, handed to me; what if someone wanted to destroy and erase those things? To most of us in this room, the idea of a world without story is not only terrifying, it is the thing that frightens us most.

In real time, now, this is happening. How did I know? I didn’t. It is as simple as the thing I fear most finding its way into my character Petra’s greatest fear. Erasing and banning our stories is a pattern that’s repeated itself. A pattern I naively thought we had grown beyond.

I think much of what is happening with erasure of books now is based in fear. For some, it is easier to set aside or look away from things we don’t understand or can’t comprehend. But I will allow Petra’s thought to be the final word on this topic:

I can’t tell if she’s trying to forget, or to remember. Maybe stories are there to help us do both. I know stories can’t always have happy endings. But if there are chances for us to do better, we have to say out loud the parts that hurt the most.

When I was writing The Last Cuentista, I didn’t believe anyone would understand this strange book of a girl with a love of story, Mexican folklore, and mythology interwoven with science fiction and dystopia. But even to those who say (whispering again), But I don’t like sci-fi, Petra’s story is all of ours. Why? Because it speaks to all of us of being proud of all of who you are. Being unapologetic, unashamed, unafraid to be a cuentista. It speaks to how it really does take courage to put the stories of those who weave tales into the hands of children. Librarians, thank you all for your courage.

There are so many others I must thank for their courage and support in bringing children’s books into this world. I have found something in my adult life as a writer that I didn’t always have as a child. Those who love writing and books and storytelling are the kindest, most generous people. It turns out there are many who love and appreciate those of us who tell bold-faced and fabricated lies. I have formed a treehouse of trust that’s getting quite cramped in the best possible way. And there are many I need to acknowledge.

Thank you to the ALA, ALSC, the Newbery committee — Thaddeus Andracki and all the Newbery committee members for your dedication and for the work you do for children’s literature.

I must mention my newest friends, who I’m sharing this night with: Andrea and Jason, Rajani, Kyle, Darcie.

But I’ve discovered my new friends, not just us New-berys. I’ve had some Past-berys reach out. Thank you for your kindness and words of advice: Linda Sue Park, Matt de la Peña, Meg Medina, Tae Keller, Jerry Craft, Kelly Barnhill, Katherine Applegate, Erin Entrada Kelly.

Thanks to my dear friend and agent, Allison Remcheck, who with the subtlest of nudges and deepest words of encouragement helps me create. Thank you. And thank you to my team at Stimola Literary Studio — Rosemary Stimola, Peter Ryan, Alli Hellegers, Erica Rand Silverman, Adriana Stimola, and Nick Croce.

Thank you to Nick Thomas, who, after I wrote Lupe Wong Won’t Dance, a story about a stubborn girl who’d rather eat slugs than square dance, asked, “So what are you working on now?” I was afraid to tell him how the story prompt of my dreams — “Take a traditional fairy tale and make it sci-fi” — had transported me from Lupe Wong, a bungling, social justice–minded middle schooler, to Petra, who’s on an interstellar journey to save the very essence of storytelling. How had I gone from Lupe and “my gym shorts burrow into my butt crack like a frightened groundhog” to Petra describing her final night on Earth with her abuelita, saying, “Lita tosses another piñon log onto the fire. Sweet smoke drifts past us into the starry sky”? But Nick didn’t flinch, and instead said, “Okay. Let’s do it!” I know the risks you’ve taken on my stories, and you took them anyway. Thank you, friend.

I must thank the rest of my team at Levine Querido: Arthur A. Levine, Antonio Gonzalez Cerna, Irene Vázquez, Meghan McCullough, and Maddie McZeal. Mil gracias.

There are many others who helped this book into the world in one way or another. David Bowles, Aurora Humarán. The designer of this book, Richard Oriolo, and production developers Leslie Cohen and Freesia Blizard.

I want to thank Yuyi Morales for allowing the excerpt from your beautiful book Dreamers to be included in The Last Cuentista.

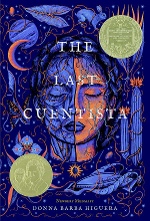

Raxenne Maniquiz, thank you for creating this beautiful, breathtaking cover. The best blurb I’ve gotten so far has been given by my daughter, Sophia. “Mom, this cover is so beautiful, your book could be horrible, and kids will still read it.”

Thank you to my writing family, my critique group, The Papercuts. Cindy Roberts, Jason Hine, David Colburn, Maggie Adams, Elinor Isenberg; and my husband, Mark Maciejewski, who also happens to be my partner in life. I get to be married to someone who loves children’s literature and books and writing and storytelling as much as I do. Thank you, Mark, for making me laugh all the time, and for being my best friend in the treehouse.

Thank you to Las Musas, who have been a kind of support and family in other Latina writers I never expected to find on this journey.

And to my children, who are the reason for all that I do. I hope this makes you even a tiny bit as proud as you make me. And thank you to my parents, thank you for encouraging my big imagination.

Mrs. Hughes, wherever you are in the universe, thank you for the smile that lit up your face each time I walked into your library. You probably had that smile for every child. But thank you for letting this freckle-faced, gap-toothed kid, who often felt invisible, know that you saw her. Thank you for handing her the books you knew she’d like, and perhaps some you knew she needed.

Finally, to that child out there who has wild lies…I mean stories, swarming in your mind. Maybe you think your cuentos could never be real books. And that one of those books could sit alongside a gold-sticker book that burst into life from a dusty desert porch. I say this: tell your cuentos proudly. Because it is possible. It happened to this kid.

Y colorín colorado, este cuento se ha acabado.

Thank you.

Donna Barba Higuera is the winner of the 2022 Newbery Medal for The Last Cuentista, published by Levine Querido. Her acceptance speech was delivered at the annual conference of the American Library Association in Washington, DC, on June 26, 2022. From the July/August 2022 issue of The Horn Book Magazine: Special Issue: ALA Awards. For more speeches, profiles, and articles, click the tag ALA 2022.

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Single copies of this special issue are available for $15.00 including postage and may be ordered from:

Kristy South

Administrative Coordinator, The Horn Book

Phone 888-282-5852 | Fax 614-733-7269

ksouth@juniorlibraryguild.com

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!