Field Notes: I Gave My Life to Books: A Journey Through the World of Children's Literature

Maurice Sendak once said, “As a child, I felt that books were holy objects, to be caressed, rapturously sniffed, and devotedly provided for. I gave my life to them.” That’s how I have always felt as a teacher and parent too.

Maurice Sendak once said, “As a child, I felt that books were holy objects, to be caressed, rapturously sniffed, and devotedly provided for. I gave my life to them.” That’s how I have always felt as a teacher and parent too. I began my teaching career in Newark, New Jersey, where I had moved after graduate school to help start a community-based school, with the intention of offering an alternative to the local public schools. Somehow I knew, from the start, the importance of books in children’s lives, and I started a Reading Is Fundamental program. I would drive up to a local book distributor, fill my car with new picture books, return to school, and begin building a library in my office — not a lending library but rather a giving library, where every two weeks children could come and pick out two books to keep. For many kids, these were the first books they had ever owned.

That spirit of putting good books into the hands of children has been with me ever since, from Newark to a one-room schoolhouse in Rhode Island to various other schools over the forty-five years of my teaching career and my life as a parent of two. By the time we had children, my wife and fellow teacher, Robin Smith, and I were well-versed in Jim Trelease’s The Read-Aloud Handbook, the most influential book in our lives as parents and teachers. Following Trelease’s lead, we read aloud to Julie and Andrew every single night, practically from the time they were born until sixth grade, when they got too busy with homework and their school lives.

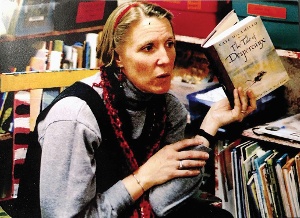

Robin Smith reading to her second graders at school. Photo: Adrienne Parker.

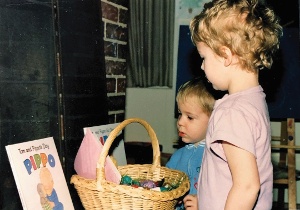

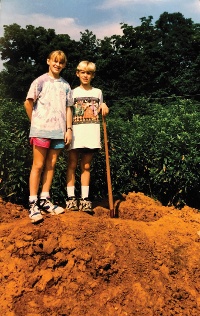

Ours was a house filled with books. Helen Oxenbury’s Tom and Pippo books were early loves. I remember Julie liking Dr. Seuss’s Hop on Pop, except for the “Dad is sad” page; she always flipped on to the next page, not wanting to think of Dad being sad. Julie wrote and illustrated her first book when she was four, titled “Fat Men Come to Eaglebrook,” after I had read her Daniel Pinkwater’s Fat Men from Space. And Julie and Andrew built their own Roxaboxen in the fields behind their grandparents’ house after loving Alice McLerran and Barbara Cooney’s picture book. Later, novels by E. B. White, L. Frank Baum, and Lloyd Alexander were treasured. We read aloud to our children every evening, encouraged their own reading, and let them stay up late if they were reading in bed.

Books as Easter presents; Julie and Andrew Schneider creating their own Roxaboxen. Photos: Robin Smith.

Our practice at home became our practice in school, knowing that children who hear good language and read up a storm develop their own strong language resources to draw upon as writers and students. I can usually tell in my middle-school classes which students have grown up in houses full of books with parents who read aloud to them over the years. So, we read aloud in school and had classroom libraries, allowing kids time to read in class. Robin read aloud two hundred picture books every school year, along with a chapter book every two or three weeks.

In middle school, with several classes to teach, I didn’t read aloud entire books, but I always shared essential scenes, passages, and chapters. Last year, for example, we read Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down, a novel in verse that has become one of my favorite books to read with my classes, one that I will always teach. I had the class read it on their own first, then I read aloud the essential ghostly elevator passages, in which each ghost imparts a message of some sort that may (or may not) influence the protagonist’s decision at the end of the book.

In middle school, with several classes to teach, I didn’t read aloud entire books, but I always shared essential scenes, passages, and chapters. Last year, for example, we read Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down, a novel in verse that has become one of my favorite books to read with my classes, one that I will always teach. I had the class read it on their own first, then I read aloud the essential ghostly elevator passages, in which each ghost imparts a message of some sort that may (or may not) influence the protagonist’s decision at the end of the book.

* * *

I have realized over the years that teachers — even English teachers — often don’t know much about children’s literature and often don’t venture far beyond the few books they teach each year. So how did I learn about children’s literature? I’m not a librarian. I didn’t study children’s literature anywhere, though Robin did: Jane Yolen and Patricia MacLachlan were her professors when she was an undergrad at Smith College. I was a history major and went to graduate school to study history. I taught myself about children’s literature. I read books and magazines about children’s literature. From the beginning, I read The Horn Book Magazine. I started going to conferences, beginning with Children’s Literature New England, where I met writers and illustrators to invite to speak at my school, many of whom became friends over the years. I found kindred spirits at these conferences, inspiring communities of librarians, teachers, reviewers, writers, illustrators, editors, and publicists. Robin and I always agreed that trips to conferences were a shot in the arm; we would return to school with renewed enthusiasm for our work.

We also quickly became more than attendees at conferences. We began serving on committees. I have now been on many, including Newbery, Caldecott, Sibert, Boston Globe–Horn Book, and, most recently, the Ezra Jack Keats Award Committee. This is where you really must up your game, because now your community — the committee — is a group of smart, dedicated, articulate professionals making important decisions.

Books and writing have always been the heart of my teaching. The kindergarten teacher would always introduce me this way: “This is Mr. Schneider. He’s the King of Books.” And I suppose that made more sense to five-year-olds than identifying me as head of the English department. So I became known as “The Bookman” around school over the years. I loved being the teacher who could get students reading. I had an excellent classroom library and gave students time in school to sit back and read. I could give enticing book talks to advertise good new books, or match a student who had just finished a book with the next good one.

I have loved working in a school where teachers can choose what books to teach and create their own lesson plans. I get to teach my own favorite books. In my previous seventh-grade classroom, I taught, among others, Lois Lowry’s The Giver, Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, Nancy Farmer’s The House of the Scorpion, Kekla Magoon’s The Rock and the River, Reynolds’s Look Both Ways, and Flying Lessons & Other Stories from We Need Diverse Books.

I have loved working in a school where teachers can choose what books to teach and create their own lesson plans. I get to teach my own favorite books. In my previous seventh-grade classroom, I taught, among others, Lois Lowry’s The Giver, Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, Nancy Farmer’s The House of the Scorpion, Kekla Magoon’s The Rock and the River, Reynolds’s Look Both Ways, and Flying Lessons & Other Stories from We Need Diverse Books.

I love creating literature units and thinking up connections to the books I teach. With The House of the Scorpion, we watched the old movie classics Dracula and Frankenstein and listened to Mozart’s “Turkish March,” the Adagio from Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 5, and Puccini’s “The Humming Chorus” from Madame Butterfly. I showed them Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam and read aloud Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit. What a rich curriculum a novel can suggest! Kwame Alexander’s excellent and funny short story in verse in Flying Lessons suggested a poetry-writing project, in which several of his poems were the models for students’ own writing, an easy way for literature to suggest creative writing.

I have moved to part-time teaching this year, so I go in for a shorter time each day to teach two eighth-grade classes. It’s November as I write this, and we have already read Jacqueline Woodson’s Miracle’s Boys and S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, and we’re approaching the end of To Kill a Mockingbird. Mockingbird makes for uncomfortable reading in the classroom because of racist language and the white savior figure of Atticus Finch. I might have skipped it this year if I hadn’t read Mildred Pitts Walter’s “‘Why Don’t You Write About White People?’” in the Horn Book (March/April 2022). Walter, a Black writer, said that white children need to read about characters like them “who will inspire them, answer their questions, and speak to their confusion, fears, and guilt about racism.” But I didn’t leave it at that as a justification for teaching To Kill a Mockingbird. I decided that if I was going to continue to teach it, I would match it with a current book on a similar theme by a Black writer. I chose John Lewis’s March: Book One, an apt selection for my school because much of the book is set in Nashville, and we can take advantage of the resources our city has to offer.

I have moved to part-time teaching this year, so I go in for a shorter time each day to teach two eighth-grade classes. It’s November as I write this, and we have already read Jacqueline Woodson’s Miracle’s Boys and S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, and we’re approaching the end of To Kill a Mockingbird. Mockingbird makes for uncomfortable reading in the classroom because of racist language and the white savior figure of Atticus Finch. I might have skipped it this year if I hadn’t read Mildred Pitts Walter’s “‘Why Don’t You Write About White People?’” in the Horn Book (March/April 2022). Walter, a Black writer, said that white children need to read about characters like them “who will inspire them, answer their questions, and speak to their confusion, fears, and guilt about racism.” But I didn’t leave it at that as a justification for teaching To Kill a Mockingbird. I decided that if I was going to continue to teach it, I would match it with a current book on a similar theme by a Black writer. I chose John Lewis’s March: Book One, an apt selection for my school because much of the book is set in Nashville, and we can take advantage of the resources our city has to offer.

My love of children’s literature has never wavered in forty-five years. I love teaching it and writing about it. And reading it, even as an adult. Katherine Rundell, in her wonderful treatise Why You Should Read Children’s Books, Even Though You Are So Old and Wise, writes that children’s books feed the imagination and that “it’s to children’s fiction that you turn if you want to feel awe and hunger and longing for justice: to make the old warhorse heart stamp again in its stall.” Katherine Paterson wrote in her essay collection The Invisible Child that “the book is almost the last refuge of reflection — the final outpost of wisdom.” This is the spirit of my work, where, through great literature, I encourage reading, writing, thinking, and imagining and try to reach that “outpost of wisdom” with my students — and remember to have a good time along the way.

So, after forty-five years, I, “The Bookman,” am still hanging in there, believing in the beauty and power of literature. I get to read books with kids for a living. How great is that! As former Horn Book editor Ethel Heins once said,

In this distracted, fragmented world, in order to offer the child the power of the literary experience, there must be connecting links between the child and the book — which is, of course, the knowledgeable, caring adult. And for you lucky few among us, I still believe that this remains our true calling.

From the March/April 2023 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Nancy Farmer

Dear Mr. Schneider,I was deeply moved by the way you taught my book, The House of the Scorpion. You noticed things even I didn't know was there -- The Creation of Adam is of course the transmission of a soul to what would otherwise be a beast. And you noticed the great importance of music. Frankly, the hair stood up on my arms when I wrote of the eejit children performing The Humming Chorus at El Patron's funeral. The book is moving swiftly towards a TV series, fortunately by people who really understand it and won't dumb it down. Thank you so much for putting so much care into teaching it. I really appreciate it.Nancy FarmerPosted : Apr 08, 2023 11:20