Confronting the Ovens: The Holocaust and Juvenile Fiction

by Eric A. Kimmel

When I was a child in Brooklyn there were several people in our neighborhood with numbers — small faint numbers neatly tattooed on the undersides of their wrists. We were not supposed to stare, but I can remember that even at an early age I could not tear my eyes away or keep from shuddering at the sight of those numbers. For those who bore them had been through the Läger — Auschwitz, Dachau, Majdanek, Chelmno — camps where people were murdered and burnt to ashes. Those little numbers, neatly inscribed and hyphenated, bore witness to horrors beyond my imagination.

The writer Elie Wiesel — who alone among his family friends, and neighbors passed through those camps alive and who writes of those unspeakable years with rare, midnight beauty — opens an essay entitled "My Teachers" with these words.

For some, literature is a bridge linking childhood to death. While the one gives rise to anguish, the other invites nostalgia. The deeper the nostalgia and the more complete the fear, the purer, the richer the word and the secret.

But for me writing is a matzeva, an invisible tombstone, erected to the memory of the dead unburied. Each word corresponds to a face, prayer, the one needing the other so as not to sink into oblivion. [Elie Wiesel, Legends of Our Time (Holt, 1968)]

Any writer dealing with the Holocaust is, like Wiesel, erecting a monument to the dead. Yet, if such a matzeva is to have any meaning, it must be a living memorial. It must justify their lives, dignify their deaths, and above all attempt, at least, to find some meaning behind the nightmare so that future generations will look upon it as more than a ghoulish carnival. For if the Holocaust remains incomprehensible, it will be forgotten. And if it is forgotten, it is certain to recur.

This terrible weight hangs especially heavy over the juvenile writer, who is torn between his duty toward his subject and his responsibility toward his craft: not to be too violent, too accusing, too depressing. Compounding the pressure is a realization reinforced almost daily, that most children — including many Jewish children — see cuddly, lovable Sergeant Schultz of Hogan's Heroes as a character far more real than Mengele, Höess, or Eichmann. Perhaps this is not surprising. Sergeant Schultz is far more comprehensible than the real Nazis, who were capable of enjoying, without a single pang of conscience, salads of prize vegetables fertilized with warm human ashes. If the dead are close at hand, oblivion is even closer. Yet how can we lay before the eyes of children scenes we can scarcely bear to look upon ourselves.

Children's books dealing with the Holocaust fall into a pattern similar to that of Dante's Inferno. The smoking chimneys of Birkenau are at the center with the lesser hells ringed around it in ascending order. The position of any one book on the spiral depends on what compromise is reached with the demands of subject, of audience, and of self.

The outermost ring consists of what might be termed Resistance novels. Though the individual setting might be occupied Denmark, Poland, or France, all such books essentially deal with young people taking an active role in the underground movements of their homelands. As such, saving Jews from the Gestapo often becomes just another respectable underground activity much like sabotage, posting placards, and smuggling arms and explosives. The Jews in these novels are seldom major characters but rather helpless unfortunates, threatened as much by their own inertia as by the Germans. They are completely incapable of coping effectively with their danger. Their reactions range from the stirring, if not especially practical, determination to hold a Rosh Hashanah service in Eva-Lis Wuorio's To Fight In Silence (Holt) to the total resignation of Mr. Jakoby in Bright Candles (Harper), who sits in his apartment waiting for the Gestapo to come.

If the Jews are marked by passivity, their rescuers often seem unable to grasp Nazi intentions. Vague references are made to concentration camps, but what goes on in such places is never really specified. To an extent this is excusable. The existence of the death camps was on the whole a fairly well-kept secret. However, in one book, Eva-Lis Wuorio's Code: Polonaise (Holt), the vagueness of the fate of the Jews is especially glaring. Code: Polonaise is set in Poland, yet it never mentions the Warsaw ghetto, the murder factories as distinguished from ordinary labor camps, or the virulent anti-Semitism of the Polish population — especially of the right-wing underground groups, were not above betraying fugitive Jews to the Germans or killing them themselves.

If the Jews are marked by passivity, their rescuers often seem unable to grasp Nazi intentions. Vague references are made to concentration camps, but what goes on in such places is never really specified. To an extent this is excusable. The existence of the death camps was on the whole a fairly well-kept secret. However, in one book, Eva-Lis Wuorio's Code: Polonaise (Holt), the vagueness of the fate of the Jews is especially glaring. Code: Polonaise is set in Poland, yet it never mentions the Warsaw ghetto, the murder factories as distinguished from ordinary labor camps, or the virulent anti-Semitism of the Polish population — especially of the right-wing underground groups, were not above betraying fugitive Jews to the Germans or killing them themselves.On the whole, however, there may be a reason for the blurred focus on the Jews in the Resistance novels. These book are above all optimistic: stories of young people struggling against great and terrible odds to win in the end. Besides, the outcome is hardly ever in doubt; Germany, after all, did lose the war. But so, to a considerable extent, did the Jews. And to face this unflinchingly is to inject an extremely somber tone into any work — far darker, perhaps, than anything these authors wish to convey.

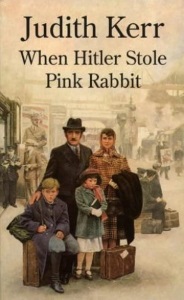

They cannot really be condemned for this. The authors of books in the next ring down are also reluctant to convey such a tone. The Refugee novels, written predominantly by Jewish authors, are either openly or admittedly autobiographical and deal with the experiences of families fleeing the Nazis. Concentrating on two books, Sonia Levitin's Journey to America (Atheneum) and Judith Kerr's When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (Coward), it is interesting to note that in many respects the pattern here is almost a mirror image of that of the Resistance novels. There, one of the most basic themes is the sudden changing of roles; schoolchildren, teachers, doctors, and housewives become soldiers, spies, and saboteurs. In the Refugee novels the transformation is equally abrupt. Highly cultured and affluent Jewish families discover overnight that the maniacs in power regard them as one and the same with the hook-nosed, Yiddish-speaking masses of Poland and Lithuania — all prey for the hunters. But in contrast to the helpless Jews of the Resistance novels, the families in the Refugee books are quite capable of coping with the crises they face. They plan and carry out their own escapes, meet the challenges of poverty and separation, and build new lives in foreign lands with courage, ingenuity, and great strength of character.

They cannot really be condemned for this. The authors of books in the next ring down are also reluctant to convey such a tone. The Refugee novels, written predominantly by Jewish authors, are either openly or admittedly autobiographical and deal with the experiences of families fleeing the Nazis. Concentrating on two books, Sonia Levitin's Journey to America (Atheneum) and Judith Kerr's When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (Coward), it is interesting to note that in many respects the pattern here is almost a mirror image of that of the Resistance novels. There, one of the most basic themes is the sudden changing of roles; schoolchildren, teachers, doctors, and housewives become soldiers, spies, and saboteurs. In the Refugee novels the transformation is equally abrupt. Highly cultured and affluent Jewish families discover overnight that the maniacs in power regard them as one and the same with the hook-nosed, Yiddish-speaking masses of Poland and Lithuania — all prey for the hunters. But in contrast to the helpless Jews of the Resistance novels, the families in the Refugee books are quite capable of coping with the crises they face. They plan and carry out their own escapes, meet the challenges of poverty and separation, and build new lives in foreign lands with courage, ingenuity, and great strength of character.However, though the families readily adjust to being refugees, they thoroughly fail to form any sense of a positive Jewish identity or commitment. In this sense When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit reaches heights of futility. Papa's definition of Jewishness is as follows:

"There are Jews scattered all over the world," he said, "and the Nazis are telling terrible lies about them. So it's very important for people like us to prove them wrong."

"How can we?" asked Max.

"By being better than other people," said Papa. "For instance, the Nazis say that Jews are dishonest. So it's not enough for us to be as honest as anyone else. We have to be more honest...We have to be more hard-working than other people...to prove that we're not lazy, more generous to prove that we're not mean, more polite to prove that we're not rude...It may seem like a lot to ask," said Papa, "but I think it's worth it because the Jews are wonderful people and it's rather splendid to be one."

In the next paragraph Anna effectively, but altogether unwittingly, reduces her father's statement to the absurdity it is.

Secretly she resolved really to wash her neck with soap each day while Mama was away so that at least the Nazis would not be able to say that Jews had dirty necks.

As if Goebbels cared what Jews did or didn't do. As for its being "splendid" to be a Jew, the real depth of the family's Jewish commitment is revealed later in Paris, when they go to great lengths to celebrate Christmas — complete with tree. It was families like this one, numbering in the thousands, who were the most pathetic victims of the Nazi program — unswervingly German in speech, dress, habit, and thought until a quirk of fate marked them with a yellow star.

The level of Jewish consciousness does not significantly change in the next circle. The books here are a varied lot that might best be called Occupation novels which, like the Resistance novels, are set in countries under Nazi control. However, unlike those in Resistance novels, the characters haven't the slightest connection with the underground. They are much closer in situation to the characters in the Refugee novels — alone, isolated, trying to survive as best they can, but not as well-to-do or as lucky.

The level of Jewish consciousness does not significantly change in the next circle. The books here are a varied lot that might best be called Occupation novels which, like the Resistance novels, are set in countries under Nazi control. However, unlike those in Resistance novels, the characters haven't the slightest connection with the underground. They are much closer in situation to the characters in the Refugee novels — alone, isolated, trying to survive as best they can, but not as well-to-do or as lucky.Of all the books in the circle, Hans Peter Richter's Friedrich (Holt) is the most harrowing. Richter, more than any other writer of juvenile fiction about the Holocaust, gives a menacing sense of the elaborately planned, systematic, and merciless unfolding of the Nazi persecution. Step by step the Jews, represented by Friedrich and his parents, are deprived of ordinary human dignity, a means of earning a living, property, police protection, and — when nothing is left — life. Friedrich, who was once a normal boy with many friends, dies alone in a bombing raid — a homeless, terrified creature, denied even the right to cringe in a corner of an air raid shelter.

In A Pocket Full of Seeds by Marilyn Sachs (Doubleday), the terror by contrast is quick and clean as a scalpel blade. The Nieman family, living in the hurricane's eye in occupied France, finds it hard to believe the danger they are really in. In spite of a growing awareness that many of his Jewish neighbors have already fled to Switzerland, Mr. Nieman decides to stay. He gets as far as the train station when he turns back.

...He put his suitcase down on the ground. "I'm not going. It doesn't make sense. And besides, we're making it all much worse than it really is. All those crazy stories! Who can believe them...A few more months and it will be over. You heard the BBC broadcast the other night. The Allies are already in Italy. For a few more months, why should I go? Nothing will happen in our town."

One gets the sense that Mr. Nieman is trying hard to convince himself that he is right. Crossing the border is dangerous; faced with the possibility of never seeing his family again, of being apart in such perilous times, he simply cannot go through with the attempt. Come what may, at least let his little family remain together. But he is wrong. His family is doomed. Unfortunately the Gestapo doesn't wait. When Nicole, the oldest daughter, comes home from spending the night with her friend Françoise, she finds the apartment ransacked and the family gone. The last chapters of A Pocket Full of Seeds form a bitter contrast to the Resistance novels, where everyone is ready and eager to help the Jews. Nicole, stunned and desperate for a place to hide, finds the doors of former neighbors and friends slammed in her face. It is Mlle. Legrand, a schoolmistress generally regarded as a collaborator, who finally takes her in.

One gets the sense that Mr. Nieman is trying hard to convince himself that he is right. Crossing the border is dangerous; faced with the possibility of never seeing his family again, of being apart in such perilous times, he simply cannot go through with the attempt. Come what may, at least let his little family remain together. But he is wrong. His family is doomed. Unfortunately the Gestapo doesn't wait. When Nicole, the oldest daughter, comes home from spending the night with her friend Françoise, she finds the apartment ransacked and the family gone. The last chapters of A Pocket Full of Seeds form a bitter contrast to the Resistance novels, where everyone is ready and eager to help the Jews. Nicole, stunned and desperate for a place to hide, finds the doors of former neighbors and friends slammed in her face. It is Mlle. Legrand, a schoolmistress generally regarded as a collaborator, who finally takes her in.Nicole's experience links A Pocket Full of Seeds with two especially important books whose theme is also going into hiding: Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl and Johanna Reiss's The Upstairs Room (Crowell). Because setting and action are limited to a small, restricted space — Anne's annex and the upstairs room of the Oosterveld house — these works emerge primarily as novels of character, masterful studies of human beings living under tremendous pressure. These people range from the phlegmatic, courageous Johan, Dientje, and Opoe to the glowing figure of Anne Frank herself, holding fast to love, beauty, and the hope for a better world in the nerve-grating tension of the rooms behind the bookcase. Anne Frank is not specifically a juvenile book. Yet the diary has so much to say to young people that we should have no hesitation in claiming it as one of the most meaningful children's classics. It is also the most vivid condemnation of the Nazi crimes in existence. For Anne, so sensitive and loving — who passed through the hell of Auschwitz to die in Bergen-Belsen — understood far more of life and was far more worthy of it than those faceless creatures who killed her.

The next ring down is the level of the heroic. This is the circle of Jewish resistance. As Milton Meltzer goes to great lengths to point out in his outstanding study, Never to Forget: The Jews of the Holocaust (Harper), there are two types of resistance. One is to take up gun and grenade and physically fight back. Another — equally heroic — is to go on living with decency and hope in the face of a monstrous regime oozing death and corruption. Thus the fighters of the forests and the ghettos, the Hasidim machine-gunned as they sang and danced, and those who simply endured are all worthy of praise.

The next ring down is the level of the heroic. This is the circle of Jewish resistance. As Milton Meltzer goes to great lengths to point out in his outstanding study, Never to Forget: The Jews of the Holocaust (Harper), there are two types of resistance. One is to take up gun and grenade and physically fight back. Another — equally heroic — is to go on living with decency and hope in the face of a monstrous regime oozing death and corruption. Thus the fighters of the forests and the ghettos, the Hasidim machine-gunned as they sang and danced, and those who simply endured are all worthy of praise.On this level there are three books reflecting the two types of resistance. What sets them off from the books previously discussed is that for the first time, we meet real Jews, standing together and not alone. Yiddish-speaking, sometimes religious and sometimes not, they are conscious and proud of their traditions. It's a striking contrast to those pathetic Germans, Hollanders, or Frenchmen who awoke one terrible day to find that the rest of the world considered them Hebrews. There are no Christmas trees here.

The first book is the magnificent Uncle Misha's Partisans (Four Winds). Yuri Suhl knows his subject well. He edited They Fought Back (Crown), the seminal book on the Jewish resistance. Based on the actual exploits of a real unit operating in the trackless forests of Russia, the story tells of the members of Uncle Misha's band fighting against the ruthless murderers of their families and friends. Uncle Misha's Partisans is one of the few books where Jews are not helpless, pathetic, frightened, or dependent on anyone or anything but their own courage and resourcefulness. Because they have transcended the desire to survive, they are no longer afraid to die. They have taken death from the hands of the Germans and given it a new meaning.

Resistance takes another form in Suhl's On the Other Side of the Gate (Watts). Hershel and Lena, a young couple trapped in a Polish ghetto, decide to have a baby. In any other time or place it would be a natural decision, but here it is a dangerous act and a highly symbolic one. Rations are at starvation level. The food and medicine needed by an infant are unobtainable. The Nazi authorities have forbidden Jewish women to become pregnant. And ultimately, what would be the fate of a child born into such a family at that time? Lena and Hershel have no illusions, and yet they persist. For by doing so they give the lie to all those who say that this is the last generation: There will be no more Jews. Long after their oppressors have sunk into the earth, the Jewish people will remain.

Resistance takes another form in Suhl's On the Other Side of the Gate (Watts). Hershel and Lena, a young couple trapped in a Polish ghetto, decide to have a baby. In any other time or place it would be a natural decision, but here it is a dangerous act and a highly symbolic one. Rations are at starvation level. The food and medicine needed by an infant are unobtainable. The Nazi authorities have forbidden Jewish women to become pregnant. And ultimately, what would be the fate of a child born into such a family at that time? Lena and Hershel have no illusions, and yet they persist. For by doing so they give the lie to all those who say that this is the last generation: There will be no more Jews. Long after their oppressors have sunk into the earth, the Jewish people will remain.And other Jews simply survive, as in Joseph Ziemian's The Cigarette Sellers of Three Crosses Square (Lerner), which is the true story of a ragtag band of urchins living by their wits on the Aryan side of Warsaw. Despite danger, hardship, and the lack of any specific ideology, they care for one another, share what little they have, and show far more humanity than those who persecute them.

The next circle brings us to the bottom, to the eerie, silent world of gas, ashes, and flames. Lower than this we cannot go, for this is the world of the camps. Only one book, Marietta Moskin's I Am Rosemarie (John Day), can be said to have descended this far, and even this book clings to the edges, not really daring to look fully on the central nightmare. For though Rosemarie and her family pass through the camps at Westerbork and Bergen-Belsen, surviving miserable food, disease, killing labor, and sadistic guards, they are comparatively fortunate. Their Latin American passports exempt them from the dread transports east, where thousands of Jews, herded by dogs and whips, are crammed into cattle cars and shipped to Poland to be "resettled." In the latter half of the book Rosemarie — seeing her dying friend Ruthie among the prisoners evacuated from Auschwitz when the Germans abandoned Poland to the Red Army — has the first inkling of what really happened in the eastern camps.

The next circle brings us to the bottom, to the eerie, silent world of gas, ashes, and flames. Lower than this we cannot go, for this is the world of the camps. Only one book, Marietta Moskin's I Am Rosemarie (John Day), can be said to have descended this far, and even this book clings to the edges, not really daring to look fully on the central nightmare. For though Rosemarie and her family pass through the camps at Westerbork and Bergen-Belsen, surviving miserable food, disease, killing labor, and sadistic guards, they are comparatively fortunate. Their Latin American passports exempt them from the dread transports east, where thousands of Jews, herded by dogs and whips, are crammed into cattle cars and shipped to Poland to be "resettled." In the latter half of the book Rosemarie — seeing her dying friend Ruthie among the prisoners evacuated from Auschwitz when the Germans abandoned Poland to the Red Army — has the first inkling of what really happened in the eastern camps.To date no juvenile book has as yet faced the ultimate tragedy in the manner of John Hersey's The Wall (Knopf), Andre Schwartz-Bart's Last of the Just (Atheneum), or Elie Wiesel's Night (Hill and Wang). This situation is due not to any dearth of able writers, but to the collision between the subject and some of our basic beliefs about the nature of literature for children and adolescents. To put it simply, is mass murder a subject for a children's novel?

Five years ago, we might have said no; ten years ago we certainly would have. Now, however, I think the appearance of a novel set in the center of the lowest circle is only a matter of time. Yet, what concerns me is whether or not that novel will come any closer to the question at the core of all this blood and pain. Can those millions of deaths be given significance to transcend the gross monstrosity of corpse-choked pits? Whatever the answer, we must never allow ourselves to forget the question.

From the February 1977 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!