Hitty Preble, Public Person

Hitty Preble — protagonist of the Newbery Medal–winning novel Hitty: Her First Hundred Years — is a doll with a history. Nothing is really known about her first hundred years, of course, but much has been written about her since. Her origin story was first told in the pages of the Horn Book in February 1930, in an article written by the book’s author, Rachel Field, called “How ‘Hitty’ Happened.”

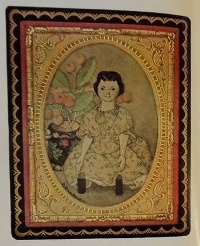

Hitty Preble — protagonist of the Newbery Medal–winning novel Hitty: Her First Hundred Years — is a doll with a history. Nothing is really known about her first hundred years, of course, but much has been written about her since. Her origin story was first told in the pages of the Horn Book in February 1930, in an article written by the book’s author, Rachel Field, called “How ‘Hitty’ Happened.” In it, Field describes having had dinner with artist Dorothy P. Lathrop two years earlier, and then walking down West 8th Street in NYC together. Lathrop suggested they stop by an antique shop to visit a six-and-a-half-inch-tall wooden doll she had seen there. As it happens, Field had frequently admired the same doll in the shop’s window. Her face was worn with age, and both women had been taken by her determined expression. The only real clue about her history was that the name “Hitty” had been written in old-fashioned handwriting on a piece of yellowed paper pinned to her dress.

Hitty Preble — protagonist of the Newbery Medal–winning novel Hitty: Her First Hundred Years — is a doll with a history. Nothing is really known about her first hundred years, of course, but much has been written about her since. Her origin story was first told in the pages of the Horn Book in February 1930, in an article written by the book’s author, Rachel Field, called “How ‘Hitty’ Happened.” In it, Field describes having had dinner with artist Dorothy P. Lathrop two years earlier, and then walking down West 8th Street in NYC together. Lathrop suggested they stop by an antique shop to visit a six-and-a-half-inch-tall wooden doll she had seen there. As it happens, Field had frequently admired the same doll in the shop’s window. Her face was worn with age, and both women had been taken by her determined expression. The only real clue about her history was that the name “Hitty” had been written in old-fashioned handwriting on a piece of yellowed paper pinned to her dress.

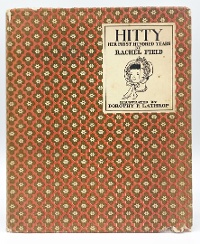

Field and Lathrop both felt inspired to create a history for the doll by writing and illustrating her “autobiography.” The doll, priced at twenty-five dollars, was expensive, but they pooled their money to buy it. Field would do the historical research and write the story, and Lathrop would illustrate it, using the doll as “the most patient of all the models I have ever had.” (Lathrop was famous for drawing animals from life, as she later did for her 1938 Caldecott Medal book, Animals of the Bible — the very first recipient of that award, in fact.) The two collaborated over the next year — sometimes getting together in person but more often exchanging letters, swapping ideas. It was a true collaboration. As the story began to take shape, their excitement about it grew, and resulted in Hitty: Her First Hundred Years, published by Macmillan in 1929.

Macmillan editor Louise Seaman Bechtel remembers the Hitty discovery a bit differently. In the manuscript of her unpublished autobiography, housed at the University of Florida, she recalls Field and Lathrop bursting into her office, telling her they had seen a doll in an antique shop and they could already envision the book they would create together about it. Would she buy the doll for them? Bechtel politely declined. The next time the two returned to her office, they were ready to talk about a contract for Hitty, and Field confidently declared that the book would be so good that it would be on the American Institute of Graphic Arts top fifty books of the year, would be a bestseller, and would win the Newbery Medal. Both Lathrop and Bechtel laughed at her. She turned out to be right on all counts.

From its first appearance, Hitty was a sensation. The Horn Book gave it a lot of ink in that February 1930 issue. In addition to Field’s article about how the book came to be, Lathrop wrote wryly about the challenges she faced as illustrator in “A Test of Hitty’s Pegs and Patience.” And there was a third article in the same issue about the doll’s appearance at the Bookshop for Boys and Girls in Boston (the site of the Horn Book’s own origin story) by Alice Barrett. “Hitty in the Bookshop” describes the reactions of her admirers, both children and adults, who came to the shop for a peek at the real Hitty, on display in a glass case. “Hitty had become a Public Person,” Barrett wrote. “As she sat complacently on her antique bench, her quill pen recently laid down, the ink still moist on the letter she had just finished writing, you could hear the thoughts whirring in her small head, ‘Yes, I am a wonder. I’ve surprised them once — and maybe I’ll do it again!’”

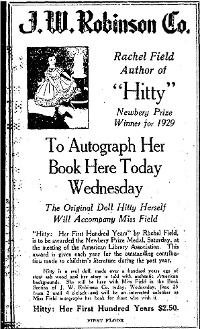

Ads for bookstore appearances; press coverage from the Los Angeles Times.

The Bookshop was just one stop in the first leg of Hitty’s American promotional tour. It had started at the New York Public Library, where she was the guest of honor at their Children’s Book Week celebration in November 1929. (No word on how she got on with Nicholas, Anne Carroll Moore’s infamous wooden doll. But, in the fall of 1929, Moore mentioned Hitty in her “Three Owls” column for the New York Herald Tribune no less than four times.) Hitty made public appearances up and down the East Coast, attended an “old dolls” convention in Cleveland, and was the guest of honor at a Christmas party at the Ritz in Boston. Everywhere she went, book sales followed. First printed in October of 1929, the book was reprinted twice in December, and again in May the following year, all before it had won the Newbery Medal.

In June 1930, Field took the train west to attend the American Library Association’s annual conference. She traveled as far as Clovis, New Mexico, where the local paper noted that the “well-known New York writer” had spent the night there, and then had boarded a T.A.T.-Maddux airliner bound for Los Angeles, 869 miles away. Why, you might ask, would Field get off a comfortable passenger train to get on a noisy and rickety plane for the last leg of what would have been a very long journey? The answer lies with Hitty.

In the final pages of Hitty, the doll, lying on her back in a shop window, watches an airplane fly overhead and muses that she might one day fly herself. It’s a literary nod to the future, suggesting that Hitty might have another hundred years of experiences awaiting her. We can’t be sure who first had the idea to grant her wish to fly, but we do know that Macmillan made the arrangements and paid for Field and Hitty to make the last part of the journey by air. By now, Hitty was enough of a celebrity that Bechtel had taken out an insurance policy on her.

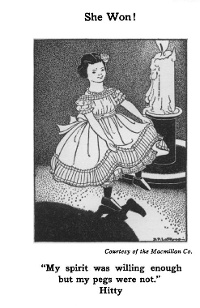

From the ALA Bulletin. Image courtesy of the American Library Association Archives.

In Los Angeles, librarians attending the ALA conference had just learned that Hitty had won the 1930 Newbery Medal, making Field the first woman to win the award. The otherwise sober ALA Bulletin reported the news with the headline “She won!” accompanied by one of Lathrop’s line drawings of Hitty dancing. “Imagine Hitty’s surprise when they told her that she was the winner of the John Newbery Medal!” the breathless report began. The enthusiasm for the book and author was so great that California State Librarian and ALA Council member Milton Ferguson and a group of children’s librarians (accompanied by the mayor of Los Angeles, according to Bechtel’s autobiography) boarded a second plane to fly toward Field’s plane so they could give her the Newbery news in the air. According to one of the local news reports, the pilot “swung abreast of the other plane, and after a wave of greeting from a window, Ferguson talked to the author over a plane-to-plane radio connection while they cut through the air for Los Angeles at more than 100 miles an hour.”

When Field and Hitty landed, there were more librarians on the ground, waiting to greet them, including Effie L. Power, head of the ALA Children’s Section and the 1930 Newbery chair. The press was there as well, and the story of Hitty’s flight to Los Angeles was widely covered in the national news. Photographs of Field deplaning with Hitty in tow often accompanied the articles. Macmillan had struck publicity gold.

Field, holding Hitty, posing in the cockpit after landing in Los Angeles (left);

an interview through the open plane window (right).

Photos courtesy of the American Library Association Archives.

After all this hoopla, the actual Newbery Award ceremony four days later may have seemed anticlimactic. In the medal presentation at the Biltmore Hotel, Power noted that Hitty had received first-place votes from all but one of the fifteen members of the Newbery committee. “We believe that Hitty is one of those ageless books, which will be read as long as there is any youth in the hearts of readers; that it is not only a book for boys and girls, but it is a book for all young people of whatever age between eight and eighty. While it is a story of a doll and perhaps primarily a book for girls, it is a book which boys are reading, and a book which boys will read because it is adventurous and because it rings true.” In her acceptance speech, Field recounted the story of how she and Lathrop found Hitty, paid tribute to Lathrop’s illustrations, and talked of the challenges she faced as a writer in bringing the doll to life. “I felt from the first that Hitty would have had a very prim but spicy way of talking, and so I tried to select every word and phrase carefully, for I think people don’t give words half enough credit. Yet they are what really affect readers, children most of all because they are most impressionable.”

Newspapers around the nation found a local angle on the story by reporting about their librarians who had attended ALA and had seen the doll in person. “Miss Edna M. Jarboe, librarian of Pocatello public library, attended the convention at Los Angeles where she met Hitty’s biographer, Miss Rachel Field and received an autographed copy of Hitty’s memoirs from her. She saw small Hitty in her glass house too,” reported the Pocatello (ID) Tribune.

After the conference, Field and Hitty once again hit the road, making appearances in bookstores and libraries throughout the western states. While on tour, one woman took Hitty’s measurements and made her a four-poster canopy bed, fitted with sheets, a pillow, and two handmade patchwork quilts, one of which was made by a ninety-year-old woman from one hundred and thirty tiny patches. Everywhere she went, Field autographed copies of the book for the crowds who came to see Hitty. By August the Matawan (NJ) Journal reported that Hitty had sold a million copies a month after winning the Medal.

Hitty-mania reached its peak in November 1930 when school and public libraries throughout the United States hosted doll conventions in her honor during Children’s Book Week. In early November, for example, the Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette put out a call: “Anyone having dolls to lend, especially old dolls since Hitty was a manikin of this type, is urged to bring them to the children’s department to be used in the display.” Newspapers described the dolls on display in libraries in great detail and reported the names of winners in categories such as oldest, biggest, smallest, best dressed, and best character doll. In one library, an imitation Hitty doll was judged “most popular.” But of course!

Original Hitty frontispiece. (c) 1929 by Macmillan Publishing Company. Copyright renewed in 1957 by Arthur S. Pederson.

After 1930 Hitty toured sporadically but spent most of her days in her bookcase apartment in Field’s home. She was surrounded by Hitty-sized furnishings that fans had sent her. Children’s interest in the doll continued, and in 1935 Field wrote an article for Child Life magazine about the bookcase apartments, which now housed other dolls as well. One of the photos accompanying the article showed Hitty making her bed, looking for all the world like a Dorothy Lathrop illustration come to life. Field kept the doll in her possession until she died unexpectedly at age forty-seven, just as her career as a novelist for adults had begun to take off. She won the very first National Book Award in 1935 for her novel Time out of Mind, and her book All This, and Heaven Too, was a bestseller and had just been made into a successful Hollywood movie starring Bette Davis.

Hitty was shipped to Lathrop after Field died (after all, they were joint owners of the doll), and eventually ended up in an estate sale after Lathrop died. Prior to the sale, however, an heir emerged to claim the doll. He understood Hitty’s historical significance and donated her to the Stockbridge (MA) Library Museum and Archives in 1988. She is there now, on permanent display in a little glass case for all admirers to see as she approaches the end of her second hundred years.

From the May/June 2022 special issue of The Horn Book Magazine: The Newbery Centennial.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!